Gender inequality, patriarchy skewed India’s sex ratio

Every minute one girl child is aborted somewhere in India, warns a recent study on the 'probabilistic projection of sex ratio at birth (SRB) in India between 2017 -30'.

Every minute one girl child is aborted somewhere in India, warns a recent study on the ‘probabilistic projection of sex ratio at birth (SRB) in India between 2017 -30’.

By 2030, a staggering 68 lakh sex-selective abortions (20 lakh in UP alone), are projected, says a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE by Fengqing Chao – of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Saudi Arabia, and her colleagues, Christophe Z. Guilmoto, Samir K. C, Hernando Ombao.

Unfortunately, the child sex ratio (CSR) i.e. the number of girls per 1000 boys in between 0-6 years of age has been declining since 1961. Due to widespread deliberate elimination of girls, the CSR was 945 in 1991 which got reduced to 927 in 2001. The plummeting CSR, dropping to just 918 in 2011, when the last nationwide census was undertaken, sparked renewed concern about the growing use of sex-selective abortions to satisfy obnoxious cultural preferences for sons.

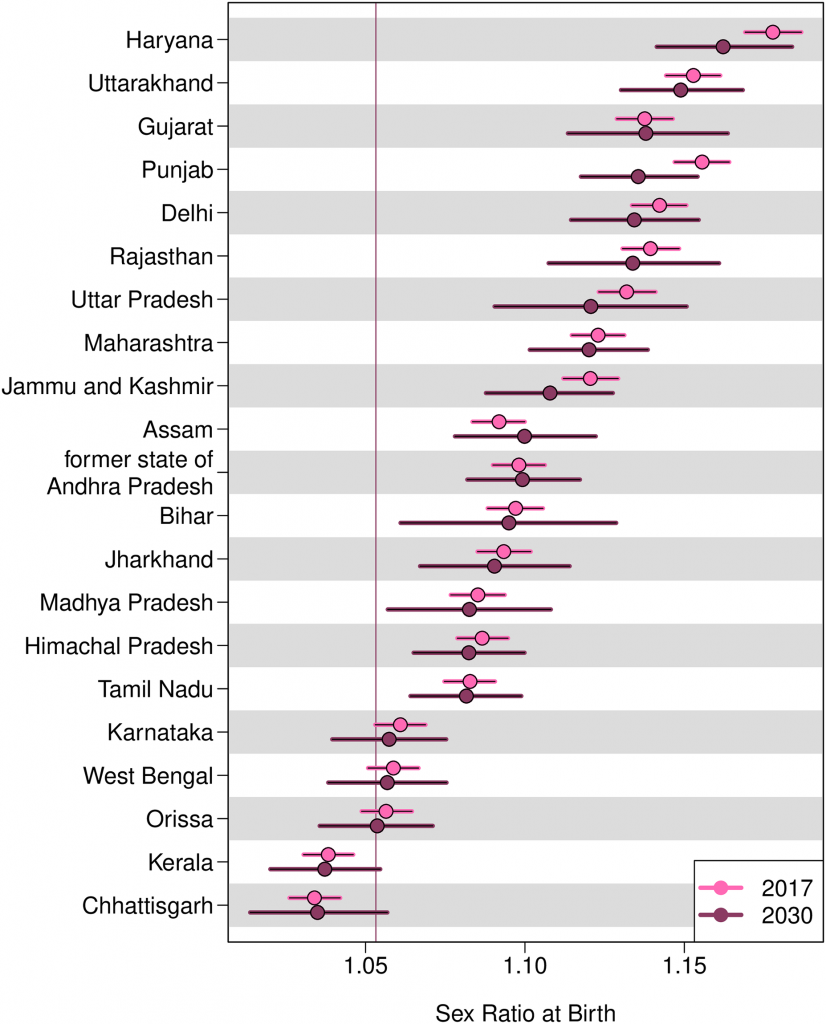

North-South divide visible

“India is unique in its regional diversity of SRB trajectories. Some states, such as Punjab, have experienced an early and rapid rise in birth masculinity since the 1980s. In contrast, in north Indian states, the masculinised SRB started to increase later. However, during the same period, many regions, most notably in south and east India, remained almost untouched by the emergence of prenatal sex selection seen in the rest of the country. Generally speaking, the highest SRBs are concentrated in most of the northwestern States/UTs, and lower in southern states and Chhattisgarh,” says Fengqing Chao, lead researcher.

