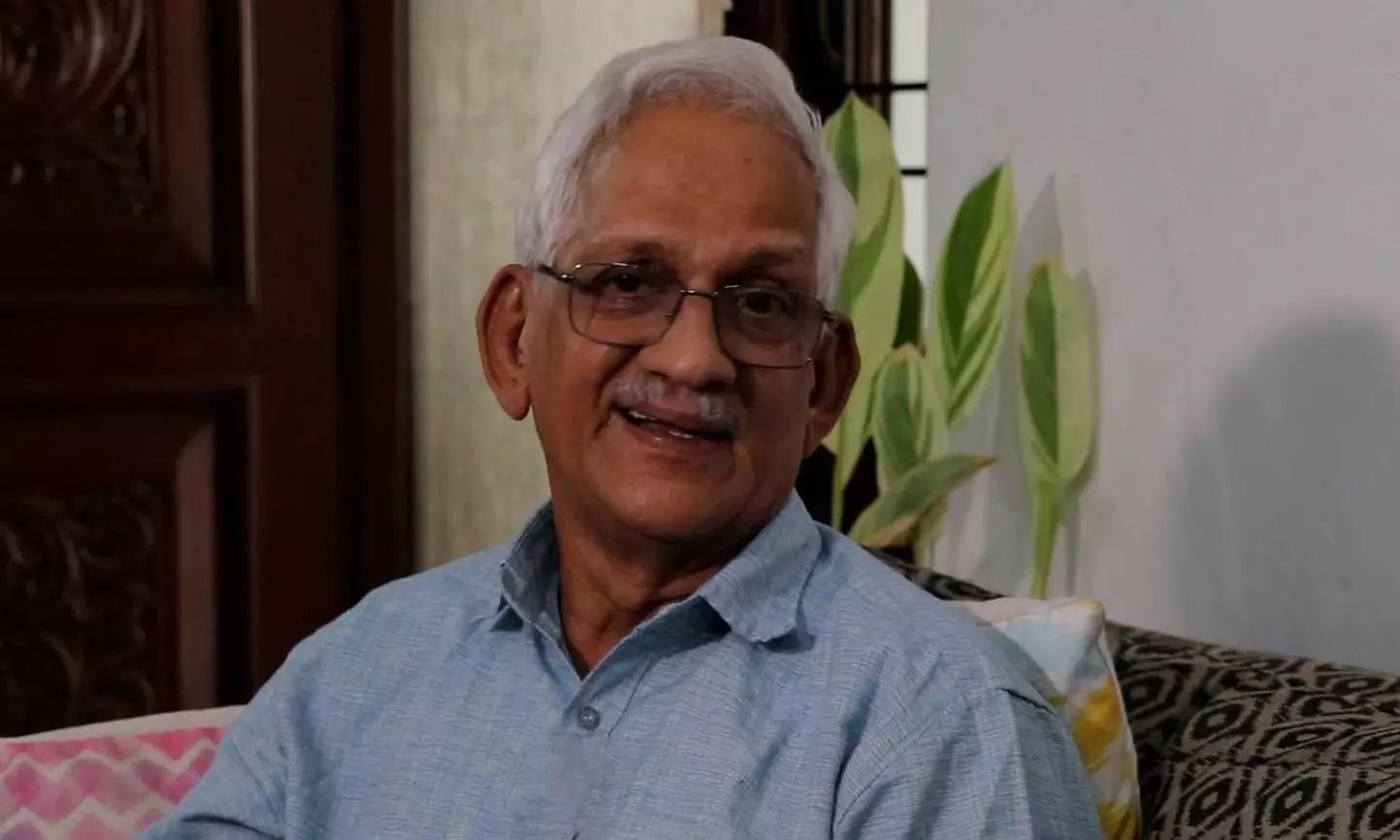

2 things that are grossly wrong with GST: Economist Venkatesh Athreya exclusive

He says GST undermines states' fiscal autonomy; also, a tax regime constituting 65 pc of total mop-up doesn't distinguish between rich and poor, which is problematic

As India marks eight years since the rollout of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) on July 1, 2017, debates continue over the tax reform’s effectiveness, fairness, and structural design.

Promoted as a landmark step towards simplifying the tax system and fostering cooperative federalism, GST was hailed as a transformative move for the Indian economy. However, its performance has been met with mixed reactions from economists, policymakers, and the public alike.

In an interview with The Federal, noted economist Venkatesh Athreya delivered a sharp critique of the GST regime. Contrary to the government's narrative of unity and ease, Athreya contended that GST has instead centralised fiscal power, diminishing the autonomy of state governments and consolidating control under the Union government.

This centralisation, he argued, disproportionately benefits corporate interests at the expense of states and the poorer sections of society. Edited excerpts:

One of the biggest criticisms of GST has been its complexity. Too many slabs, exemptions and frequent rate changes. Has GST failed to deliver the simplicity it promised?

It depends entirely on whom you're looking at. For the poor, GST has dealt a body blow. It’s an atrocious form of taxation—an indirect tax that makes no distinction between rich and poor. At its core, GST suffers from two fundamental problems. First, it undermines the fiscal autonomy of state governments. Earlier, states could levy their own indirect taxes. Under GST, they’ve lost that power.

