Karnataka polls: 2023 verdict heralds seismic changes in state politics

While many pundits expected a hung assembly in the May 10 Karnataka elections, voters have delivered a decisive verdict. A resurgent Congress won 135 seats while BJP and JDS crashed to 66 and 19 seats, respectively. The three parties had respectively won 80, 104 and 37 seats in 2018.

The surge in the Congress seats was matched by a spike in its vote share, which shot up to 42.9% from 38.1% in 2018. But despite a steep fall in the seats, the vote share of BJP stayed near constant at 36% when compared to the previous elections. This created an initial impression that the party had managed to hold on to its vote bank, while anti-incumbency votes had consolidated behind Congress and helped it win new seats.

The bump in the Congress vote share stood out in contrast to a huge fall in the JDS vote share from 18.3% in 2018 to 13.3% in 2023. Many pundits said that the JDS loss translated into a Congress gain as Vokkaligas, the traditional supporters of JDS, shifted their loyalty.

Also read: Karnataka: Siddaramaiah, Shivakumar in Delhi to finalise Cabinet formation

This impression turns out to be erroneous and hides the momentous changes that have begun in Karnataka politics and the true extent of BJP and JDS loss. The election fractured hardened vote banks of parties and saw major shifts in voting preferences of different communities.

Region-wise shifts

Congress increased its share in all the six political regions of the state Kittur, Kalyana, Central, Coastal and Southern Karnataka, and the Bengaluru region. The JDS broke its back in the Vokkaliga belt in Southern Karnataka, its core support base.

The BJP lost a significant vote share in traditionally strong areas such as Kittur, Kalyana Central, and even Coastal Karnataka. It gained votes in Southern Karnataka and the Bengaluru region, which probably helped it maintain its overall percentage. But the new gains were not enough to bring it any new seat.

The new votes were not enough to translate into seats, but created an impression that its vote bank was intact. A quick look at the available data on how different communities voted shines light on the shifting fortunes of the different parties.

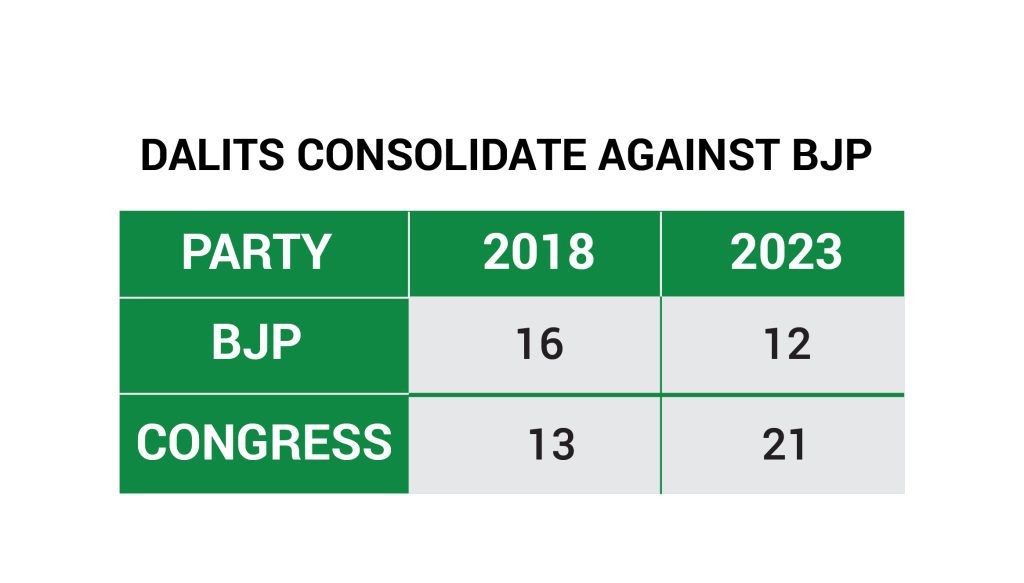

Dalits consolidate against BJP

This was a social group, which actively mobilised against the BJP, for almost two years. In the 36 reserved constituencies, BJP’s tally came down from 16 in 2018 to 12 in 2023. The Congress seats improved from 13 to 21.