“While ideal SRB suggested is less than 105 males for every 100 females (that is 1.05%), only the states of Chhattisgarh and Kerala are falling under this category for the period 2017-2030, going by this study findings. Odisha, West Bengal and Karnataka are little above the 1.05 range. Rest India are showing a trend of high sex ratio imbalance. Haryana, Uttarakhand and Gujarat are showing the highest levels of imbalance” says Raman VR, National Convenor, Public Health Resource Network.

Shortage of girls results in forced marriages, trafficking

With sex ratio nosedive to shocking levels in some areas of India, men are no longer able to find girls for marriage. Brides are ‘purchased’ from faraway places. This has also exacerbated forced marriages and trafficking.

Various patriarchal cultural factors contribute to male preference. While for some the onus of dowry makes a girl child a burden for others, the son preference may be related to the tradition of sons performing funeral rites. Sons carry on the family lineage, while daughters, after marriage, are understood to move away to become a member of another family. With most women shifting out to live with the husband’s house, old age care of the parents is usually provided by the son.

Related news: No shift in policy or want for girls make Tamil Nadu’s sex ratio stagnant

These ‘son preference’ cultural norms are age-old, yet the rise of the selective abortion during the 1980s is related to two factors. The promotion of small family norms since the 1960s paid off, resulting in a rapid decline in fertility. Each woman on average gave birth to a lesser number of children. As the ‘son preference’ social norm had to accommodate within a smaller family size, the girl child was seen as ‘unwanted’ and female foeticide became rampant.

Technology made sex determination easy

By 1980s the technology for sex determination and access to medical termination of pregnancy became commonplace. Amniocentesis, a technique used to determine whether a foetus has certain genetic disorders or a chromosomal abnormality, could also tell the sex of the child by 15- and 20-weeks’ gestation. A sonogram, commonly called as ‘scan’, can help monitor the fetus’ growth and position, confirm multiple pregnancies and guide other tests, such as amniocentesis. This very same technology can also tell the sex of the fetus.

Dr Vandana Prasad, a community pediatrician and public health professional and activists of People’s Health Movement-India (Jan Swasthya Abhiyan), says “as per the government protocol ultrasound scans are not part of its eight elements of Antenatal Care (ANC)”. Further, she says “scans are recommended to see if the foetus is growing normally and to detect congenital abnormalities if any. Scans also help to check if the placenta is at a normal position. Using the scan report, the gynecologist takes a view on the need of caesarean section for delivery of the child. However, there is no doubt the scans are widely misused for sex-selective abortions.”

While amniocentesis was technically demanding, expensive, the beta ultrasound is non-invasive and less technically demanding, could be performed at low cost. Moreover, in recent years, new methods of sex identification are available, which are at even affordable price, obtained over the internet, by 10th week of pregnancy. The market has adapted rapidly to what is an increasing demand, yielding significant profit to producers and providers of technology, however, at the cost of the girl child.

India, China and many Asian countries have outlawed prenatal sex determination. With increasing ex-pat Indian population, indulging in fetal sex determination and sex-selective abortion, a debate is raging in the USA to regulate the prenatal tests. However, the laws appear not to deter the practice of sex-selective abortions.

Related news: 30% girls from poor families in India never set foot in school: RTE

In an article published in Economic and Political Weekly in December 2000, Dr Sheela Rani Chunkath, former chief secretary, Government of Tamil Nadu and Dr Venkatesh Athreya, a former professor from Bharathidasan University, Trichy have documented a successful, large-scale effort of social mobilisation for gender equality using the communication strategy of street theatre, and involving the elected local bodies as well as people’s movements, along with the government in Dharmapuri district of Tamil Nadu in 1998-1999. These actions helped fight the practices of female infanticide and foeticide effectively. In subsequent years, the juvenile sex ratio (measured as the number of females per 1000 males in the age group of 0 to 6 years) has increased significantly throughout the district. “I must add that a single such effort is not enough. Son preference is deep-rooted in our patriarchal society. There has to be close monitoring at the community level of pregnancy outcomes and infant survival, and continued propagation of the necessity of moving towards gender equality,” said Dr Athreya, social activist.

