Vellore Mutiny of 1806: Tamil Nadu’s warriors in India’s fight for freedom that history forgot

The Vellore Mutiny of 1806, sparked by changes in the sepoy dress code and partly aided by Tipu Sultan’s sons, reveals Tamil Nadu’s vital yet often overlooked role in India’s Independence

The Vellore mutiny, or Vellore Revolution, occurred on 10 July 1806, with a large-scale and violent mutiny by Indian sepoys against the East India Company. The revolt lasted one full day, during which mutineers seized the Vellore Fort in northern Tamil Nadu and killed or wounded 200 British troops. The mutiny was subdued by cavalry and artillery from Arcot. Approximately 350 mutineers were killed; with summary executions of about 100 during the suppression of the outbreak, followed by the formal court-martial of smaller numbers.

The flashpoint of the revolt was the resentment towards changes in the sepoy dress code, introduced in November 1805. Hindus were prohibited from wearing religious marks on their foreheads while on duty, and Muslims had to shave their beards and trim their moustaches. To worsen the situation, General Sir John Craddock, Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army, ordered the wearing of a round hat.

The new headdress included a leather cockade and was intended to replace the existing turban. These measures offended the sensibilities of both Hindu and Muslim sepoys, ignoring an earlier warning by a military board that sepoy uniform changes should be “given every consideration which a subject of that delicate and important nature required”.

In May 1806, some sepoys who protested against the new rules were dispatched to Fort Saint George in Chennai. Two of them — a Hindu and a Muslim — were given 90 lashes each and dismissed from the army. Nineteen sepoys were sentenced to 50 lashes each.

Rebellion was partly aided by Tipu Sultan’s sons

The rebellion was also partly aided by the sons of the defeated Tipu Sultan, confined at Vellore since 1799. Tipu’s wives and sons, together with numerous retainers, were pensioners of the East India Company and lived in a palace within the large complex comprising the Vellore Fort. The plotters of the revolt gathered at the fort under the pretext of attending the wedding of Tipu Sultan’s daughter on July 9, 1806. The mutineers had hoped that by seizing and holding the fort, they might have encouraged a general uprising. However, they felt let down when Tipu’s sons were reluctant to take full charge after the mutiny arose.

Two hours after midnight on July 10, the sepoys killed 14 of their own officers and 115 men of the 69th Regiment, most of the latter as they slept in their barracks. Among those killed was Colonel St. John Fancourt, the commander of the fort. By dawn, the mutineers had seized control, and raised the flag of the Mysore Sultanate over the fort. Retainers of Tipu’s second son Fateh Hyder came out from the palace part of the complex and joined with the mutineers.

A British officer, Major Coopes, who was outside the walls of the fort that night, alerted the garrison in Arcot. Nine hours after the outbreak of the mutiny, a relief force comprising the British 19th Light Dragoons, galloper guns, and a squadron of Madras cavalry, rode from Arcot to Vellore, covering 16 miles (26 km) in about two hours. It was led by Sir Robert Rollo Gillespie.

Sir Robert Gillespie quelled the rebellion

Arriving at Vellore, Gillespie found the surviving Europeans, about 60 men of the 69th, commanded by NCOs and two assistant surgeons, still holding part of the ramparts but running short of ammunition. Gillespie climbed the wall with the aid of a rope and a sergeant’s sash which was lowered to him; and, to gain time, led the 69th in a bayonet-charge along the ramparts. When the rest of the 19th arrived, Gillespie had them blow open the gates with their galloper guns, and made a second charge with the 69th to clear a space inside the entrance to permit the cavalry to deploy.

About 100 sepoys who had sought refuge inside the palace were brought out, and by Gillespie’s order, placed against a wall and shot dead. John Blakiston, the engineer who had blown in the gates, recalled: “Even this appalling sight I could look upon, I may almost say, with composure. It was an act of summary justice, and in every respect a most proper one; yet, at this distance of time, I find it a difficult matter to approve the deed, or to account for the feeling under which I then viewed it.”

Gillespie admitted that even a delay of five minutes would have been costly as the mutiny succeeded. In all, nearly 350 of the rebels were killed, and an equal number wounded. Surviving sepoys were later captured by local police to be eventually released or returned to Vellore for court-martial.

After a formal trial, six mutineers were blown away by guns, five shot by firing squad, eight hanged, and five transported. The three Madras battalions involved in the mutiny were all disbanded.

The senior British officers who introduced the new dress code were recalled to England, including the Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army, John Craddock. The orders regarding the ‘new turbans’ (round hats) were also cancelled.

After the incident, the royals imprisoned in Vellore fort were shifted to Kolkata. The Governor of Madras, William Bentinck, too was recalled, the Company’s Court of Directors regretting that “greater care and caution had not been exercised in examining into the real sentiments and dispositions of the sepoys before measures of severity were adopted to enforce the order respecting the use of the new turban.” The controversial interference with the social and religious customs of the sepoys was also removed.