Dalits are a bellwether of Karnataka politics. Their political mood sharply indicates the larger voter choice and BJP was clearly out of favour. With 17.5% of the population, Dalits are spread across and make an impact beyond the reserved constituencies as well.

In April, a source in RSS had claimed that BJP’s reservation strategy would fetch it Dalit votes. BJP proposed to increase reservation for scheduled castes from 15% to 17%. A few weeks before the election, it proposed to split the reservation internally between different Dalit groups to meet a longstanding demand of some of them.

The reservation move failed to deliver as Dalits believed that BJP lacked serious intention and was just playing for their votes. Internal reservation put off large communities like Lambanis and Bhovis, who were known supporters of BJP. A Lambani doctor reportedly gave a live chicken to every family in 12 Lambani villages near Bellary asking them to vote against BJP.

Also read: How Congress broke the deadlock over Karnataka leadership row

Structural shift in Dalits

The consolidation of Dalit votes against BJP may not be a passing phenomenon. Dalit groups have become wary that the BJP is out to undermine the Constitution and the privileges it guarantees for them.

Several groups came under the banner of Dalit Sangharsha Samithi (DSS) and held a huge convention in Bengaluru last December to resist the cultural aggression of the Sangh Parivar. In April they went to the Congress office and offered conditional support to the party. “We worked in the grassroots to mobilise Dalits against the BJP. The result shows,” says Indudara Honnapura, a prominent Dalit leader.

The 2023 seat share in reserved constituencies probably does not reveal the extent of Dalit anger against the BJP. A large section of Dalits, the ‘Left Hand’ castes, who have been agitating for internal reservation, may have cushioned its fall.

JDS, which usually wins a handful of these seats, drew a blank this time showing that anti-BJP votes had consolidated behind the Congress to avoid a split. This trend is visible in the way Muslims also voted in this election.

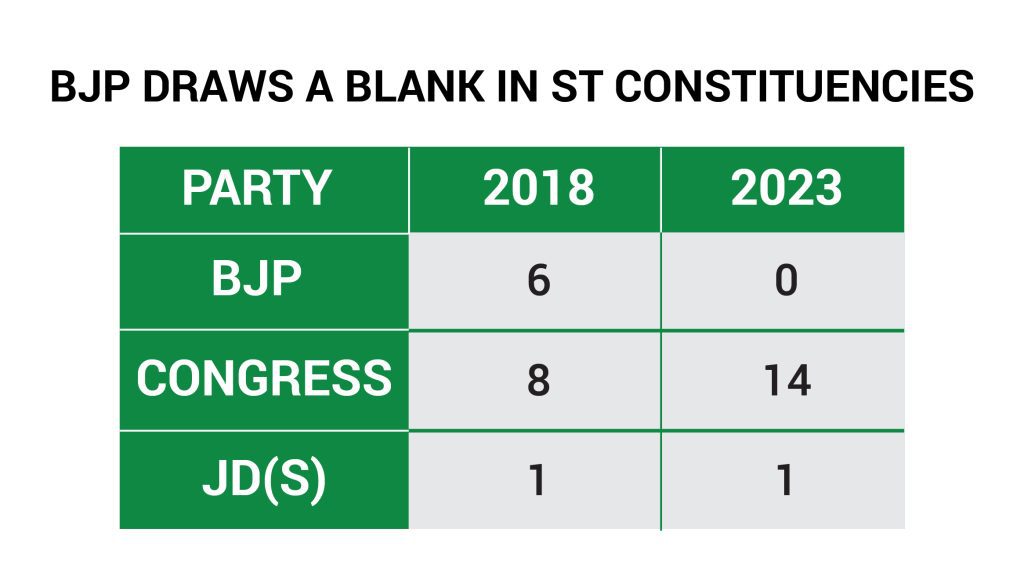

STs spring a surprise

In the 15 seats reserved for Scheduled Tribes (ST) BJP drew a blank. Congress won 14 and JDS got one. ST constituencies usually vote for different parties and in 2018 BJP had won six of these seats.

