How Ramana Maharshi’s philosophy kept the Father of Green Revolution grounded

New biography by Priyambada Jayakumar reveals how MS Swaminathan drew inner balance and ethical clarity from the teachings of the sage of Arunachala

When author Priyambada Jayakumar began researching The Man Who Fed India, her biography of MS Swaminathan, she thought she knew his story — the scientist who steered India out of famine through the Green Revolution. What she found instead was a man whose ideas on food security were as much shaped by spiritual discipline as by agricultural science.

Book excerpt | How MS Swaminathan’s collaboration with Norman Borlaug engineered the Green Revolution

Swaminathan, who died in 2023 at 98, is credited with transforming India from a grain importer to a food-secure nation. His hybrid of science, policy, and diplomacy earned him the Bharat Ratna and global recognition.

Yet, as Jayakumar notes, his intellectual roots went beyond laboratories and policy tables.

The silence behind science

“He had a quiet fascination for Ramana Maharshi, the sage of Arunachala who taught self-realisation through silence,” she says. “That contrast intrigued me. Here was a man dealing daily with data, genetics and policy, yet drawn to the stillness of a mystic.”

For Jayakumar, that paradox explains part of Swaminathan’s method. “Our anchors are often the antithesis of who we are,” she says. “His world was noise, pressure and politics, but he drew equilibrium from silence.”

MS Swaminathan saw genetic technology as a knife. It can cut food, or it can kill. Technology itself isn’t moral or immoral — its use is.

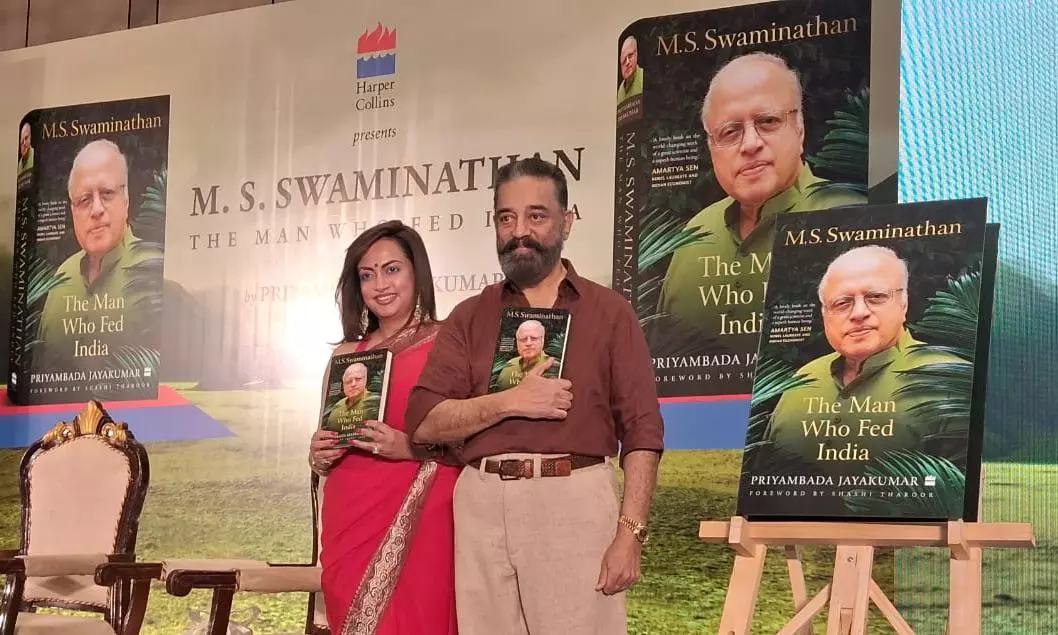

The biography, launched in Chennai on November 2, is the first to probe that interior world. Earlier works focused on Swaminathan’s scientific achievements — the high-yield seeds, the public-sector push, and the transformation of Punjab’s farmlands. Jayakumar’s book instead examines the person behind the reformer: his values, marriage, and moral vocabulary.

Watch | To make farming viable, follow MS Swaminathan’s recommendation: Agri scientist

“This isn’t a technical book,” she clarifies. “It’s about what made him the kind of scientist he became.”

Among her more striking findings is a forgotten detail from his student years — Swaminathan was present at Birla House in Delhi on the day Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated, attending the same prayer meeting. “That small moment placed him directly in the moral current of India’s freedom generation,” she says.

Science with a conscience

The moral thread runs through the book, starting with Swaminathan’s father, a physician in Kumbakonam, who often said: “For every malady, there is a remedy – if you have the compassion to look for it.”

That early lesson in persistence and empathy shaped the scientist’s later philosophy – that science without social purpose was hollow.

His admiration for Ramana Maharshi wasn’t incidental; it symbolised his belief that inner clarity was as crucial to discovery as external inquiry.

Swaminathan’s approach to biotechnology mirrored that ethic. “He saw genetic technology as a knife,” Jayakumar says. “It can cut food, or it can kill. Technology itself isn’t moral or immoral — its use is.” His nuanced stance on genetically modified crops stands in contrast to today’s polarised debate between pro-GM lobbyists and anti-science activists.

Also read | MS Swaminathan obituary: The genius who made India food secure

The book also revisits his overlooked work on women in agriculture. “Ask anyone to picture a farmer — they’ll describe a man,” she says. “But most of the planting, threshing and weeding in India is done by women. He argued for credit, land titles and institutional recognition for women farmers long before gender equity became policy jargon.”

That gender sensitivity, she notes, came partly from his marriage to Mina Swaminathan, an educationist. “He wouldn’t have been who he was without her,” Jayakumar says. “She was his intellectual counterpart and moral compass.”

Seeds of lasting change

If the Green Revolution made India food-secure, Swaminathan’s later call for an ‘Evergreen Revolution’ — sustainable, ecologically balanced farming — reflected his recognition that technological success had created new vulnerabilities. “He saw soil exhaustion, monocropping, and water stress coming long before they became policy issues,” she says.

Today’s farm distress, from climate volatility to shrinking margins, might have troubled him. “He’d have said our crisis isn’t of technology but of intent,” Jayakumar observes. “He believed in compassion-led science, not profit-led science.”

Also read | Bharat Ratna for MS Swaminathan, PV Narasimha Rao, Charan Singh

That principle guided even his method of dissemination. When he distributed high-yielding seeds in the 1960s, he made sure the poorest farmers received them first. “His model was bottom-up,” she says. “Let the most vulnerable test innovation. If it works for them, it’ll work for everyone.”

The harmony of opposites

Jayakumar’s portrait is ultimately that of a man who reconciled opposites — scientist and humanist, moderniser and mystic. His admiration for Ramana Maharshi wasn’t incidental; it symbolised his belief that inner clarity was as crucial to discovery as external inquiry.

“Silence was his counterpoint to science,” she says. “It helped him see systems — human, ecological, spiritual – as connected.”

For young scientists, she believes, that may be his most durable lesson. “He used to say science without compassion is a waste of everybody’s time,” she recalls. “He meant that curiosity alone doesn’t change the world, but conscience does.”