- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

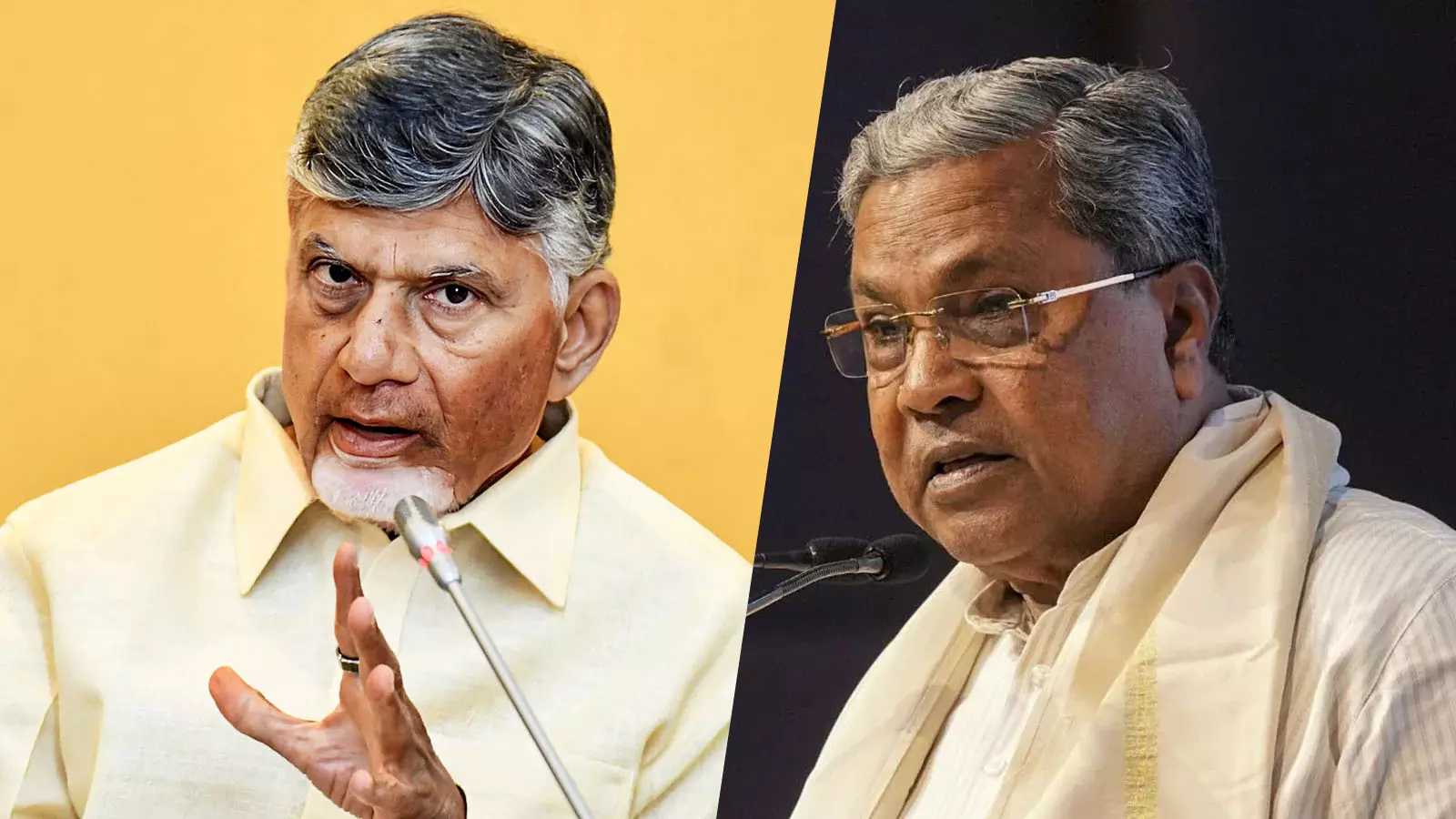

Closure reports by agencies reporting to accused CMs spark debate on conflict of interest and the necessity for neutral probes in political cases

Now, we are no strangers when it comes to politicians according themselves privilege—serving the people by blocking their movement as VVIP convoys move on the road to pitching pro-people schemes as a personal favour to the electorate.

But the biggest privilege they accord to themselves when they come to power is to become judge, jury, and executioner in matters involving their own impropriety—even corruption. India has a history of such chief ministers. And the latest examples come from two South Indian states—Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.

Both CMs, accused of corruption, were tried for it in courts—and upon coming to power, acquitted! Same courts, same police. The only thing that changed—from Opposition to returning to power. Were they victims of political propaganda when in Opposition? Or a beneficiary of the perks of power? Let us look at these cases one by one.