A few months ago there was consensus among pundits that STs were warming up to BJP, which had proposed to increase their reservation from 3% to 7%. Its decision to start observing ‘Valmiki Jananti’, the mythical founder of the Valmikis, the largest ST community, had touched an emotional chord. The most popular ST leader Sriramulu was seen as a rising star in the BJP.

The result came as a shock for the party, which was expected to sweep ST votes. A political science lecturer in Chitradurga said it is hard to explain why STs deserted their favourite party without notice. “They were probably influenced by the DSS campaign that BJP was against the Constitution. The anti-incumbency and waning fortune of Sriramulu in BJP may also have influenced them,” he says.

Also read: Had to bow down to Kharge, Gandhis: DKS on accepting Karnataka dy CM post

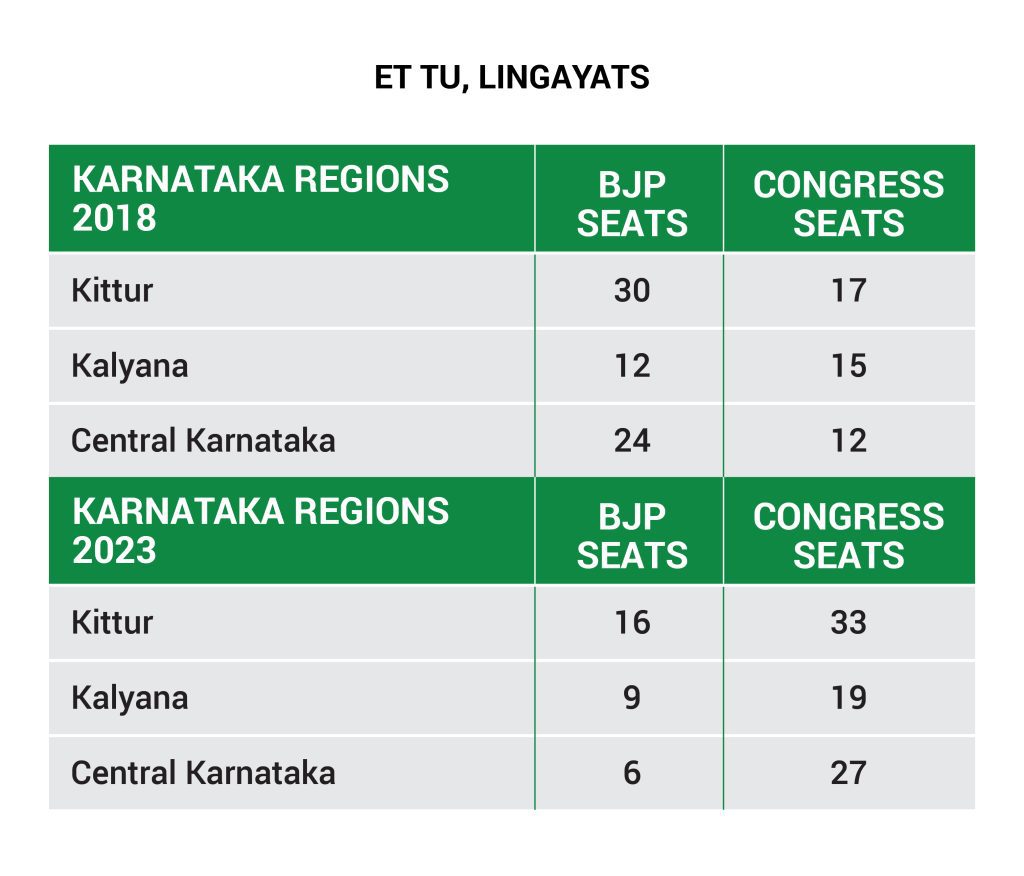

Et tu, Lingayats

Lingayats, who are about 15% of the population, were the force behind the BJP’s ascendance in Karnataka. Though they are spread across the state, their impact is particularly felt in Kittur, Kalyana and Central Karnataka, which emerged as BJP’s strongholds.