Lady Fancourt's eyewitness account of the Vellore Mutiny

The only surviving eyewitness account of the actual outbreak of the Vellore Mutiny was that of Amelia Farrer (Lady Fancourt, the wife of St. John Fancourt, the commander of the fort). Her manuscript account, written two weeks after the massacre, describes how she and her children survived as her husband perished.

In a personal account, in the Sydney Gazette, on Tuesday, June 14, 1842, was published, “An Account Of the Mutiny at Vellore, by the Lady of Sir John Fancourt, the Commandant, who was killed there July 9th, 1806.”

“Colonel Fancourt and myself retired to rest at 10 o’clock. About the hour of two on Thursday morning, we were both awakened at the same instant, by a loud firing; we got out of bed, and Colonel Fancourt went to the window of his dressing room; he opened it, and called aloud and requested to know the cause of the disturbance; to which he received no reply but a rapid continuance of the firing, by numberless sepoys assembled at the main guard. Colonel Fancourt went down stairs, and in about five minutes after returned to his dressing room, and requested me instantly to bring him a light. I did so, and placed it on the table; he then sat down to write, and I shut the window from which he had spoken to the sepoys, fearing some shot might hit him as he sat, for they were still firing in all directions about the main guard. I looked at the Colonel and saw him as pale as death.

…I enquired (from an officer) what the matter was. He said it was a mutiny, and that every European had already been murdered on guard but himself, and that we should all be murdered. I made no reply but walked away to my room where my babes and female servants were. The officer went out at the opposite door of the hall, where we had spoken together, and never got downstairs alive, being butchered most cruelly in Colonel Fancourt’s dressing room.

... They were at this time firing on the ramparts — and, apparently, in all parts of the fort, though at the main guard, and the barracks, all seemed quiet. They were then employed in ransacking all the houses, intent upon murder and plunder. ...About an hour after, I was told by the surgeon of the 19th that my husband was in danger, but that worse wounds had been cured. They were flesh wounds. Hope still made me think that he would recover. I could not even ask to see him, thinking the sight of me would agitate him too much. Alas! too late I found there was no hope of him from the first, for he breathed his last about four o’clock the same evening. Thank God, he died easily.”

Incidents in Tamil Nadu

There were innumerable incidents during the British Raj in Tamil Nadu wherein freedom fighters carried out physical attacks, or symbolic acts like hoisting of the national flag, music performances of patriotic songs that stirred the masses, and films that had characters hailing the freedom struggle or patriotic songs.

In one such incident, British Collector Ashe was assassinated. A freedom fighter, Vanchinathan of Tamil Nadu, assassinated the then British Collector Ashe at the Maniyachi railway junction, between Tirunelveli and Tuticorin. Robert William d’Escourt Ashe (23 November 1872 – 17 June 1911) was the acting Collector and District magistrate of Tirunelveli district in Madras Presidency during the British Raj.

Ashe had played a significant part in the closure of the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company, started by V.O. Chidambaram Pillai to take on the British India Steam Navigation Company that had for long monopolised trade in the southern part of the Bay of Bengal. He was also responsible for charging V.O.Chidambaram Pillai and a colleague, Subramanya Siva, for which they were convicted.

After the shooting, Vanchinathan ran along the platform and took cover in the latrine. Some time later, he was found dead, having shot himself in the mouth. Vanchi was accompanied by a youth named Sankara Krishna Aiyar who ran away, but was afterwards caught and convicted. The Maniyachi station was later renamed to include the name of Vanchi.

Thookkumedai (Gallows) Rajagopal

Rajagopal and a group of freedom fighters had a clash with guards during which they set a shed on fire. They tried to escape by tying up the guards on duty and snatching their guns and other weapons from them. An English officer named W. Loane Durai began attacking them with the bayonet of his gun. The freedom fighters felled Loane Durai by stabbing and slashing him with their weapons. This incident is mentioned in the Thoothukudi District Gazetteer. The murder trial was completed in February 1943 and the verdict was delivered. Rajagopala Nadar was sentenced to death. It was also announced that the sentence would be carried out on 30 April 1943.

The British government, not wanting Rajaji to come to London to plead the case, advised the Governor General of India to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. Accordingly, on 23 April 1945, the Governor General issued the Commutation of Sentence Order. Two years later, they were all released on the occasion of India’s independence. Rajagopala Nadar was referred to as ‘Thookumedai’ Rajagopal. A memorial pillar was also erected in 1997 at Kulasekarapatnam to commemorate this event.

Tiruppur Kumaran

Kumarasamy Mudaliyar was born in Chennimalai in present-day Erode district of Tamil Nadu. He founded the Desa Bandhu Youth Association and led protests against the British. He died from injuries sustained from a police assault on the banks of Noyyal River in Tiruppur during a protest march against the British government on January 11, 1932. At the time of his death, he held aloft the flag of the Indian Nationalists, which had been banned by the British, giving rise to the epithet Kodi Kaatha Kumaran in Tamil - 'Kumaran who protected the flag'. He died when he was just 28.

