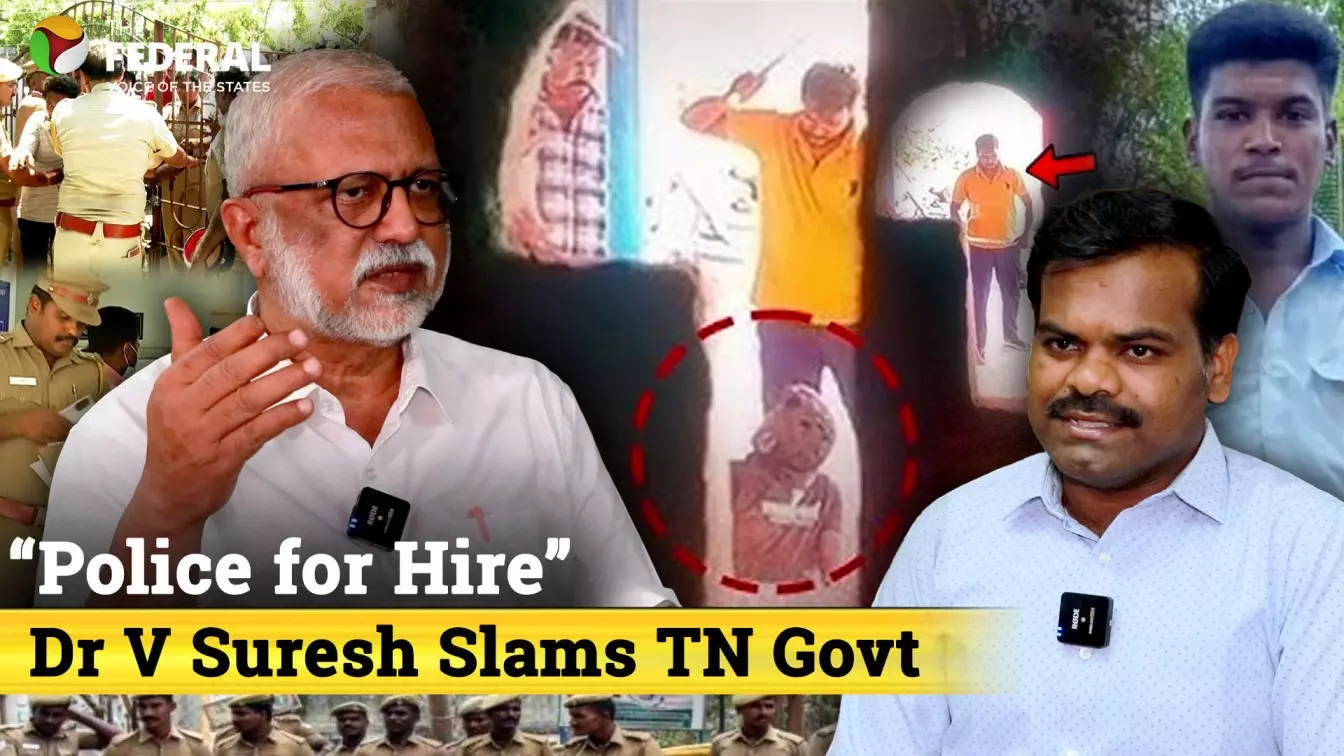

"Police for Hire"

TN custodial deaths: Human rights activist slams police-politician nexus

Dr V Suresh exposes how custodial deaths, caste bias, and political patronage plague Tamil Nadu policing. Can accountability ever be ensured?

Tamil Nadu’s record on custodial deaths has come under sharp scrutiny following recent cases like the Sivaganga incident. In this hard-hitting conversation with The Federal’s Mahalingam Ponnusamy, human rights lawyer Dr V Suresh lays bare the deep-rooted issues of caste, corruption, political collusion, and impunity within the state’s police force.

How do you see the state of policing in Tamil Nadu today, especially in light of recurring custodial deaths?