In these regions, BJP won 16, 9 and 6 seats respectively, a drop from 30, 12 and 24 in 2018. The Congress won 33, 19, 27 seats, a climb from 17, 15 and 12 seats in 2018. The combined vote share of BJP in these three regions came down by 5.6% and Congress’ share went up by 4.1%.

Lingayats had to overcome their antipathy to the Congress, which they see as a backward class party inimical to their interest, to punish BJP. Their strong support for BJP, routed through BS Yeddiyurappa, started cracking as the party began to sideline him. The denial of tickets to many prominent leaders like Jagadish Shettar and Laxman Savadi added to their discomfort.

After joining the Congress, Shettar targeted BJP/RSS leaders and successfully turned his grievance into a Lingayat vs Brahmin fight. While he lost heavily, his relentless attack deepened the anti-BJP narrative for Lingayats. Psephologist Sandip Shastry told a webinar on May 17 that at its peak the BJP enjoyed 60 to 65% of the Lingayat vote. “It has come down to 50 to 55% and Congress received 20 to 25% of their votes in this election,” he said.

A senior advocate, who ran the campaign of an independent candidate in Raibag, says up to 30% of Lingayat votes may have shifted from BJP to Congress in this election.

Also read: It’s official: Congress names Siddaramaiah as Karnataka CM; DK Shivakumar his deputy

Muslims vote en masse

Muslims, about 13% of the population in Karnataka, voted as a block to lift Congress across the state.

Professor Muzaffar Assadi of Mysore University said Muslims voted differently in this election and consolidated en masse behind the Congress. He estimates that 85% of the community votes may have gone for Congress, a trend which may add more clout to the community if it sustains.

Assadi says in the past Muslims have usually voted either for Congress or JDS assessing the winning chances of the candidate. In 2018, he observed Muslims voting for Congress, JDS and even BJP in North Karnataka. The central government schemes such as Ujwala and toilet construction drew especially Muslim women to BJP.

But during its four-year rule BJP went after Muslims relentlessly with incendiary speeches and a range of emotive issues, which peaked in the proposal to scrap the reservation for Muslims. “Fearing for their physical security, Muslims consolidated behind the Congress. Muslims vote for Siddaramiah not Congress as only he has stood up for them consistently,” Assadi says.

Muslims say they are not sure of JDS under HD Kumaraswamy (HDK) as there is always a chance of him joining hands with BJP. A strong evidence of their disconnect with JDS emerged in the Vokkaliga and Muslim dominated Ramanagara constituency, a HDK family borough. His wife gave up the safe seat to their son Nikhil, who lost to Iqbal Hussain, a Congress candidate, by 10,846 votes. As DK Shivakumar split the Vokkaliga votes, Muslims rallied behind Hussain and saw him home.

There are 9 Muslims MLAs in the new Assembly, up from 7 in 2018. All these MLAs are from the Congress, while all JDS Muslim candidates lost. BJP sticks to its policy of not giving tickets to Muslim candidates.

Watch | Spectacular Congress victory in Karnataka but high command has no control | Capital Beat

