How Gandhi’s views on caste, race and God evolved through the years

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s views on the caste system changed in the last years of his life. In the 1920’s he had held that every Hindu “must follow the hereditary profession” (varnashrama) and that “prohibition of intermarriage” between people of different varnas was “necessary for the rapid evolution of the soul.”

By 1945, Gandhi’s position against the fourfold varna order had become more emphatic. He discarded some previous formulations, including those on hereditary occupations. In a new foreword to (new edition of) Varnavyavastha, he invited the reader “to discard anything in the book which may appear to him incompatible”.

The changes in the views of Mahatma Gandhi were arguably due to the influence of two opponents of the caste system whose intellectual integrity he held in high esteem – BR Ambedkar and Goparaju Ramachandra Rao (Gora). His view of marriage between people of different religious affiliations also underwent a similar change.

Regardless of the transition, his views have been criticised by various scholars. In an essay published in 2014, author and activist Arundhati Roy slammed Mahatma Gandhi for his “casteist tendencies” and defense of the varna system. Citing an essay by Gandhi in which he advises manual scavengers to convert urine and night soil into manure as proof of his condescending and patronising attitude towards Dalits and how such an attitude only helped reinforce caste hierarchies, Roy argued that institutions named after him be renamed.

Also read: The myth of a saint, legacy of a politician and appeal of a global inspiration

Documented evidence, including Gandhi’s own writings in the 1920s and ’30s, would indeed be considered casteist. But the documented fact also is that the latter-day Gandhi gradually became a social revolutionist advocating inter-caste marriage, especially between Brahmins and “Harijans” in order to dismantle the caste system “root and branch,” and publicly acknowledging that “when all become casteless, monopoly of occupations would go.”

Gandhi devoted much of his last years of his life-fighting caste as well as religious prejudice. He was a reformer and most definitely not a caste revivalist within the Hindu religion. His effort was in keeping with his philosophy of nonviolence and bringing societal transformation without creating animosity or hatred between groups.

The more important thing that we miss out when we try to selectively pick out his writings and claim that Gandhi was casteist is that, Gandhi strongly believed many times that he found himself in the wrong and therefore changed his mind, and most importantly that all his writings should be destroyed along with his body when it was cremated, because there was a risk that people would conform mistakenly to something he had written.

The constant criticism on Gandhi’s campaigns against untouchability by many a critic is that it would go only when caste was destroyed. It is not generally known that Gandhi moved to this position in the mid-1940s. It is also generally understood that while Gandhi opposed untouchability and criticised caste, he defended ‘varna vyavastha’, the fourfold varna order. This is not entirely correct over the entire Gandhian trajectory. Gandhi’s own criticism of the varna order, which evolved over time, has consistently and emphatically been overlooked by activists and scholars alike.

Gandhi and racism

Speaking at the at the Jaipur Literature Festival in 2018, Indian American writer Sujatha Gilda said that Gandhi was a “casteist and racist” who wanted to preserve the caste system and paid lip service to Dalit upliftment for political gain. The author recalled an episode from the political leader’s time in South Africa where he said “black” people were “kafirs” and “losers”.

“In Africa, when they were fighting against the British for instituting the passport… he said, ‘Indians are hardworking people, they should not be required to carry these things. But, black people are kafirs, losers and they are lazy, yes, they can carry their passport but why should we do that’?” she recounted at the fest.

This is the observation from Nelson Mandela on Gandhi in his earlier days in Africa. “During his imprisonment in Pretoria, all his fellow prisoners were Africans (Natives as they were then referred to, even by ourselves), and they, seeing him so different from them, were curious to know what he was doing in prison. Had he stolen, or dealt in liquor?

He explained that he had refused to carry a pass. They understood that perfectly well. “Quite right,” they said to him, “the white people are bad.” Gandhi had been initially shocked that Indians were classified with Natives in prison; his prejudices were quite obvious, but he was reacting not to “Natives”, but criminalized Natives.

Also read: Freedom and integration: A swaraj of the Mahatma’s dream

He believed that Indians should have been kept separately. However, there was an ambivalence in his attitude for he stated, “It was, however, as well that we were classed with the Natives. It was a welcome opportunity to see the treatment meted out to Natives, their conditions (of life in gaol), and their habits.”