Everything must now go through the GST Council, where the Union government holds disproportionate sway. This centralising design serves the interests of big corporates, who prefer a “single market” with uniform rules — and little regard for state governments. What we’ve seen is a serious erosion of federalism.

Also read: GST, a landmark reform that reshaped India's economic landscape: PM Modi

The grand spectacle of GST’s launch in 2017— touted as a “second Independence Day”— was in fact a moment where centralisation deepened under the guise of reform.

Second, GST being an indirect tax makes it fundamentally regressive. It doesn’t factor in the ability to pay. The rich and poor pay the same rate for the same goods. This is deeply unjust. Direct taxes, like income tax, are meant to be progressive. But even those have been diluted over time by exemptions and loopholes for the wealthy.

Today, nearly 65 per cent of India’s tax revenue comes from indirect taxes. That’s a damning indictment of our tax structure.

Revenue collections are now stronger than ever. We had a PIB press release stating that gross GST collections doubled in five years to hit record ₹22.08 lakh crore in FY25. But is that success covering up deeper issues such as uneven state-level compliance and enforcement gaps?

Yes, GST revenues have doubled to ₹22.08 lakh crore in five years. But we must ask: where is this money coming from? Not from corporate boardrooms, but from 1.4 billion people, most of whom are poor or lower-middle class. The government celebrates these record collections, but fails to ask tough questions about direct tax performance.

The total tax-to-GDP ratio in India has barely crossed 15–16 per cent. That’s exceptionally low for a country with such stark inequality.

The top 1 per cent owns 42 per cent of the country’s wealth. But we’ve abolished the wealth tax, citing poor collections. Instead of fixing loopholes, the government simply removed the tax. This is not tax reform—it’s capitulation to the elite.

Corporate tax rates have been slashed repeatedly, while personal income tax relief for the middle class remains modest.

Also read: Gross GST collections double in 5 years to hit Rs 22 lakh-cr in FY25

So, when we measure GST’s success, we must ask: Is higher revenue the only metric? Or should we also consider who is bearing the burden?

GST has severely limited states’ ability to make fiscal decisions. They now independently tax only four commodities: petrol, diesel, alcohol, and tobacco. This is deeply problematic, as elected state governments are now unable to raise revenue for their own developmental priorities.

The imbalance is stark. States bear the bulk of welfare responsibilities, yet collect a fraction of the revenue. This has forced the Finance Commission to provide revenue deficit grants, acknowledging the structural flaw. Even basic taxation principles—such as taxing luxury goods at higher rates—have been diluted or resisted under pressure from corporates.

Remember, sanitary napkins were taxed at 18 per cent at one point, in a country where we run campaigns like “Beti Bachao.” Bureaucrats focused only on raising revenues, with little consideration for the social impact.

Destination-based taxation has hit manufacturing-heavy states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. Should there have been a more equitable formula to balance producing and consuming states?

Yes, manufacturing-heavy states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have been hurt under the destination-based model of GST. But the issue is larger than just “producing vs consuming” states.

Also read: Govt notifies rules for GST appellate tribunals; provides for e-filing, hybrid hearing

The bigger problem is the centralization of financial power, with little regard for regional needs or diversity. In countries like the US or even China, states or provinces enjoy much more fiscal freedom. In India, states have become dependent on the Centre, which undermines accountability and governance at the grassroots level. People vote for state governments expecting them to deliver—yet these governments often don’t control their own purse strings.

A modified GST regime must restore some taxation powers to states, introduce greater rate stability, and most importantly, rethink the share of revenues between Centre and states.

Has the GST Council truly functioned as a platform of cooperative federalism or has it gradually tilted towards central dominance, especially in terms of agenda-setting and decision-making?

The GST Council was pitched as a forum for cooperative federalism, but in reality, it reflects central dominance. The Centre often sets the agenda and dominates decision-making. Even in areas like education or healthcare, states that refuse to toe the line are threatened with funding cuts. So yes, the rhetoric of “cooperative federalism” is strong—but the practice is coercive.

States are treated less as equal partners and more as administrative units of the Centre. Moreover, the push for uniformity—in taxation, in education policy, in language—comes at the cost of India’s diversity. Corporates love uniformity because it simplifies compliance. But for a country as diverse as India, diversity in policy-making is a strength, not a weakness.

GST must be restructured to restore some degree of fiscal autonomy to states, especially over items relevant to their economies.

If you were to rewrite the GST today, what’s the single biggest design flaw you would correct and what’s the most important reform we must prioritise next?

The single biggest design flaw I would fix is the erosion of state taxation powers. GST must be restructured to restore some degree of fiscal autonomy to states, especially over items relevant to their economies. More broadly, I would reform the Centre–state fiscal relations. The current devolution formula (41 per cent of the divisible pool to states) must be revised upward—at least to 50 per cent.

States have far more responsibilities than the Centre and need commensurate resources. As for GST itself, yes, we must aim for simplification, but not at the cost of equity. We can have 2–3 tax slabs, with luxury goods taxed higher. We should raise exemption thresholds for small businesses and make compliance easier, so that small traders aren't crushed under bureaucracy.

Finally, a national conference involving all states, economists, and civil society should be convened to re-examine GST—not just to raise revenue, but to make the tax system fairer, more transparent, and more people-centric.