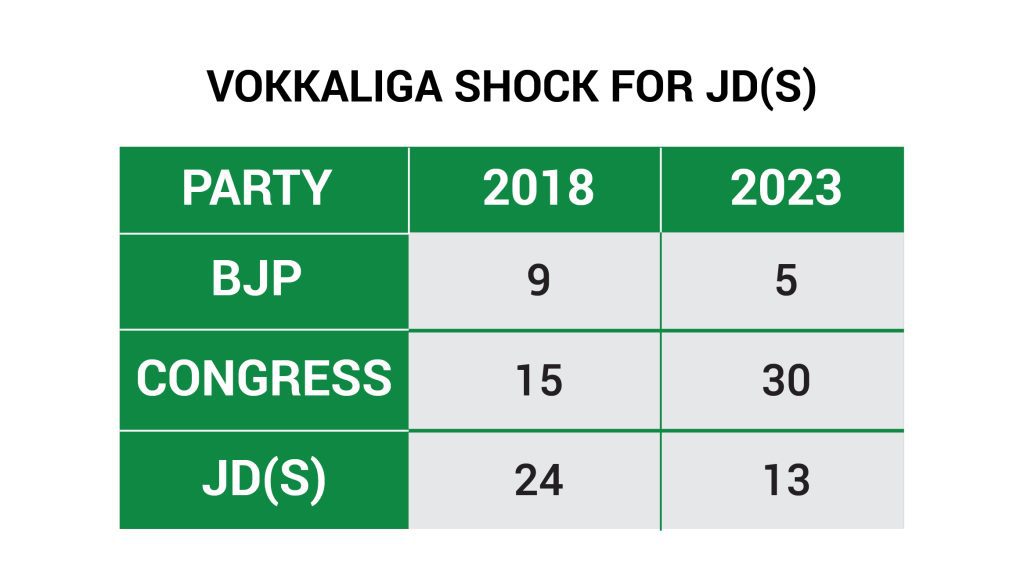

Vokkaligas dump JDS

JDS, which has enjoyed unflinching Vokkaliga support for long, imploded in this election. The party, a major political force in the Vokkaliga-dominated Southern Karnataka fell from 24 seats in 2018 to 13 seats. In a near reversal, the Congress tally in the region went from 15 seats in 2018 to 30.

BJP’s poor presence in the southern districts has stopped it from claiming a full majority in Karnataka. So to plug the lacuna, it sought to push into the region aggressively, pressing into service a real life Prime Minister Narendra Modi and two fictional historical characters, besides deploying its standard repertoire of tactics. All came to naught and BJP’s tally came down from 9 seats to 5. Though its vote share climbed from 18.2% to 21.4%.

The Congress ate into the JDS woes and increased its vote share to 39.4% from 33.8% in 2018. The JDS vote share in the region plunged from 37.4% to 28.6%.

JDS has probably paid the price for letting family claims gaining precedence over party affairs. Though it managed to sort out a long drawn family dispute over a seat in Hassan, the damage to public perception was done.

With BJP under Lingayats and the Congress backward classes, JDS was the only option for Vokkaligas. But with the rise of DK Shivakumar, Congress was able to promise a share in the power and became more attractive to them.

Their rivalry with Lingayats had also driven Vokkaligas to support JDS. As the Lingayats consolidated behind Yediyurappa after his dispute with HDK over sharing power in 2007, Vokkaligas felt obliged to rally behind JDS. But with Yediyurappa fading in the BJP and Lingayats moving away from the party they are also free to look at the other options.

Social groups such as Dalits and Muslims became so vehemently anti-BJP they seem to have concentrated their votes on Congress denying JDS its traditional vote share.

Also read: Karnataka: Outgoing CM Bommai leads the race to be opposition leader

Backward and upper castes

The voting in backward classes and upper castes was on expected lines. Anecdotal evidence suggests that upper castes such as Brahmins, who constitute less than 4% of the population, have stayed with the BJP.

Siddaramiah comes from the Kuruba caste, the third largest community in the state, which represents 8% of the population. Spread across the state, Kurubas were expected to overwhelmingly vote for the Congress and they did. Every election usually sends about 12 to 14 Kuruba MLAs to the Assembly. Media reports suggest that this time Congress sent 8 and BJP and JDS two each. The other backward castes in Karnataka are very small and BJP has been trying to mobilise them. Data needs to be compiled on how they have voted.

In sum, the 2023 election marks the beginning of a new phase in Karnataka politics. Over the last two decades, all the three parties had carved out distinct social bases, which has now been thrown into flux. Communities are telling parties that their votes have to be acquired and not taken for granted. They are showing more awareness of their self-interest and a readiness to negotiate, forcing parties to reboot their ideology and strategy.