Bihar SIR: EC defends voter deletions amid SC scrutiny; what next?

People need to know: What documents are required? What if they’ve lived elsewhere temporarily? What if their only ID is Aadhaar or a ration card?

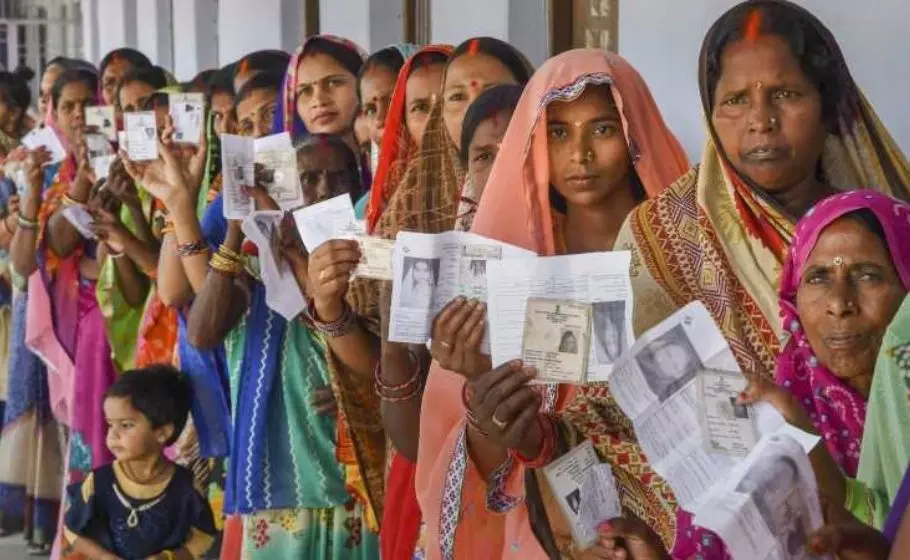

As the Supreme Court examines the Election Commission’s handling of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar, the EC’s affidavit has sparked concerns. By rejecting Aadhaar, ration cards, and even voter ID cards as valid proof of citizenship for electoral rolls, the EC may be paving the way for mass voter disenfranchisement. Senior journalist Puneet Nicholas Yadav explains the implications, legal grey zones, and what to watch out for ahead of the next hearing.

How do you interpret the Election Commission’s clarification that Aadhaar, ration card, and voter ID mismatches are not being used to delete names from electoral rolls?

This affidavit is cleverly drafted, but perhaps too clever by half. The Supreme Court had earlier directed the EC to consider Aadhaar, voter ID, and ration cards as valid proofs of identity. Though the court didn’t make this mandatory in its written order, it had orally observed that the EC could explain its rejection if needed. The EC used that as cover to simply say, “we considered and rejected.”

The EC's reasons for rejecting these documents are deeply problematic. First, it claims Aadhaar isn’t proof of citizenship, only of identity. Legally, that’s correct—but Aadhaar has been made mandatory by the same government for everything from passports to driving licenses. The Representation of the People Act was amended to include Aadhaar. Now rejecting it makes no sense, especially since Aadhaar is the only document many people possess.

Second, the EC says the voter ID itself is suspect—because the SIR is meant to reassess all voters, the fact that someone holds a voter ID doesn’t validate their eligibility. That’s absurd. If the EC questions its own previous processes for issuing EPICs, it is essentially casting doubt on the entire electoral system.

Also read: EPIC, Aadhaar, ration card not valid for Bihar voter roll revision: EC to SC

And third, it dismisses ration cards by calling them “bogus.” But the same government has boasted about distributing free rations to 80 crore people during the pandemic—using ration cards. Is the EC now saying that this distribution was a scam? That those 80 crore people don’t exist? This raises serious questions about governance, not just electoral policy.

The EC says disenrollment under SIR does not mean termination of citizenship. How significant is that clarification, politically and legally?

Legally, the EC is right—it cannot terminate anyone’s citizenship. But politically and practically, that distinction collapses.

If the EC says someone isn’t a citizen and therefore removes them from the rolls, it’s effectively saying they don’t legally belong here. That list can then be passed to the Ministry of Home Affairs, which can initiate action—putting people in detention centres, beginning deportation processes, etc.

And who are these people? Mostly the poor, the marginalised, and minorities—especially in Bihar’s Kosi-Seemanchal region. These are the citizens least capable of fighting the system. So, while the EC walks away after conducting elections, lakhs of people could face legal and existential crises.

Also read: Bihar electoral roll anomalies: 11,000 voters ‘not traceable’? | Interview

Does the EC’s affidavit adequately address fears of mass disenfranchisement in Bihar, especially among marginalised groups?

Not at all. In fact, the data provided by the EC raises more questions than answers.

Out of 7.9 crore voters, the EC says it has already deleted 52 lakh names. That’s nearly 7 per cent—and the process is ongoing. Of those, 18 lakh are supposedly deceased. But the last Lok Sabha election was only a few months ago. Were these people alive and voting then? Or did they all die in just six months? That would mean 900 people dying per day in Bihar—which is absurd and alarming.

Another 26 lakh were removed because they "moved out of Bihar". But many Indians remain registered in their native towns while living elsewhere. The EC had earlier proposed systems to help migrants vote remotely—now it’s punishing them for being away.

Seven lakh names were deleted for being registered in multiple locations. But even if we accept that, it doesn’t explain the EC’s refusal to accept widely held documents like Aadhaar or ration cards.

The numbers themselves reveal how flawed and inconsistent this process is.

What are the possible next steps in the Supreme Court hearings?

The process now moves to the petitioners. They will file a rejoinder to the EC’s 88-page affidavit, contesting the rejection of Aadhaar, EPIC, and ration cards.

During the July 28 hearing, the Court will assess both the EC’s defence and the petitioners’ reply. It could accept the EC’s position, accept parts of it, or reject it entirely.

There’s also a strong possibility that the petitioners will ask the court to stay or even scrap the entire SIR process in Bihar. So the hearing is critical—not just for Bihar, but for other states too. Because the EC wants to roll out this model elsewhere.

Also read: EC's SIR in Bihar a precursor to One Nation, One Election? Talking Sense With Srini

As this process continues, what should voters and watchdog groups be vigilant about—especially with five states heading into elections next year?

Everything hinges on the Supreme Court’s ruling on July 28. We all—voters, journalists, civil society—need clarity on what happens next.

The EC wants to implement SIR across India. If this Bihar model is accepted, other states could see similar disenfranchisement.

People need to know: What documents are required? What if they’ve lived elsewhere temporarily? What if their only ID is Aadhaar or a ration card?

Until these questions are answered with clarity and fairness, trust in the electoral process—and faith in democracy itself—will remain under threat.

(The content above has been generated using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.)