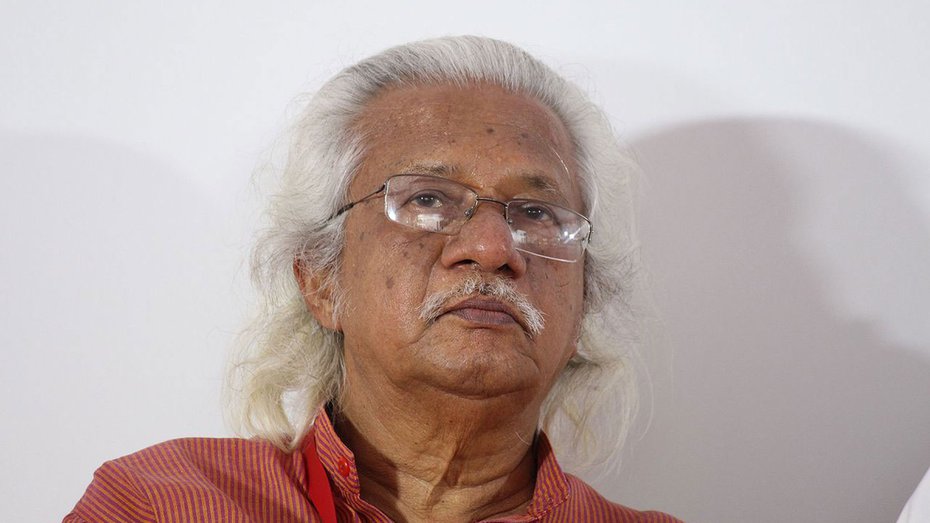

Malayalam cinema: Why Adoor's criticism of Kerala's film funding model falls flat

Critics say the legendary director himself benefited extensively from public film funding throughout his career, both from the Kerala government and NFDC

Legendary filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan's caustic comments at the concluding ceremony of the Film Policy Conclave in Thiruvananthapuram, has stirred up a hornet's nest in Kerala's film and cultural circles.

Speaking on stage at the conclave, legendary filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan had questioned the state government’s initiative to fund films by women and SC/ST directors, suggesting that most lacked adequate training. In what many perceived as a dismissive tone, he cautioned against what he termed as representation-based funding, arguing that allocating ₹1.5 crore to such filmmakers without proper training could compromise artistic merit.

Within hours, the backlash began. Critics pointed out that Adoor himself had benefited extensively from public film funding throughout his career, both from the Kerala government and the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC).

For many, his comments struck a nerve, not because who said them, but because they appeared to overlook the fact that public money was finally reaching people it rarely had before.

KSFDC-funded films

Over the last two years, the Kerala State Film Development Corporation, under a special initiative, has funded eight films directed by women and SC/ST filmmakers.

Six of these have already been released. Though, they may be considered ‘modest’ films in box-office terms, they represent a significant shift in Indian cinema. Consider the details. Three of the films were directed by women—Divorce, B 32 Muthal 44 Vare, and Nila.

Each was allocated a budget between ₹1.46 and ₹1.50 crore, a rare scale of support for debutant women filmmakers. The themes they explored were equally bold, showcased bodily autonomy, loneliness, friendship, the fluidity of gender and age.

Low revenues

Yet, even the most commercially successful of the three films, earned just under ₹7 lakh.

Also read: Kerala Film Conclave ends in uproar over Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s funding remarks

The other three films helmed by directors from SC/ST backgrounds too received state backing of over ₹1.4 crore each. The total revenue from these three films, as per provisional data, remains under ₹6.2 lakh.

Critics have pounced on these figures, pointing to them as proof that the scheme is economically unviable. But to judge these films by box-office returns alone is to miss the broader point. These films were never designed as commercial ventures.

They were public investments in storytelling or tools to widen the frame of who gets to speak, and whose stories are heard.

