- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

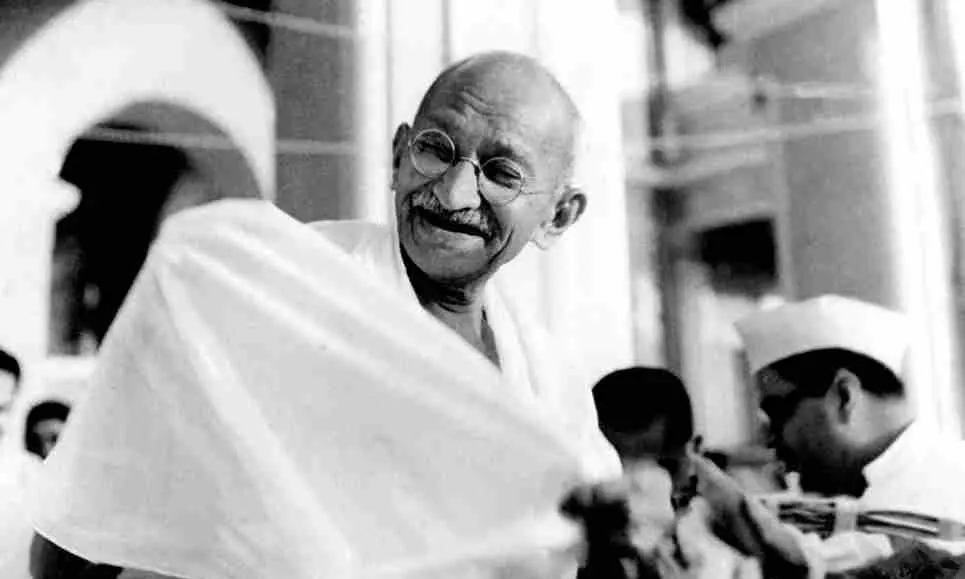

Mahatma Gandhi was unique in India’s Independence struggle because he was not just a politician or strategist, nor just a saintly figure. His mode of politics could be intelligible and compelling to both elites and common people, albeit in very different ways. Image: Wikimedia Commons

He was a shrewd strategist for modern intelligentsia and a saintly figure, who fasted, prayed, and led a simple life, for the illiterate masses

Mahatma Gandhi’s political role in India’s Independence struggle was unique because he succeeded in uniting two otherwise disconnected worlds of political reasoning: the modernist discourse of elites and the traditional symbolic universe of the masses.

Before Gandhi, India’s resistance to colonial rule was divided and fragmented. Elite dissatisfaction was articulate but lacked popular backing, while peasant uprisings were intense but geographically restricted. The colonial state could easily suppress one and ignore the other.

Semiotic dualism

Gandhi’s originality lay in bridging these divides through what scholars call a semiotic dualism: a mode of politics that could be intelligible and compelling to both elites and common people, albeit in very different ways.

Gandhi’s first experiment in India, the Champaran Satyagraha of 1917, exemplifies this synthesis. For peasants, his defiance of the magistrate’s order to leave Champaran made him a moral redeemer who stood against oppressive indigo planters. For elites, Gandhi’s reliance on legal procedure, documentation, and negotiation marked him as a strategist who avoided anarchic rebellion.

This ability to translate peasant suffering into constitutional protest enabled nationalism to speak in two registers at once.

Also read: How Gandhi used the 4 modes of abhinaya to manage the freedom struggle

At one level, Gandhi appeared to the modern intelligentsia as a shrewd strategist. His trial in 1922 is a classic example: he pleaded guilty to charges of sedition but framed his guilt in ways that challenged the moral legitimacy of colonial law itself.

Shrewd strategist, saintly figure

To educated Indians, he was a lawyer who understood the colonial system inside out and turned its legal logic against itself, forcing judges into dilemmas between punishment and restraint. His actions could thus be read in terms of rational calculation, tactics, and political manoeuvre, the familiar register of modern political reason.

At another level, Gandhi appeared to the ordinary peasants and illiterate masses as a saintly figure, almost miraculous in his defiance.

In rural imagination, the state was a distant, oppressive force that was rarely challenged by ordinary men and women. For peasants, Gandhi became the Mahatma, the great soul, who took upon himself the suffering of the weak; who fasted, prayed, wore simple homespun clothes, and embodied an older cultural vocabulary of sacrifice and redemption. His politics thus resonated with traditions of cyclical time and miraculous deliverance: events that seemed at once ancient and new, familiar yet extraordinary.

This dual intelligibility was Gandhi’s greatest achievement. Gandhi’s uniqueness was not simply in preaching nonviolence but in constructing a politics that was legible to two very different audiences.

Fasting appeared to educated Indians as political pressure, but to ordinary Hindus and Jains it resonated with long traditions of penance and purification

To British officials, he was a shrewd strategist who staged agitation within the limits of legality; to peasants, he was the Mahatma who embodied sacrifice and redemption.

Dual register

The very same act could thus generate divergent meanings: the breaking of the Salt Law in 1930 was condemned by The Times in London as seditious, yet celebrated in Bhojpuri folk songs as a sacred miracle.

The Salt March itself exemplified this dual register. It functioned as a political strike against the colonial monopoly for elites, but for villagers, it was a sacred act that transformed a humble substance into a symbol of freedom.

Also read: Can Gandhi’s legacy save India today? A historian’s deep insights

Similarly, fasting appeared to educated Indians as political pressure, but to ordinary Hindus and Jains, it resonated with long traditions of penance and purification.

Unlike other nationalist leaders, who spoke mainly in the language of law, reform, or economic progress, Gandhi consciously deployed a broader semiotic register, silence, fasting, spinning, prayer, and simplicity. These were not empty rituals but political symbols that communicated across linguistic and cultural divides. He bypassed the suspicion peasants held toward the written word and connected instead through embodied practices that carried moral weight in Indian culture.

Diglossia nationalism

In addition, Gandhi cultivated what might be described as a diglossia nationalism.

The nationalist movement acquired the capacity to operate in two distinct registers: English, the language of the colonial state and the educated elite, and the regional vernaculars, which carried the resonances of everyday life for the masses. This bilingualism enabled elites from different provinces to forge coalitions across India, while allowing fragments of nationalist discourse to circulate among ordinary people with minimal translation.

Yet, for the vast numbers who were illiterate or who regarded the written word as the preserve of elites, Gandhi turned to the power of symbolism to bridge these linguistic worlds. The spinning wheel, the goat, or the handful of salt were never abstract slogans; they were material and familiar objects, saturated with cultural meaning.

The spinning wheel, the goat, or the handful of salt were never abstract slogans; they were material and familiar objects, saturated with cultural meaning

To elites, such objects distilled complex political critique into simple, repeatable emblems of resistance. To villagers, they sacralised the ordinary, transforming everyday life into a site of nationalist struggle. Through this symbolic condensation, Gandhi ensured that a movement articulated in two languages nonetheless resonated as a single moral and political project.

Also read: CWC meeting | Congress: Will rededicate to protect Mahatma Gandhi's legacy

A medium who joined two worlds

In short, Gandhi was unique in India’s independence struggle because he was not just a politician or strategist, nor only a saintly figure.

He was both a modern tactician and a traditional redeemer, capable of uniting elites and masses within one broad nationalist movement. By mastering two registers of political communication, he transformed Indian nationalism from a fractured and limited resistance into a movement with unprecedented social depth and spatial reach.

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)