Bihar Assembly election: Will exit polls get it right? What does record turnout imply?

This episode of Capital Beat decodes voter turnout trends, exit polls, and the evolving political equations between NDA, Grand Alliance, and Jan Suraaj Party

As the final phase of polling concluded in Bihar, political observers and journalists, including Anand K Sahay, Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, Prof. Sanjay Kumar, and Puneet Nicholas Yadav joined The Federal’s Capital Beat to decode voter turnout trends, exit poll findings, and the evolving political equations between the NDA, Mahagathbandhan, and Jan Suraaj Party.

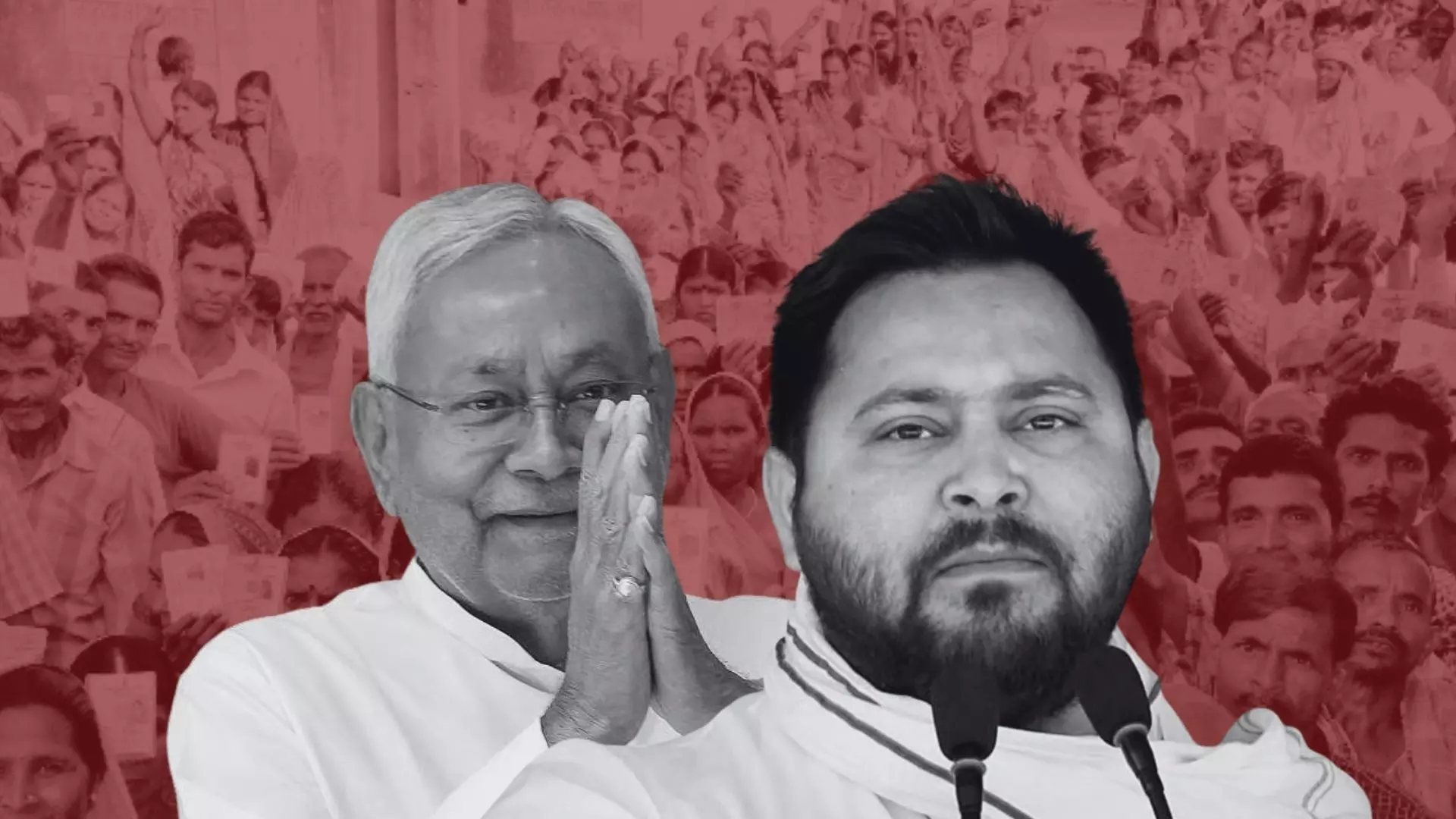

The discussion examined the credibility of exit polls, the implications of a record turnout exceeding 65 per cent, and what the numbers could mean for Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, Tejashwi Yadav, and Prashant Kishor’s debutant Jan Suraaj Party.

Exit polls questioned

Sahay expressed strong scepticism about exit polls, saying they “often get it wrong” and lack scientific consistency. “The very same companies that conduct these polls are the ones that dominate prime-time debates. If they get it right, it’s a fluke,” he said, recalling that similar agencies had made incorrect predictions in past elections, including the 2004 and 2009 Lok Sabha polls.

Sahay cautioned against reading too much into the preliminary results, many of which showed the NDA ahead. “All the polls are moving in one direction, but the methods remain questionable,” he noted, arguing that the process lacked transparency and could be agenda-driven.

