- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Assam’s visually impaired keep learning to read and write against all odds

With scarce Braille textbooks, high costs, and little government support, Assam’s blind battles systemic neglect, even as a few writers, activists, and schools strive to open the world of reading and learning

For decades, the lives of the visually impaired people in Assam have remained largely unchanged. So, when author and musician Anjali Mahanta set out to tell the inspiring story of Kamala Barua, Northeast India’s first visually impaired graduate, it was momentous. But Mahanta took it a step further when she insisted on getting the book on this daughter of Assam published in Braille....

For decades, the lives of the visually impaired people in Assam have remained largely unchanged. So, when author and musician Anjali Mahanta set out to tell the inspiring story of Kamala Barua, Northeast India’s first visually impaired graduate, it was momentous. But Mahanta took it a step further when she insisted on getting the book on this daughter of Assam published in Braille.

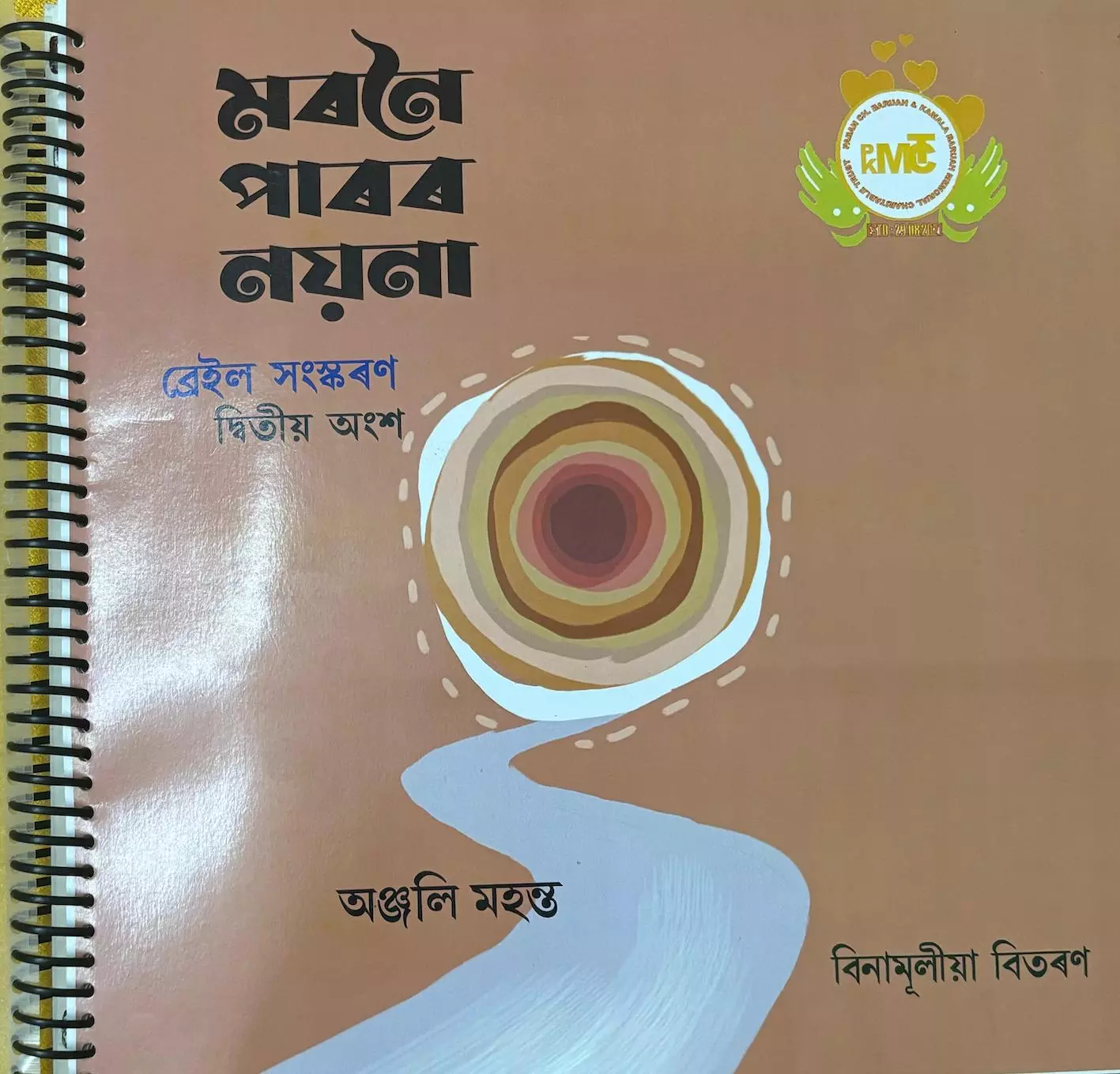

In a region, where books in Braille are rare, this was a meaningful gesture. The Assamese book, Moronoi Parar Noyona (Noyona, by the Moronoi Riverside), released last year, became the first fiction to be read in Braille by visually impaired persons in Assam and, more importantly, in their mother tongue.

