- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Eviction drives in Assam’s Golaghat leave migrant Muslim families pushed to a corner

Uprooted from Uriamghat, Muslim families settled by the state decades ago now find themselves labelled as ‘encroachers’; they watch their homes erased, their lives pushed into ghettoisation and isolation

Heartbroken and helpless, former neighbours at Uriamghat in Golaghat district of Upper Assam, 47-year-old Abbas Ali and 45-year-old Ruhul Amin — both victims of the ongoing eviction drives — bade a final farewell to their demolished homes on August 2, before setting out to find what lay ahead for their families. They are among the thousands of unfortunate residents whose houses...

Heartbroken and helpless, former neighbours at Uriamghat in Golaghat district of Upper Assam, 47-year-old Abbas Ali and 45-year-old Ruhul Amin — both victims of the ongoing eviction drives — bade a final farewell to their demolished homes on August 2, before setting out to find what lay ahead for their families. They are among the thousands of unfortunate residents whose houses were razed before the Supreme Court, on August 22, ordered an interim stay and an immediate halt to the eviction drives in Golaghat district.

A Supreme Court bench comprising Justices P.S. Narasimha and A.S. Chandurkar passed the order, bringing major relief to thousands of families who had already received eviction notices from the government. Now labelled as encroachers, both Ali and Amin belong to families that were settled in Uriamghat 40-45 years ago by the then Assam government to counter encroachments from groups and organisations in neighbouring Nagaland. Over the decades, these families built new lives there, facing every challenge that came their way. Before this resettlement, both Ali and Amin’s families had lived in Dhing, in the central Assam district of Nagaon.

Countering Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma and the ruling party’s narrative that they were encroachers who had occupied land in a Hindu-majority constituency to alter its demography, Ali and Amin recalled the stories they had grown up hearing from their fathers and other elders about repeated attempts by groups from neighbouring Nagaland to encroach upon Assam’s land and alter the state boundary.

“Our families, along with many others, were settled in Uriamghat by the Assam government in the late 1970s and early 1980s. They braved threats from various groups from Nagaland who tried to occupy Assam’s land. Now it’s heartbreaking to hear allegations that we encroached on this land with ulterior motives,” said Ali.

“We have seen ministers making speeches, claiming that we came from Muslim-majority constituencies to change the demography here. This is a lie. Sadly, common people now tell us to go and live in a Muslim-majority area,” he added. “This is deeply painful and unfair. We have documents proving that we were settled in Uriamghat by the government 40–45 years ago, and that we never encroached on the forests,” Ali said.

Evicted people from Uriamghat reaching Dhing. As thousands face demolitions and dislocation, victims highlight broken promises of resettlement, while experts warn of ghettoisation, demographic fault lines, and divisive politics. Photo: Special arrangement

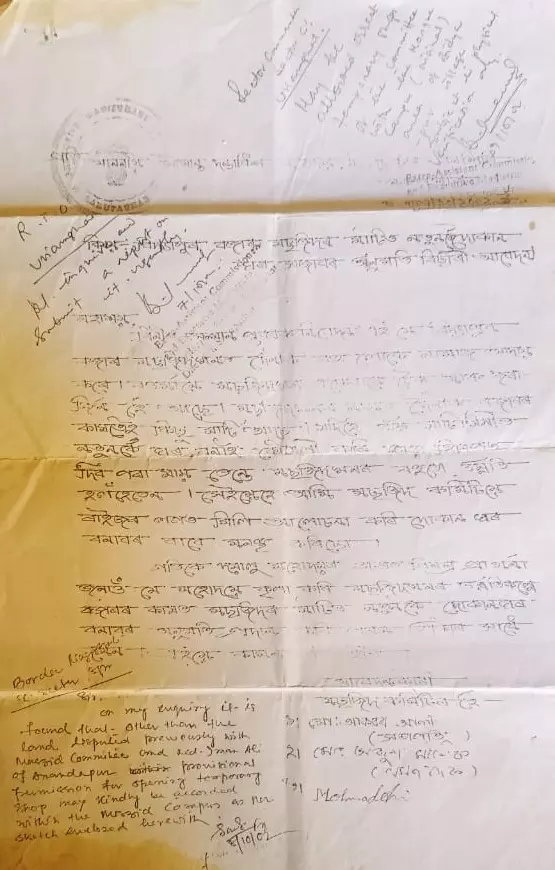

Presenting his case, Abbas Ali produced a file containing government documents, signed and sealed by officials in the late 1970s and early 1980s, granting families permission to settle in Uriamghat. With no other options left, Ali and Amin — like thousands of others — moved to new places to rebuild their lives. According to them, the eight-hour truck journey from Uriamghat to Dhing in Nagaon district, with all their belongings, felt like a journey of a lifetime.