Boon for marginalized voices

Sruthi Sharanyam, the director of Malayalam drama, B 32 Muthal 44 Vare, told The Federal, “It’s been two years since my debut film released under the government scheme, and despite some attention, no producer has approached me since. I’ve knocked on many doors, sent messages, but I received no replies. Without financial backing, self-producing is impossible.”

Further, she pointed out, “Those with privilege can’t grasp how hard it is for women and marginalized voices to break in. This scheme gave me my first chance, though it also came with personal, financial, and emotional costs. I’ve faced insults and lost friendships, but I’ve never spoken against the project, because without it, I wouldn't have had the opportunity to make my first film.”

Indeed, few debutant women or Dalit filmmakers get to work with over a crore in funding and guaranteed distribution. The scheme offers not just money, but mentorship, infrastructure, and screening support, allowing the directors to focus on craft rather than survival.

For many of them, it’s a first chance at making cinema on their own terms. Everyone knows the scheme isn’t above criticism or perfect in execution. Even the directors themselves have raised concerns but all of them recognise its significance.

Also read: Gender and labour rights dominate Day 1 of Kerala Film Policy Conclave

“Those who genuinely believe in equality don’t oppose reservation. The real issue isn’t the process—Adoor knows well that only one or two films are selected from hundreds of scripts after rigorous scrutiny. What’s troubling is the attitude behind the question itself,” said V S Sanoij, director of the critically acclaimed Ariku, a film that explored the complexities of caste and was made under the government-backed scheme.

Cultural justice is crucial

To understand why this matters, one only has to look at the broader national picture. Institutions like NFDC and Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT) have supported independent and documentary cinema for decades, but they remain limited to the general category, often serving the upper caste and class.

However, PSBT typically funds non-fiction films with modest grants under ₹15 lakh. NFDC’s fiction film scheme, while valuable, has long been criticised for favouring established names and lacking transparency.

Kerala’s initiative, in contrast, is unapologetically political. It sets aside funds specifically for those historically excluded from the industry. It centres on first-time directors and it’s backed by a state that has declared cultural justice a public responsibility.

Saji Cherian, minister for cultural affairs, had explained the purpose of this initiative. “For nearly a century since the first Malayalam film was made, filmmakers from SC/ST communities were denied space in the mainstream. And even today, how many women have had the opportunity to direct films in Malayalam cinema?”

“This is one of the most progressive projects our government has undertaken. The selected filmmakers were chosen by an expert committee purely on merit, and the films that emerged have been nothing short of exceptional. We are also committed to creating space for gender minorities and people with disabilities in our cultural landscape,” affirmed Cherian.

A senior director, who preferred to be anonymous and did not want to be drawn into the controversy pointed out, “Adoor Gopalakrishnan himself was a major beneficiary of state and central support in the 1970s and ’80s. Films like Elippathayam, Mathilukal, and Kathapurushan were funded through NFDC grants, screened at state-sponsored festivals, and backed by public infrastructure. Today, when similar support reaches women or Dalit filmmakers, the narrative suddenly changes.”

“Why is it that when upper-caste men get state funds, it’s called culture but when others get it, it’s seen as compromise?” asked one young filmmaker, whose script has been selected under the SC/ST category. “We are not asking for charity. We’re asking for space,” said the filmmaker.

The response to Adoor’s comments reflects a larger shift in the cultural conversation. It’s not simply about opposing a legendary director, it’s about refusing to let the old structures define what merit looks like. And as filmmakers pointed out, merit, after all, is shaped by access but access has never been evenly distributed until now.

Political message

This is where Kerala’s film funding model becomes important, not just for the films it supports, but for the political message it sends, said filmmakers.

It recognises cinema as a public good, and public money as a tool for broadening participation. Whether or not each film recovers its cost is beside the point; what matters is that the door has been opened.

Scheme to continue

Amid this controversy, there’s also a quiet optimism over how the state plans to move forward. Officials have indicated that the scheme will continue, with a new round of applications expected later this year.

For now, these films may not have broken box-office records, but they’ve broken silences. In doing so, they’ve shifted the narrative, one that no longer accepts exclusion as default, or merit as something that belongs only to the privileged.