Three cases involving Chandrababu Naidu

The last couple of months have seen three cases involving Andhra CM Chandrababu Naidu being closed. First, the skill development case.

On September 9, 2023, the former Jagan Mohan Reddy government’s CID arrested Naidu in what they called a skill development fraud—which the CID then claimed involved an embezzlement of Rs 371 crore. The CID submitted in court that the former CM Chandrababu Naidu, government officials, Siemens, and DesignTech had inflated project costs and siphoned off money through a conspiracy.

Also Read: Andhra Pradesh: CID registers FIR against TDP chief Naidu in Fibernet scam case

Naidu spent 53 days in jail. He was only granted bail later by the Andhra High Court on health grounds. Naidu returned to power in Andhra in 2024 after decimating Jagan’s party in the polls. Almost 18 months into power, in January 2026, with the state CID reporting to Naidu now, the agency filed a closure report citing lack of evidence. The court accepted it and gave Naidu a clean chit.

Liquor fraud case

Two other cases of self-acquittal related to Naidu surfaced in December 2025. The ACB Court in Vijayawada closed a liquor fraud case filed against him during Jagan’s rule, which alleged irregularities in giving permissions to certain distilleries. The allegation back then was that it caused the exchequer a loss of Rs 1,300 crores.

The liquor case was filed by the Andhra CID in October 2023—just ahead of the 2024 assembly elections. Exactly two years into power, and the same CID under Naidu’s rule filed an NOC declaring him not guilty.

FiberNet case

The third and the last in the case-closing spree also came in December 2025. There again, the Vijayawada ACB court dismissed a FiberNet case against Chandrababu Naidu and acquitted all the accused.

In February 2024, the CID, under Jagan rule, filed a chargesheet in the Vijayawada ACB court, naming Naidu as the main accused. The allegation—a Rs 114-crore scam. The agency alleged that tender processes for AP FiberNet project were manipulated to favour certain specific companies. The same CID then found no strong evidence against their present CM.

Also Read: SC slams ED’s political misuse, junks plea against Siddaramaiah’s wife in MUDA case

While Jagan’s party has been protesting in the state against these self-acquittals, Naidu’s party calls them fake cases, aimed to persecute political opposition just ahead of elections.

Siddaramaiah and MUDA case

The next exercise in self-acquittal comes from Karnataka. In July 2024, sitting CM Siddaramaiah was accused by the opposition BJP of getting Mysuru Urban Development Authority (MUDA) to allot 14 prime sites to the CM’s wife.

Amid the uproar, the CM constituted a judicial commission headed by Justice PN Desai to probe the matter. Later that year, the Lokayukta and the ED (under the central government) began parallel investigations, but the state government pushed for the findings in the judicial panel’s report it had commissioned. The report came out in September 2025.

And guess what, it favoured the CM. Justice Desai’s panel report stated that there was “no illegality” in the site allotment and that lower-level officials had erred in interpreting the rules. The Karnataka Cabinet officially accepted the report, effectively ending the threat to the chief minister at the state level.

Legally, Siddaramaiah had earned a big legal victory for himself when first, the Karnataka High Court quashed the summons issued by ED in this case. And then later, in July 2025, the Supreme Court pulled up ED for “being used to fight political battles”.

Also Read: MUDA case: HC issues notice to CM Siddaramaiah’s wife, her brother

Just last week, a special court for public representatives has reserved its order in the same case on the “closure report” filed by the Karnataka Lokayukta Police. No prizes for guessing—this report, too, cites “lack of evidence”. The judgement is likely to be pronounced on January 22.

The merits of these cases are obviously a subject of detailed legal and political arguments. The point here is simple—when an agency reporting to you clears your name, should it really be considered a clean chit? Or should politicians hand over probes against themselves to independent and neutral agencies and observers to be cleared—both on paper and in the minds of the public?

Yogi Adityanath and vanishing cases

While the two recent examples are from the south, one cannot forget the famous case of Yogi Adityanath. Where, immediately on assuming power, the CM removed prosecution sanction against himself in a 2007 hate speech case. And later that year, Yogi introduced the “Uttar Pradesh Criminal Law Amendment Bill” in the UP Assembly, aimed at withdrawing 20,000 “political” cases. This Act became a law. And within minutes, cases as old as 22 years against him vanished.

‘Washing machine’

And why should we restrict ourselves to just chief ministers? Haven’t we all heard of the “washing machine” arguments in the ED and CBI cases against political leaders as soon as they jump ship from the Opposition to the BJP? From Praful Patel to Himanta Biswa Sarma to Suvendu Adhikari—the list is long.

Also Read: MUDA scam: ED attaches 92 more properties worth Rs 100 crore

As the country has started joking about these cases, the joke is really on us. Do we really know the reality? Or is the nature of political cases cyclical in nature—that will never give any of us a true picture?

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas, or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)