- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

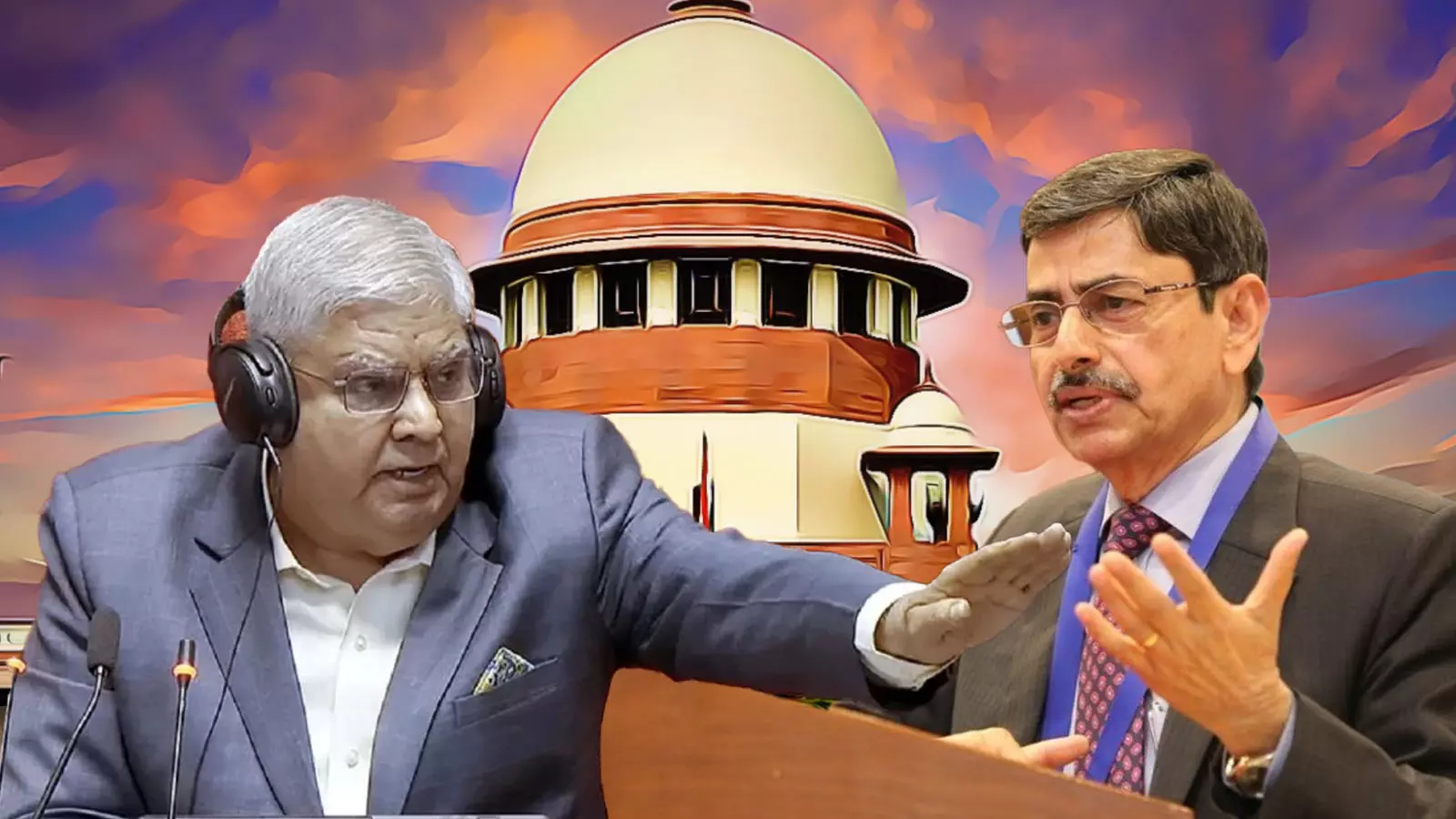

In RN Ravi case, it wasn’t judicial overreach — it was judicial closure aimed to trim further delay in implementing laws passed by a democratically elected govt

The recent standoff between the Tamil Nadu government and Governor RN Ravi's delayed assent to bills passed by the state Assembly has reignited public debate around the limits of gubernatorial discretion and the judiciary’s role in upholding the constitutional order.

Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s criticism of the Supreme Court as a “super parliament” has only added to the noise.