South Korea scripts a success story

In this catch-22 situation, some feminists have called for outright ban on the prenatal tests and scans. Women’s right activists point out that without legal access to prenatal technologies and abortions, women are often forced to seek unsafe procedures sidestepping the regulated healthcare system.

A joint statement, ‘Preventing Gender-Biased Sex Selection: An Interagency Statement’, issued by OHCHR, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women and WHO in 2011 point out “States have an obligation to ensure that these injustices are addressed without exposing women to the risk of death or serious injury by denying them access to needed services such as safe abortion to the full extent of the law. Such an outcome would represent a further violation of their rights to life and health.”

Women empowerment is the gateway to setting right the sex-selective abortions and infanticide if one goes by the success story of South Korea. Like most of the Asian countries steeped in son preference culture, South Korea too saw declining girl child during the 1980s when the fertility ration dropped, and the technologies for sex detection became commonplace. In addition to a robust legal framework, more female employment in the labour market, laws and policies to improve gender equality and incessant campaign in the media helped the turnaround. Studies confirm that the normative changes in society rather than the changes in individuals due to improvement in socio-economic circumstances was the main reason for the reversal of the sex ratio at birth in South Korea.

India is changing too

Things are moving and shaking in the Indian social scenario too, giving hope for a better future. The appalling sex ratio in northern states like in Punjab, Haryana, Delhi and in Himachal Pradesh in the 2001 census was a wake-up call for many. Shocked by the figures, organisations like Himachal Gyan Vigyan Samiti got galvanised. They launched a state-wide Beti Bachao Andalon (save the girl child campaign) in 2003-2004. Five thousand grassroots level face to face interaction was conducted in villages and urban areas. “We build a state-wide platform of 28 organisations, which included various social movements, religious groups and political organisation. Educational campaigns were also organised, like during Navratri, when goddess Durga is worshipped. We did a campaign where we raised our voices saying people need girl child for pooja purpose, but they do not need them otherwise. These kinds of talks directly hit masses, and they reflected on it,” said Seema Chauhan, who was the coordinator for the joint platform of the Beti Bachao Andolan. The Andolan activists confronted the scan centres alleged sex determinations is carried out with mass demonstrations and urged the community to shun the overwhelming son preference. “In the modern world, we pointed out that a girl child is no less than a boy, in supporting the family at times of crisis or providing emotional support during distress”. Results of these campaigns were positive. The downward trend was arrested, and modest gains were made. “While the Andolan created the suitable environment, factors like the spread of female education, increased awareness among women about their rights, availability of employment and economic independence matters a lot,” says Seema Chauhan.

“Even with limited healthcare resources, the future abortion of girls in favour of male offspring can be minimised through better identification, monitoring, and education in the worst affected regions… Our study highlights the need to strengthen policies that advocate for gender equity and the introduction of support measures to counteract existing gender biases that adequately target each regional context” says Fengqing Chao.

Need a committed policy for gender equality

Dr Atherya concurs, “The present paper has raised very relevant and serious aspects of the highly masculine sex ratios at birth across the country, except for Kerala. A policy commitment to gender equality is essential. Systematic monitoring should also be done to enforce rules and laws to prevent heinous practices such as female foeticide and infanticide. Having said this, I would say that an approach based on law and order alone cannot ensure gender equality. We have to change the social norms too.”

Raman considers that the authors should have factored the access and use of technology for sex-selective abortion in India for better modelling. Further, he says they should have used the sex ratio for the last birth instead of desired sex ratio at birth. “While we may have nuanced criticism of the methods adopted and factored in the study, in the end, it may not drastically change the projection. In any case, the sex ratio situation in India, as depicted by the paper is worrisome. Most Indian states, except few, will continue with their son preference, and the ongoing abuse of imaging technologies as well as sex-selective termination of pregnancies” says Raman.

Reversing the abominable sex ratio at birth is linked to the broader social struggle for gender equity and dismantling of patriarchy. Enabling measures that provide access to education and health services to girls and women, laws that strengthen the gender equity in areas such as inheritance, employment and economic security and advocacy campaign involving various social forces to stimulate behaviour change regarding the value of girls, critical view towards the portrayal of girls as a burden in television serials are all necessary to arrest the alarming trend.