Mahanta intensely admired Barua, seeing her as ‘a pioneering woman of Assam’. After all, way back in 1955, in a state where there was no infrastructure or opportunities for the visually disabled, Barua was among the first few students to be admitted to Srimanta Shankar Mission Blind School in Nagaon, one of the first schools for the visually impaired.

In a chat with The Federal, Mahanta explains why she decided to write a book on Barua. “Despite facing numerous hardships and struggles, Barua baideu (elder sister) never gave up. After completing her schooling, she enrolled in college and graduated and became the first visually impaired woman to earn a college degree in the north-east region,” Mahanta says.

When Barua decided to pursue her higher education at the Nagaon Girls' College, the first roadblock she encountered was that Braille textbooks were not available. She overcame this by getting her friends and family members to read textbooks for her, and she wrote them in Braille.

Barua then worked as a schoolteacher at her alma mater and taught hundreds of students to be courageous and self-sufficient. “She was an inspiration for many and went on to receive several awards, including the President’s Award,” Mahanta says. The author also knew Barua baideu (elder sister), as they hailed from the same place, Nagaon.

The cover of the novel, Moronoi Parar Noyona (Noyona, by the Moronoi Riverside). It is based on Kamala Barua's life.

“She had typhoid when she was a toddler. This led to rare complications and she lost her vision. She died in 2009 when she was 60,” shares Mahanta, adding that it was only when she started researching her life, more than a decade after her death, that she truly ‘discovered’ more about this changemaker.

After years of research, she finally wrote a novel about Barua instead of a biography, “to aptly capture the emotions and mental state of visually impaired individuals.”

Also read: Ayyappan Theeyattu, Kerala’s ritualistic theatre form, opens its doors to a female artist

What’s interesting is that Mahanta spoke to several visually impaired people to get a better understanding of the inner world of visually impaired people. The author, who has earlier written two novels, Maya and Khuj, shares what she learnt about their world.

“I found that these intelligent, brave and philosophical people live in a beautiful world. They don’t need anyone’s pity. Some of them told me that being blind is better than being a sighted person. Their sense of understanding of the world is accurate and profound,” points out Mahanta.

Determined to ensure that her book can be easily accessed by the visually impaired, she simultaneously published it in standard print and Braille. “I was determined that this book had to be in Braille. Until now, besides educational materials, there have been no Braille books in Assamese. So, I printed around 50 copies of the novel,” affirms Mahanta.

Publishing books in Braille is expensive. Bharat R Joshi, deputy director of Gujarat-based NGO, The Blind People’s Association (BPA), tells The Federal, “The cost of printing a Braille page is twice that of a standard one. Moreover, it is voluminous. Every regular book printed in Braille usually comes in two to three volumes.” The Braille edition of Moronoi Parar Noyona is in two volumes.

The prohibitive cost of publishing books in Braille means textbooks and dictionaries, for schools and higher education are also scarce. The lack of Braille textbooks for visually impaired students are hampering education prospects of blind children, admits Gobin Sonar, a visually impaired activist from Assam’s Dibrugarh. The 33-year-old completed his graduation from Tingkhong College, Dibrugarh, a college for sighted people.

Explaining his own challenges to pursue a degree, Sonar says, “All the blind students who completed their college education in Assam studied in colleges for sighted people, as there are no higher educational institutions for us. It was with great difficulty that I finished my college education. First, there were no textbooks in Braille. I used to record the lectures in classrooms. Some of my friends read out books, and I would write them in Braille.”

Kamala Barua, Northeast India’s first visually impaired graduate.

Schools in Assam also struggle with lack of books in Braille. As the secretary of the Upper Assam Blind Union, Sonar points out that his organisation had repeatedly petitioned the government to provide blind schools with Braille textbooks in all subjects.

“The children don’t have access to textbooks in all subjects. Some schools have Mathematics Braille textbooks but no English ones. In the Guwahati Blind School, students of classes 11 and 12 don’t have Braille textbooks. They can’t study without books,” he says sadly.

What’s tragic is that most of the visually impaired people in Assam are born in poor families, where the parents are illiterate and cannot afford to send their wards to schools, adds Sonar.