Tamil Nadu is a police state. The police are available for hire. Within the police itself, there is tremendous caste division and also political division. Unfortunately, senior IPS officers have sold their souls. They have removed their spine. Their commitment is available for a price. Obviously, the Chief Minister is responsible for the whole thing. What did the DMK do to curb the police menace in Tamil Nadu? We have examples of the CBI itself showing caste and various other prejudices. The bulk of custodial torture takes place in theft cases. The government has very beautifully silenced the victims.

The government dismantled special units after the Sathankulam and Sivaganga custodial deaths. What’s your take?

The primary issue with Tamil Nadu police is that they rule the state, irrespective of DMK or AIADMK. Barring a small number of honest officers, the bulk of the force is corrupt. There’s political corruption and corruption for money. In theft cases, police powers are misused at the behest of interested parties. We at PUCL have opposed the concept of ‘Friends of the Police’ for 25 years. It started with good intent but became a lawless force used for kattapanchayats and kangaroo courts. These people gain political patronage and make money, mediating civil disputes.

What about the lack of accountability in special units?

Special units operate without accountability. They take accused persons, grill them, and later disown responsibility. It happens under the cover of the police station. Officers must be held responsible. We had a young IPS officer who pulled out suspects’ teeth in Tirunelveli district. What happened to him? Nothing. There was an eyewash inquiry, and that’s it. Lower-level officers get punished. IPS officers protect themselves as a guild. If top officers stood firm, no torture would happen.

Could you elaborate on the role of caste and political divisions in the police force?

The police force is highly caste-based. Different regions have dominant castes: Thevars, Nadars, Vanniyars, Mudaliyars, Gounders. These communities wield economic and political power, controlling police and administration. There are also political divisions: officers known to be pro-DMK or pro-AIADMK don’t get proper postings if the other party is in power. IPS officers take an oath to the Constitution, but in practice, their loyalty is to themselves and their political masters, not the rule of law.

Where does accountability lie for custodial deaths?

Accountability starts with the station officer and superintendent of police. There is a concept called command responsibility: all officials in the hierarchy—IG, DIG, SP, DSP, circle inspectors, sub-inspectors—should be held responsible. Those who directly commit offences and those who fail to supervise should both be accountable. The Chief Minister is ultimately responsible for law and order, but blaming him for every incident dilutes and diverts the issue.

Tamil Nadu records 490 custodial deaths between 2017 and 2022. Yet, convictions are almost zero. Why?

That’s the tragedy. Even one custodial death is too many. Tamil Nadu had 490 deaths; comparing it with Uttar Pradesh’s 2,630 doesn’t justify it. Convictions are negligible because the system protects itself. Political executives enter into a quid pro quo with police: shield them in return for doing their political bidding.

How effective is the legal and rights mechanism, including the Human Rights Commission?

The State Human Rights Commission works in fits and starts. Barring a few exceptions, appointees are political beneficiaries. If they were proactive, Tamil Nadu wouldn’t be in this sorry state. Most custodial torture happens in theft cases. I have seen horrific cases—like Arun Kumar’s in 2006, where his fingers had to be amputated due to police torture. Despite High Court orders, no action has been taken even after all these years.

The government offers compensation to victims’ families. Is this enough?

Victims’ families deserve reparation and support. But giving compensation is used to silence them. The issue is accountability: ensuring FIRs are filed, arrests made, and investigations completed swiftly. The Ajith Kumar case is a test—will they act against all involved, including the IAS officer who allegedly interfered? Such people must be named and held accountable to set an example.

The case is handed to the CBI. Will that ensure justice?

Transferring to CBI is damage control. The CBI has shown biases in past cases like Kannagi Murugesan’s. We hope for balance, but experience tells us otherwise. The Chief Minister can’t escape responsibility by passing the case to the CBI. He must account for the rise in custodial crimes during his tenure.

The content above has been generated using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.