“But a few days later, I realised I was not only betrayed by the state government but also outrightly disowned by my friends and relatives in the district where my family had lived before moving here,” said Amin.

“I came to Dhing with my family and belongings, but the moment we unloaded them, people — even from within the Muslim community — told us we were not welcome and asked us to leave. It was a huge shock and I felt shattered,” Amin added, explaining that they were told land resources were already under pressure due to erosion, making it difficult to accommodate new families.

Also read: How DDA’s slum rehabilitation flats failed the poor, displaced families in Delhi

Abbas Ali, however, was somewhat luckier. His relatives offered him temporary shelter and space to build a makeshift house until his situation stabilises. “After all these years, we have lost our ancestral land in undivided Nagaon district, which has since been divided among our extended family. Now we are left to live in a small makeshift house in Dhing, wondering how to move forward,” Ali said.

Similar is the plight of 42-year-old Ruhul Hussain, who now lives across the Brahmaputra on its north bank, in Assam’s Lakhimpur district. Hussain said he had lived his whole life in Phukondoli village, which falls under the Naoboicha revenue circle in Lakhimpur. He and his family were engaged in the fishery business and earned their livelihood from it.

“About four decades ago, we lost our land and house to erosion by the Brahmaputra river. Since then, our family has been living here. We built our house and raised a family — me, my wife, and our three children,” Hussain said.

“We received a notice weeks before the eviction drive, stating that we had occupied village grazing land and were asked to vacate. We pleaded with government officials, explaining that we had lived here for decades, but our pleas were ignored,” he added.

Evicted people from Uriamghat in Assam's Golaghat. Photo: Special arrangement

Hussain’s family was among the 114 affected by the government’s eviction drive on August 7. Later, he and several others filed a petition at the Gauhati High Court, hoping for relief, but none came.

Advocates representing eviction victims at the High Court welcomed the interim stay ordered by the Supreme Court on eviction drives in Golaghat district. However, they also cautioned that not much should be expected from the judiciary.

Also read: How Hindutva’s war on religious conversion exposes BJP’s Christian dilemma in Kerala

“As per Assam’s land laws, the government can evict people from government land, forest land, and grazing land at any time, and without paying compensation. This is why those who have filed petitions are unlikely to receive much relief,” said Krishna Gogoi, an advocate practising at the Gauhati High Court who has handled several land cases.

Gogoi explained that unless the government amends existing laws, eviction drives are likely to continue. “The only way these laws can change is through sustained public pressure on the government,” Gogoi added.

Sociologists have raised concerns over the issue of ghettoization, warning that it could create major fault lines in the state. “If this is merely a narrative created by the government with an eye on next year’s elections, aimed at garnering attention and votes, then perhaps the damage done could be reversible in the short term. But if the government pushes this agenda for the long term, the consequences will be severe and very difficult to undo,” said a professor of Sociology at a Central Government Institute, who requested anonymity.

The professor added that such measures could give rise to conflict-driven politics in the state. “Assam’s demography and society are mixed, interdependent, and to a certain extent, delicate. These kinds of fault lines will irreparably damage that balance,” he cautioned.

Government orders issued by officials decades back permitting Muslim families to settle at Uriamghat. Photo: Special arrangement

Civil society groups have come down heavily on Assam Chief Minister, urging him to refrain from making statements that could trigger communal divisions. “The Chief Minister has introduced this new narrative of constituencies for Muslims and constituencies for non-Muslims. This is a highly divisive approach and could have long-term consequences for the state,” said Hafiz Rashid Choudhury, a senior advocate associated with Assam Civil Society, a group that has long been advocating for communal harmony in the state.

Responding to the Chief Minister’s claim that migration from Muslim-majority constituencies into areas with fewer Muslims was a deliberate attempt to alter demographics and encroach on land for voter list manipulation, Choudhury countered: “When someone shifts to a new place and settles there, it is only natural for that person to apply to be included in the voter list and thereby become a voter in that constituency.”

Keeping the pot boiling over the recent eviction drives in Assam, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, in his Independence Day speech, invoked the threat of demographic changes in the state as real and reiterated that “evictions will NOT STOP.”

“All unauthorized occupations of VGR (Village Grazing Reserve), PGR (Professional Grazing Reserve), Satras, Naamghars, forest land, and other public areas will be cleared in a phased manner. With the completion of the Uriamghat eviction drive, the total area of land freed from encroachments across the state will exceed 1.5 lakh bighas,” the Assam Chief Minister said.

According to Central government data, as of March 2024, 3,62,082.62 hectares of forest land in Assam remain under encroachment.