The Constitution places clear limits on the governor’s powers. When it comes to bills passed by a state legislature, the governor is expected to act on the advice of the elected Council of Ministers. The Tamil Nadu case, where several bills were kept pending for months without explanation, challenged this basic principle.

The ruling was less a judicial innovation than a necessary clarification of the Constitution’s intent. Discretion, as outlined in the constitutional scheme, was never meant to be a veto.

The Supreme Court’s intervention was direct: the governor cannot keep bills in limbo indefinitely, and a timeline — three months — was prescribed to make a decision. The ruling was less a judicial innovation than a necessary clarification of the Constitution’s intent. Discretion, as outlined in the constitutional scheme, was never meant to be a veto.

Why Article 142

Critics often point to Article 142, which allows the Supreme Court to issue any order necessary to do “complete justice”, as an unchecked tool of judicial activism. Dhankhar likened it to a “nuclear missile” deployed against the democratic process. Such metaphors miss the point.

Article 142 is rarely invoked, and only when institutional processes break down. In the Tamil Nadu case, it ensured that the court’s ruling would have immediate effect rather than forcing the state to restart a legislative cycle already completed.

Watch | Decoding Dhankhar: The role of Judiciary in Democracy | Article 142

This wasn’t judicial overreach — it was judicial closure, aimed at avoiding further delay in implementing laws passed by a democratically elected Assembly.

Democracy isn’t just about counting votes; it’s about respecting institutional roles and processes. Recent instances from the Waqf Amendment Act to the now-repealed farm laws highlight how parliamentary majorities have been used to push through legislation without meaningful consultation or debate.

Such practices blur the line between democratic mandate and procedural manipulation. When state institutions, including governors, become extensions of political will rather than constitutional guardians, the judiciary’s role in maintaining institutional balance becomes not optional, but essential.

Myth of judicial arrogance

The 2015 decision to strike down the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act has been repeatedly cited as evidence of judicial resistance to reform. But the ruling was rooted in protecting the independence of the judiciary, a feature the Supreme Court has long held as part of the Constitution’s basic structure.

There was no defiance of Parliament’s will in this case, only a refusal to dilute judicial independence through mechanisms that gave the executive outsized influence in appointments. The Constitution allows Parliament wide latitude to legislate, but not at the cost of eroding institutional autonomy.

Also read | Why judiciary must recognise the right to refusal in sexual offences

Another criticism often levelled against the judiciary is its supposed lack of transparency. Judges aren’t elected, and they don’t face direct public accountability. But unlike the executive, the judiciary operates in open court. Judgments are reasoned, written and subject to appeal. Proceedings are public. Orders are recorded.

While concerns around judicial conduct and accountability are valid and judicial reforms are due, it’s incorrect to equate electoral visibility with institutional integrity. Accountability takes different forms in different branches. Transparency in the judiciary flows through process, record and reason.

Shrinking role of states

Recent years have seen a steady erosion of the constitutional balance between the Union and the states. The Tamil Nadu Governor deadlock is one example.

So is the increasing frequency with which centrally-aligned governors withhold or delay assent to state legislation. These are not administrative quirks but coordinated strategies that challenge the federal character of the Indian Republic.

The Constitution does not envisage governors as political counterweights to elected state governments. They are facilitators of the legislative process, not gatekeepers of partisan interest. Where this understanding breaks down, judicial intervention becomes a constitutional correction, not an institutional encroachment.

Planning beyond courtroom

Judicial clarity, however, is only part of the solution. If constitutional balance is to be restored, the conversation must also extend to governance, education and social development.

Skill-building, economic development, public investment and access to opportunity are critical areas where India continues to lag. The overemphasis on elite professions doctors, lawyers, engineers has left out large swathes of the population who could thrive with the right training and infrastructure.

Also read | Governor as catalyst, not inhibitor: When SC showed Raj Bhavan its place

Countries like China and Japan have surged ahead by investing in vocational skills, industrial productivity and early education — not just legal compliance.

States like Gujarat have reported alarmingly high failure rates in school-level exams, pointing to deeper governance deficits. The mismatch between policy priorities and population needs is growing, and political attention remains fixated on symbolic narratives over structural investment.

Restoring constitutional normalcy

The judiciary’s role in these debates has become more visible because other institutions have stepped back or fallen silent. It is not that courts are encroaching on legislative territory, but that they are often the last functioning recourse for constitutional redress.

A functioning democracy cannot treat its Constitution as optional. Nor can it rely on court orders to resolve every governance dispute.(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the article are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)