Also read: Exit polls in charts: NDA has clear edge in Bihar elections

Mukhopadhyay supported this view, raising concerns over the credibility of polling agencies. “Several of these firms are unknown entities. Some have no record of conducting major surveys in the past,” he said. He added that the speed with which exit polls are released also compromises their accuracy. “When voting ends at 6 pm, how can there be authentic surveys by that time?”

Turnout and credibility

Prof. Sanjay Kumar offered a data-driven counterpoint, noting that high turnout figures — particularly in Seemanchal’s Muslim-dominated districts — indicated a close contest. “By 5 pm, the voting percentage was 67.5. In Seemanchal, it touched 70 per cent,” he said. Based on voting patterns, he predicted the possibility of a hung assembly but suggested the Mahagathbandhan had performed strongly in the second phase.

Puneet Nicholas Yadav, reporting from the ground, confirmed the unexpectedly high voter participation across Bihar. “In districts like Kishanganj and Araria, turnout exceeded 60 per cent by 3 pm,” he said. He observed that Seemanchal appeared to favour the Grand Alliance this time, while other areas traditionally supportive of the NDA showed comparatively lower participation.

Yadav noted, however, that despite large turnouts, the overall contest remained close. “It wasn’t a one-sided election as the exit polls suggest. On the ground, it was much tighter — similar to 2020,” he said.

High turnout, mixed signals

The panellists explored whether Bihar’s record turnout could influence results. Sahay referenced historical trends where voter participation above 60 per cent had favoured the Opposition, recalling that “anything above 60 used to mean Lalu Prasad’s victory”. However, he cautioned that electoral manipulation, deletions from voter rolls, and EVM concerns added uncertainty to the equation.

Also read: 'Paltu Ram' tag aside, Nitish still electoral linchpin, but will he be CM again?

Prof. Kumar pointed to the controversy over deleted voter names, echoing concerns raised by the Opposition. “About 76 lakh names were deleted and 20 lakh added, so nearly 50 lakh voters were cut off,” he said. Despite that, overall turnout rose, which he found “beyond understanding.” He suggested that migrant voters returning for Chhath Puja and Prashant Kishor’s long campaign could also have contributed to the rise.

Women voters and Nitish’s appeal

The discussion turned to the perception that increased female turnout might benefit Nitish Kumar. Sahay said the belief stemmed from the 2016 prohibition policy that initially won him strong support from women. “It gave relief from domestic violence and wasteful spending,” he said, but added that illegal liquor trade had since undone much of that goodwill.

Citing Election Commission data, he said the NDA’s women vote share in 2020 was only one per cent higher than that of the Opposition. “So it’s hard to say if there’s been a massive surge in support,” he noted. He also referred to activist Shabnam Hashmi’s survey of 6,500 women across 20 districts, which found that while women appreciated cash transfers, most were struggling under mounting microfinance debt.

BJP’s strategy and limitations

Mukhopadhyay assessed the BJP’s positioning in this election. While the party had campaigned on the “Jungle Raj” theme, he argued that it had lost relevance among younger voters. “For today’s 20–30-year-olds, Jungle Raj means nothing — it’s just a phrase inherited from their parents,” he said.

Also read: Bihar election: Why Seemanchal's political landscape appears set to change

He noted that despite the BJP’s attempts to project itself as the driver of development, the definition of progress remained narrow. “Development has come to mean highways. Beyond Patna, the picture changes drastically,” he observed, adding that infrastructure expansion had not translated into jobs.

On Hindutva politics, Mukhopadhyay said the BJP’s “ghuspetiya” (illegal infiltrator) narrative had little traction in Bihar, unlike in parts of Uttar Pradesh. “It failed in Jharkhand, and there’s no evidence it will succeed in Bihar,” he said, pointing out that Nitish Kumar has never endorsed Hindutva politics and continues to maintain his minority outreach.

Congress, Tejashwi, and campaign dynamics

Yadav remarked that the Congress campaign began with enthusiasm but lost steam midway. “Rahul Gandhi’s rallies drew large crowds, but state-level leadership couldn’t sustain the momentum,” he said, attributing it to weak organization and factionalism.

On Tejashwi Yadav’s performance, he noted both strengths and missteps. “He’s come into his own as a leader but made avoidable errors,” Yadav said, citing instances where Tejashwi skipped rallies due to rain while Nitish continued campaigning. “That sent the wrong message,” he added. Internal rivalries, including fielding a candidate against his brother Tej Pratap, also hurt his image.

The third front and caste equations

Discussing Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party, Sahay acknowledged Kishor’s articulate campaigning but said his caste background might limit reach. “He takes up the right issues but lacks a strong social base,” he said. Mukhopadhyay added that Kishor’s rise was largely “a media creation” but conceded that continued consistency could make him a serious contender in future elections.

Also read: Why the 2025 Bihar Assembly election matters for all of India

Yadav concluded with an overview of caste arithmetic, noting that both alliances focused heavily on social engineering. “The RJD and Congress chased upper-caste votes, while Nitish Kumar’s JDU maintained a balanced caste mix,” he said. “However, friction within alliances, including LJP-JDU tensions, affected cohesion on both sides.”

(The content above has been transcribed from video using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.)