Naresh Joshi, the head administrator of Moran Blind School in Assam, admits that technology can be leveraged to learn and disseminate knowledge among visually impaired students in the state. “Since textbooks in Braille are not available in Assam’s blind schools, to read a fiction or non-curriculum book is beyond the imagination of a visually impaired person in the state,” he adds.

Also read: How Purulia’s Chhau dance is changing, and what it’s losing along the way

Moran Blind School, a residential institution, has 65 students from Class 1 to Class 10. It provides free education and depends on donations from individuals and corporations to cover expenses. These children come from nearby tea gardens (Moran town in Dibrugarh district is surrounded by lush green tea plantations) and belong to the Adivasi community, who are poor.

“The parents of the visually impaired work in tea gardens as labourers and earn around Rs 250 (some even less) daily. So, very often, their children can’t pursue education after they finish class 10,” he says. And, shares that some families never come back to take their children home from the blind school.

“A visually impaired person is still considered a liability here. It is with great difficulty that the school is functioning, as help from the government is almost nil,” adds the head administrator of the Moran Blind School.

The school has been imparting education in English medium instead of Assamese for the last 10 years. “The idea is to equip and encourage children to move outside the state to pursue higher education after class 10. If they know English, they don’t have to struggle with a new language in a new place,” says Joshi. At this school, they teach the children everything from orientation on mobility and blind friendly spaces to toilet manners to make them independent.

Prabhakar Upadhyay, an activist from Assam’s Kaliabor, and Sushila Pegu, a disability rights activist.

Prabhakar Upadhyay, 42, an activist from Assam’s Kaliabor who lost his vision due to hereditary disease Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP), says the condition of people with visual impairment in Assam is pathetic.

“Most schools for blind children are only in name. There are no textbooks, nor medical facilities to attend to the needs of students. Those who are born in poor families have no life, as they are forced to live inside their homes. They have no skills and can’t earn a living. Their families treat them as a burden,” stresses Upadhyay.

There are an estimated 4.95 million blind persons and 70 million vision-impaired persons in India, according to the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Notably, in a 2020-21 report of the National Programme for Control of Blindness, Assam, it was highlighted that the prevalence of blindness in Assam is higher (3.03 per cent) than the national average (1.99 per cent).

Also read: Mysuru Dasara may see Abhimanyu’s last walk as Golden Howdah bearer this year

“Data shows that India has only 1 per cent Braille literacy rate. That leaves most of the visually impaired people illiterate. Technology like Non-Visual Desktop Access (NVDA) or Job Access with Speech (JAWS) software can change the learning experience for people with disabilities. But technology is expensive for most to use,” says Upadhyay.

In Gujarat, the NGO BPA used technology to work around publishing expensive books in Braille. The NGO has been working on a project called Dhwani, where inmates of the Sabarmati Central Jail in Ahmedabad have recorded around 6,000 audiobooks in English, Hindi and Gujarati for visually impaired people.

“Earlier, we were printing Braille books. Now, we are making the best use of technology to make learning inclusive and more affordable,” says Joshi, adding that the project is helping to empower two groups: the jail inmates and the visually impaired.

“All the jail inmates, who are a part of our project, are paid for their work. Those who have completed their prison time too have taken to recording audiobooks as a source of income,” he says.

The government is also contributing to provide facilities for the visually impaired. The National Braille Library, run by the National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Visual Impairment (Divyangjan) (NIEPVD) in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, has approximately 1,33,265 volumes on its shelves comprising over 16,681 titles. (The NIEPVD falls under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment).

Author and musician Anjali Mahanta.

Other organisations, like the Gujarat-based BPA, also publish, catalogue and distribute reading and audio materials to the visually impaired. “But at the grassroots, children are struggling to finish their school education,” rues Sushila Pegu, 32, a disability rights activist. Along with her husband Upadhyay, Pegu, who lost her sight when she was only a few months old, has started an NGO called Drishtikon.

Pegu was born in Assam’s Majuli. She did her schooling at Jorhat Blind School, Jorhat and finished her graduation from Ujani Majuli Kherkatia College, Majuli. She was working for EnAble India, an NGO for persons with disabilities in Bengaluru, for three years but in 2021 she returned home to Assam to work for blind people. They needed her more.

“We have a lot of work to do to empower blind people. With our NGO Drishtikon, we are trying to bring some change in the lives of the most neglected community in Assam. Education and jobs are the only two ways to make the lives of blind people better,” states Pegu, who is a graduate like Barua.

Each of these NGOs are striving to enhance the quality of the lives of the visually impaired in Assam, many of whom, lacking access to education or skills, often find themselves isolated and locked up in their own misery.