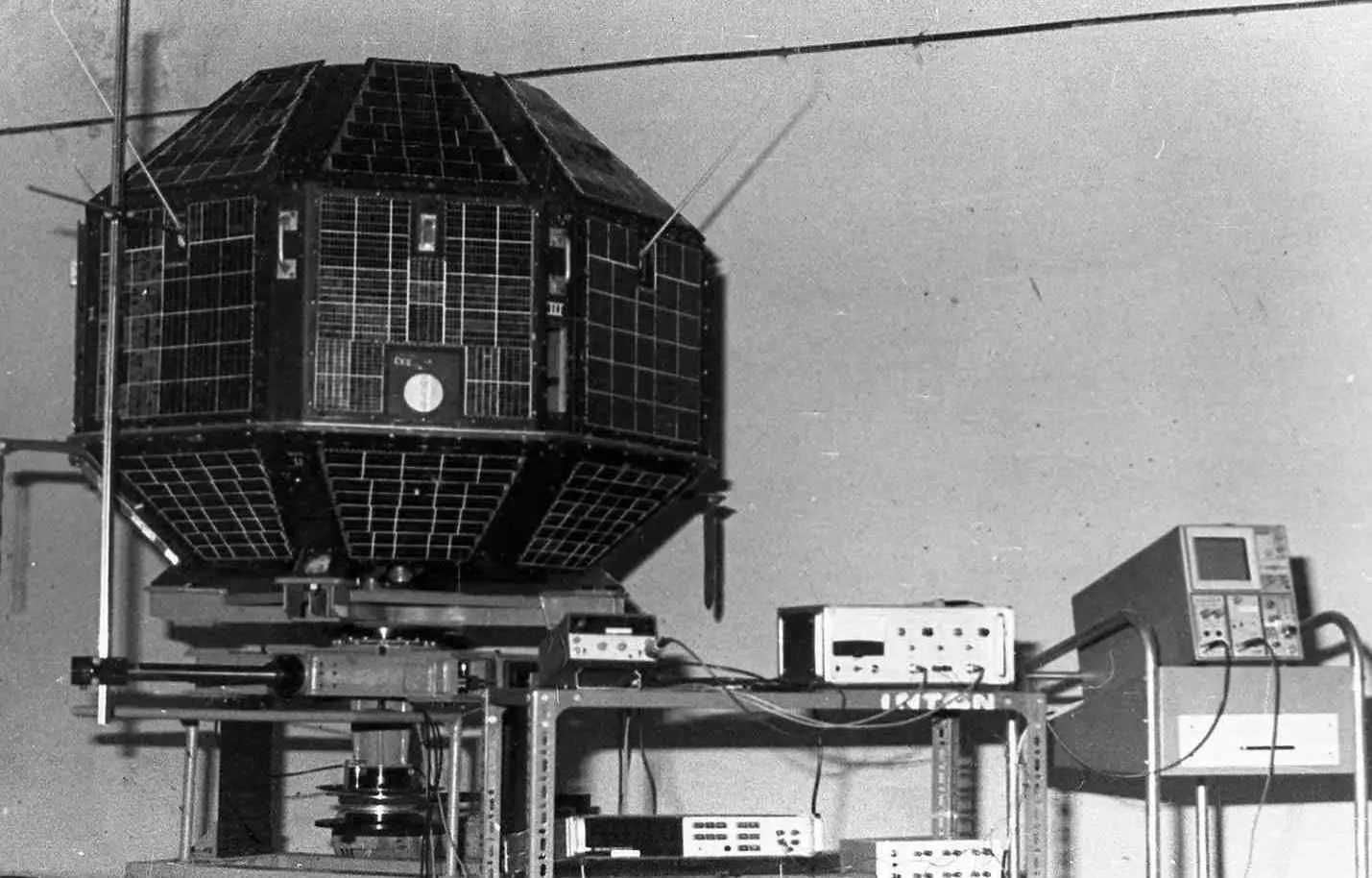

Aryabhata satellite. File photo: ISRO

50 years of Aryabhata satellite: When India imagined, and pulled off the impossible

Named after the fifth-century Indian mathematician, the satellite was built from scratch by a small team of engineers with little or no experience

On April 19, 1975, India did something quietly spectacular. From a Soviet launch site at Kapustin Yar, a 360-kg Indian satellite named Aryabhata — after the fifth-century Indian mathematician and astronomer — was sent into orbit aboard a Kosmos-3M rocket. For a country still only a few decades into Independence, the moment felt improbable. Yet there it was: India, in space.

Also read: ISRO achieves de-docking of SpaDeX satellites at first attempt

The journey to that moment had begun over a decade earlier, largely shaped by Dr. Vikram Sarabhai, the physicist who saw space not as a vanity project but as a tool for development in a fledgling independent nation — broadcasting lessons to rural classrooms, mapping weather, enabling communication. In 1968, Sarabhai, then Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission and Director of the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad, asked Professor UR Rao, then an associate professor at PRL, to come up with a plan to develop an experimental satellite. Though Sarabhai asked Rao to head the project in response to the latter’s impressive plan, he initially expressed hesitation — but almost a year later, Rao agreed to lead the effort.