All in all, Gandhi must be forgiven those prejudices and judged in the context of the time and the circumstances. We are looking here at the young Gandhi, still to become Mahatma, when he was without any human prejudice, save that in favour of truth and justice”

“The context of the time” used by Nelson Mandela is the operative word that seems to have been lost.

Gandhi and Atheism

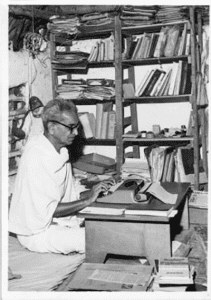

Goparaju Ramachandra Rao, known by his nick name Gora, was a big influence on Gandhi. Born in 1902 into an orthodox Telugu Brahmin family in Chhatrapur, Orissa (Madras Presidency), he was an atheist who campaigned aggressively against superstitions. He and his wife publicly viewed solar eclipses, as there was a superstitious belief that pregnant women should not do so. They stayed in a bungalow that was apparently believed to be haunted houses to dispel the myths about such places.

Gora used to run a monthly programme called “cosmopolitan dinners” every full moon night, where people of all castes and religions gathered together. Gora insisted on staying in a Dalit locality whenever he was invited to address a village. He also conducted several inter-caste and inter-religious marriages. His own sons and daughters married spouses from untouchable castes.

In 1933, he was dismissed from the PR College in Kakinada for being an atheist. In 1939, he was yet again terminated from Machilipatnam’s Hindu College for the same reason.

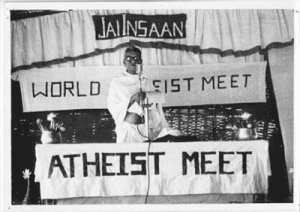

Gora believed both caste and religion have their epistemological roots in theism. So by practicing atheism, he strongly believed that he could possibly unite society. He had great respect for Gandhi (literally was a fanboy) and wanted to discuss his ideas with Gandhi. After multiple attempts (Gandhi was not inclined to meet Gora initially), he got to spend time with Gandhi at Sevagram.

Gora was in some ways a bridge between Gandhi and Ambedkar. Gandhi’s association with him was partly responsible for the change in his views on Ambedkar’s beliefs on the caste system. While Ambedkar was for the total annihilation of the caste system, Gandhi’s approach initially was milder; he wanted the negative aspects of the caste system like untouchability to go while retaining its philosophical frameworks. Gandhi came in contact with Gora late in his life, during 1944-45, following which Gandhi’ views on caste system saw a sea change, this has been documented by Mark Lindley, author of ‘The Life and Times of Gora’.

Gandhi was quick to question Gora on the issue of atheism, challenging Gora to differentiate between it and godlessness. Gora, not finding it new to have to defend his view, replied as follows: “Godlessness is negative. It merely denies the existence of God. Atheism is positive. It asserts the condition that results from the denial of God.”

Also read: Mahatma Gandhi to be health ambassador for children in new ICMR initiative

“Atheism bears a positive significance in the practice of life. Belief in God implies the subordination of man to the divine will. In the Hindu philosophical thought, man’s life is subordinated to karma or fate. In general, theism is the manifestation of the feeling of slavishness in man. Conversely, atheism is the manifestation of the feeling of freedom in man. Thus theism and atheism are opposite and they represent the opposite feelings, namely, dependence and independence respectively.”

Gora recalled the meeting later: “Bapuji listened to my long explanation patiently. Then he sat up in the bed and said slowly, “Yes, I see an ideal in your talk. I can neither say that my theism is right nor your atheism is wrong. We are seekers after truth. We change whenever we find ourselves in the wrong. I changed like that many times in my life. I see you are a worker. You are not a fanatic. You will change whenever you find yourself in the wrong. There is no harm as long as you are not fanatical. Whether you are in the right or I am in the right, results will prove. Then I may go your way or you may come my way, or both of us may go a third way. So go ahead with your work. I will help you, though your method is against mine.”

Regardless of the spiritual or religious label, the essence of every faith is the pursuit of a life of truth and goodness on earth. It is this broad-based view of life that Gandhi stood for; and hence time and again he had no hesitation in saying that he was a Hindu, a Muslim, a Sikh, a Christian and a Parsi.

Would he have called himself an atheist?

Since he adopted every creed based on the dharma of truth and goodness, it is quite likely that he would have believed in atheism too, provided this belief met the two criteria. After all, his entire life was devoted to the service of humanity. In 2019, he would probably have dismissed the debate over the creator—God or No-God— of humanity as a minor distraction.