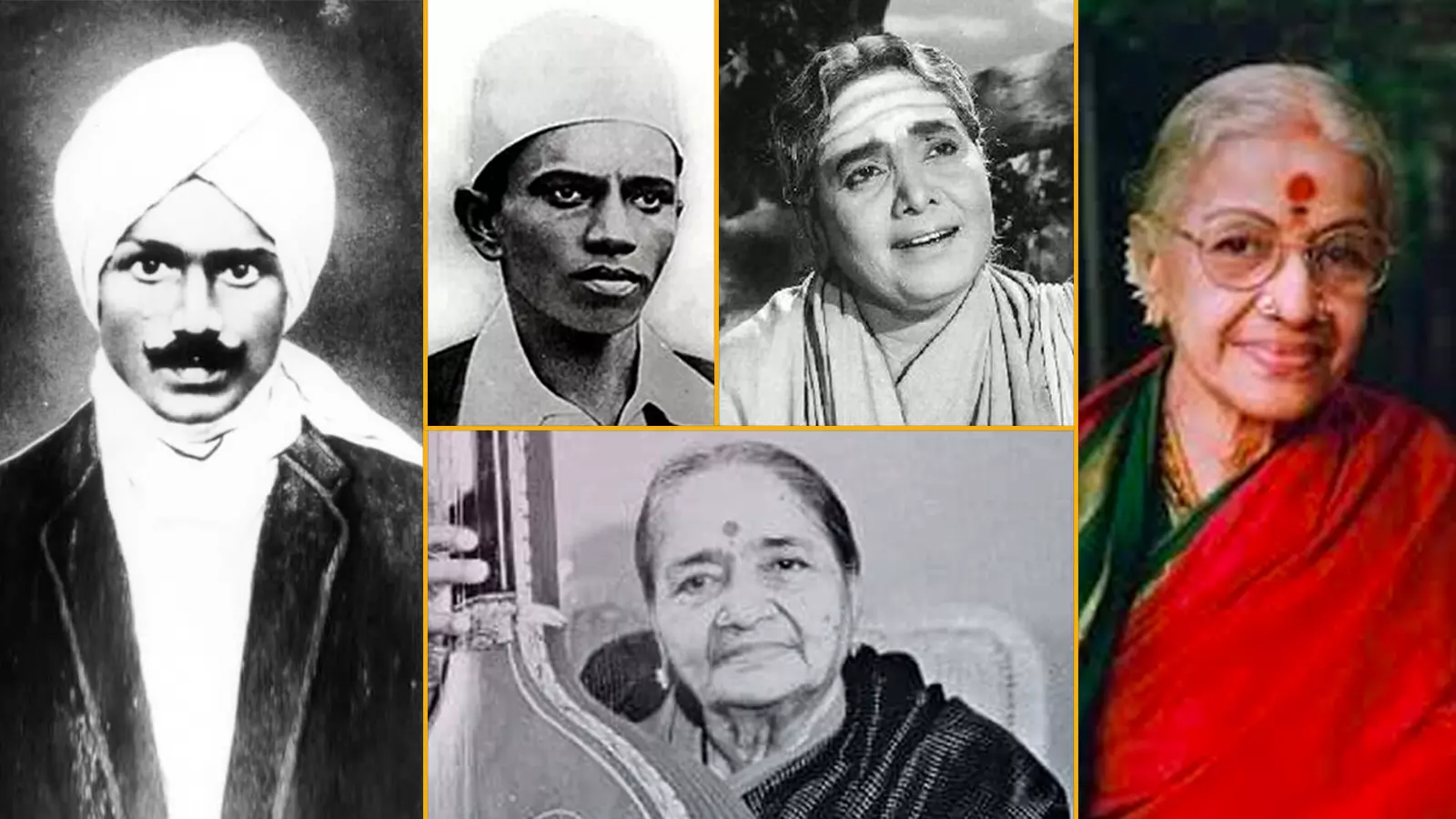

Subramania Bharati

The national poet’s writings and poems stirred the people and inspired them to join the freedom movement. His works were applauded by leaders from all over the country, including Mahatma Gandhi, who hailed him as a treasure during a visit to Chennai. He died young at the age of 38 before India became free.

Musicians MS Subbulakshmi, DK Pattammal, KB Sundarambal

Several musicians, including MS Subbulakshmi, KB Sundarambal, and DK Pattammmal, rendered patriotic songs to arouse the masses, and their music programmes were special events at Congress national sessions, and hailed by Gandhiji, Nehru, and other leaders. Many of these songs were also used in films.

Mainstream newspapers in Tamil Nadu carried the speeches of the Congress leaders and the freedom movement, and helped carry important messages to the masses, including announcements of rallies and agitations which helped people gather at these venues in large numbers. The British Raj tried to clamp down on these newspapers from time to time, but the journalists carried on with their mission. The media in Tamil Nadu inspired presspersons and media owners all over the country through their writings and publications.

Tamil Nadu celebrities from the cultural and literary fields made an immense contribution in motivating the people to plunge themselves in the freedom struggle and helped make it a mass movement through the mass media.

The contribution of Tamil Nadu, why even South India, has not grabbed enough attention in the national media which has also unwittingly given an impression that the freedom movement was largely confined to North and West India.