Rao recruited engineers from the Space Science and Technology Centre (SSTC) in Trivandrum (which later became the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre), forming the newly established Satellite Systems Division (SSD). Three joined from the Structures Group and 25 from PRL. Rao and his team set out on an ambitious mission to build India’s first satellite. The American Scout rocket was chosen as the launch vehicle for its comparatively low cost. The decision was to make a 100 kg satellite, aligned with the Scout rocket’s payload capability.

Twists and turns

In April 1971, the Soviets made an offer to Indira Gandhi — relayed via DP Dhar, India’s ambassador in Moscow — that changed everything. She handed over the letter to Sarabhai, who brought Prof Rao into the loop. The Soviet Academy of Sciences had expressed interest in space cooperation, and Rao was asked to meet the Russian ambassador in New Delhi. The USSR was clearly uneasy about India edging too close to the United States.

Also read: Space involves more than excitement; it's time-intensive science: ISRO chief

Where were we in the story? A group of engineers under Prof. Rao was building a small satellite, working with various institutions to develop payloads — and the Soviets were about to make an offer the Indian team wouldn’t be able to refuse.

Signing the Aryabhata agreement are BN Petrov (seated left) and Satish Dhawan (right). Standing from right are Prof. UR Rao, MA Vellodi, PD Bhavsar, A Bogomolov, B Novikov, V Kovtunenko, and another official. File photo: ISRO

One moment captures the geopolitical tension neatly. The Soviet ambassador to India, Nikolay Pegov, casually asked Rao: “How much did China’s first satellite weigh?” At the time, India’s satellite was designed to weigh 100 kg. China’s, launched on April 24, 1970 — Dong Fang Hong 1 — weighed approximately 173 kg. The message was clear. Soon after, the Indian team reworked its plans to meet the implied challenge.

Also read: India is amazing from space, highlighted by Himalayas: Sunita Williams

India’s upcoming satellite would now weigh 358 kg. By their August 1971 meeting with the Russians, Rao and team were ready with the conceptual design for a 360-kg satellite, with three scientific payloads selected by an expert committee.

Building satellite at Peenya sheds

The Soviets, eager to upstage China, agreed to launch it. The Kremlin’s proposal came through formal channels, but its motivations were unmistakably geopolitical. The counteroffer: a free launch.

The unexpected passing of Sarabhai in December 1971, fortunately, did not leave a leadership vacuum. Prof. Satish Dhawan was soon to step in, but he had to be at Caltech (California Institute of Technology) for an assignment for about a year. Under Prof. MGK Menon’s interim chairmanship, the Indo-USSR deal was sealed; he also played a key role in securing Rs 3 crore in government funding for the project from the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

The late Prof. Rao, who later headed ISRO, recounted in an interview how things began to align. Indira Gandhi cleared the project budget. The historic agreement for the launch of India’s first satellite from a Soviet vehicle was signed on May 10, 1972, between M Keldysh, President of the USSR Academy of Sciences, and Prof. MGK Menon. Rao was named Project Director on the Indian side; Dr. VM Kovtunenko held the same role for the Soviets. Prof. Satish Dhawan — who would soon head the Indian space programme — returned from sabbatical and stepped into Sarabhai’s shoes.

Photograph taken moments before the first signal was received from Aryabhata at Bear Lake. File photo: ISRO

Rao secured four asbestos-roofed sheds in Bangalore’s Peenya Industrial Area after persuading Karnataka’s Industries Secretary, Satish Chandra. The Peenya facility — formally inaugurated in September 1972 and now called the Indo-Soviet Satellite Project (ISSP; later renamed the Indian Scientific Satellite Project) — expanded to include two more sheds and a total staff count of 150, including technicians and auxiliary staff.

And that’s where the satellite took shape — built from scratch by a small team of engineers with almost no experience in building satellites. Rao even procured some components for the satellite on a loan-and-replacement basis from, behold… NASA, through his contacts. An Indian satellite. A Soviet rocket. And some of the components sourced from the Soviet Union’s Cold War rival.

How Aryabhata name was chosen

Rao and his team had to design and build everything: power systems, telemetry, attitude control, thermal regulation. In early 1975, Rao and others recommended three names for the satellite to Indira Gandhi: Aryabhata, Jawahar, and Maitri (to acknowledge Indo-Soviet friendship). She chose the first.

The launch went well, placing Aryabhata into an orbit with an apogee of 620 km, a perigee of 562 km, and an inclination of 50.7 degrees. About 90 minutes after launch, ground stations at Bears Lake, SHAR, and Bangalore received strong telemetry signals from the satellite — that’s the rocket scientist’s equivalent of a WhatsApp double tick.

The Indian and Soviet teams’ excitement was sky-high. Except for three scientific instruments that had to be shut down due to an onboard power failure, regular operations continued for the satellite’s designed operating life of six years.

Industrial sheds in Peenya, Bangalore, where Aryabhata was designed and developed under the guidance of Prof. UR Rao. File photo: ISRO

The mission was declared a success. More importantly, it made a statement. India wasn’t just joining the space club — it was building its own satellites, and soon, its own launch vehicles. Aryabhata wasn’t just a satellite. It was proof that a nation could imagine the impossible — and then go on to design, fabricate, test, and build a functioning satellite with sound on-board systems, piece by piece, in a cluster of sheds.

Fifty years on, the legacy created by Aryabhata — and by India’s satellite and rocket pioneers — lives on in every successful launch, every new satellite. Each time an ISRO rocket lifts off, there’s a little bit of Peenya in the flame trail.