- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

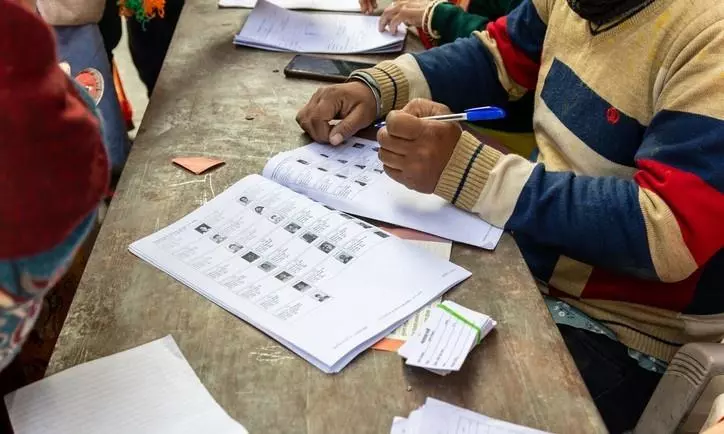

When concerns of manipulations emerge, parties are reacting rhetorically, alleging 'vote chori', rather than proactively preventing exclusions at the booth level

Bihar’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls has triggered one of the sharpest political confrontations in recent years.

Opposition leaders, most prominently Rahul Gandhi, have branded the exercise as a bid at “vote chori” (vote theft), an orchestrated disenfranchisement of vulnerable communities.

Also read | Bihar SIR: SC says confusion 'largely trust issue'; extends claims window beyond Sept 1

The Election Commission (EC) has defended the revision as both lawful and “voter-friendly” while the Supreme Court, though refusing to halt the process, has expressed surprise at the inaction of political parties during the draft-roll stage.

That comment cuts to the heart of the crisis. It is not an isolated bureaucratic episode but a symptom of structural transformations in Indian politics.

Fading party allegiance

Declining party loyalties, shifting modes of politicisation, and the changing nature of clientelism have hollowed out the very networks that earlier safeguarded electoral rolls. In their place, parties increasingly lean on professional consultants and digital strategies, which excel at shaping narratives but are poorly equipped for granular voter list vigilance.

Crux of the issue: Booth-level vigilance vs digital politics

♦ Party loyalties and cadre networks are rapidly weakening

♦ Local activists once ensured accurate and inclusive voter rolls

♦ Parties now rely on consultants and digital strategies instead

♦ These new tools lack capacity for voter list verification

♦ Shift fuels voter roll errors and distrust in the system

The result is a democracy where accusations of manipulation grow louder even as the institutional capacity to detect and correct errors at the entry stage has weakened.

For much of post-Independence India, parties maintained dense networks of local activists whose loyalty to the organisation was reinforced by neighbourhood ties, patronage exchanges, and everyday forms of mobilisation. These cadres were not only campaigners but also informal auditors of voter lists, knowing each household, detecting duplications, and shepherding supporters through bureaucratic processes.

Thinning infrastructure

Today, that infrastructure is visibly thinned. Declining party loyalties among voters, combined with rising political mobility, have eroded incentives for sustaining long-term cadre networks.

Instead, parties increasingly outsource electoral management to consultants whose comparative advantage lies in macro-level messaging, digital targeting, and perception building rather than granular voter-list verification.

The consequences extend beyond roll errors. Changing modes of politicisation from ideological identification to issue-based mobilisations and leader-centric appeals reduce the salience of party identity as a durable anchor.

Also read | Bihar SIR: Is EC using ‘citizenship doubts’ to disenfranchise 3 lakh voters? | Capital Beat

State-mediated patronage

Voters shift preferences across elections. Local activists themselves are less embedded in singular party structures. And clientelism, once tied to continuous servicing of households and neighbourhoods, has morphed into event-based transfers such as welfare schemes, cash incentives, or last-minute mobilisations.

This new model privileges state-mediated patronage and consultant-mediated campaigns over the painstaking, continuous engagement that earlier clientelistic machines sustained.

The fallout is visible in Bihar. When allegations of wrongful deletions and manipulations emerge, parties find themselves reacting rhetorically, organising protests, invoking “vote chori” charges rather than proactively preventing exclusions at the booth level.

Eroding electoral groundwork

The traditional muscle of cadre-based verification, which once helped anchor public trust in electoral lists, no longer operates with the same density. Instead of volunteers scrutinising draft rolls in each mohalla, parties now rely on centralised data dashboards and war rooms, which struggle to register the nuances of misspelled names, migrant households, or overlapping addresses.

This is not merely a technical shortcoming but a structural shift in how Indian democracy functions. As clientelism changes character from personalised favour exchanges to programmatic or consultant-driven forms, its side effect is the weakening of reciprocal obligations between voter and party worker.

Political parties, untethered from their earlier neighbourhood networks, are left exposed when systemic exercises like the SIR test the robustness of ground-level vigilance. Electoral authorities may insist that the process is “voter-friendly” and correctable, but correction is only as effective as the societal intermediaries who mobilise citizens to file objections, attend hearings, and ensure restoration.

Grassroots accountability

Thus, the debates around Bihar’s voter roll revisions reveal not only the fragility of electoral administration but also the changing sociology of Indian politics. What appears as a technical dispute over deletions in fact signals a shift in how parties interact with citizens: from sustained, relational networks to episodic, consultant-managed mobilisations.

Also read | EC trying to disenfranchise those unlikely to vote for BJP in Bihar: Parakala Prabhakar

The diminishing role of local intermediaries has left electoral processes vulnerable to both bureaucratic error and political mistrust, while the rhetoric of “vote theft” substitutes for the slow work of institutional vigilance. Seen in this light, the SIR controversy is less about partisan manipulation than about the hollowing of the infrastructures that once anchored democratic credibility.

Rebuilding that credibility requires parties to imagine new forms of embedded presence, not a return to older patron-client ties, but innovative modes of grassroots accountability that can coexist with digital campaigning and centralised welfare politics.

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)