- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Scrolls worship to foreign tie-ups, how Kolkata’s Durga Puja celebrations are blending cultural traditions

Since being inscribed in UNESCO's ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ list in 2021, the festival has emerged as a platform for international partnerships, exemplifying Durga Puja’s evolution, shaped by a continuous amalgamation of cultures and adaptation to the times

Juliette Barthelemy’s eyes light up as she talks of her first-ever Durga Puja in West Bengal. “It is a completely new experience for me. Had I not come to Bengal, I would have never understood the passion people here have for Durga Puja,” said the French national. She added: I am helping decorate the pandal, inviting people [to visit the puja]…. it has all been wonderful. I will...

Juliette Barthelemy’s eyes light up as she talks of her first-ever Durga Puja in West Bengal. “It is a completely new experience for me. Had I not come to Bengal, I would have never understood the passion people here have for Durga Puja,” said the French national. She added: I am helping decorate the pandal, inviting people [to visit the puja]…. it has all been wonderful. I will offer pushpanjali [flower offerings to deity], do the dhunuchi naach [dancing with a clay pot holding burning incense, part of Durga Puja rituals] and take part in the visarjan [idol immersion at the end of the festival].”

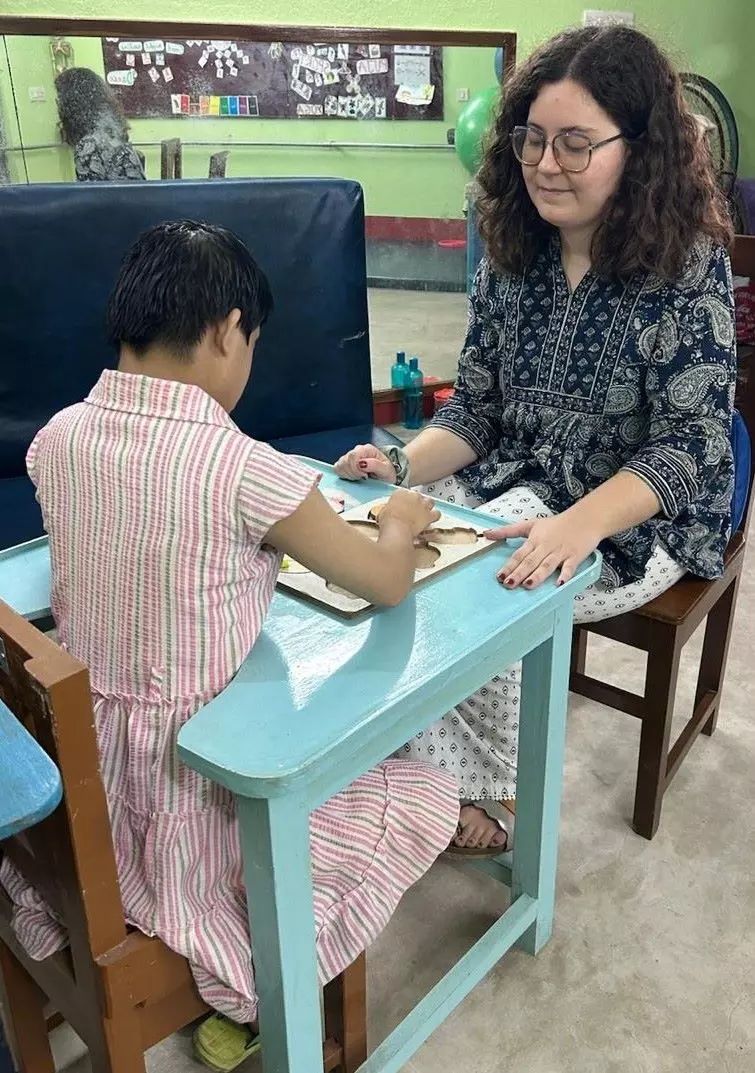

The annual five-day Durga Puja celebration in Bengal started on September 28 this year. For about a fortnight preceding the festival, Juliette, an occupational therapist, and her friend Timothee Chopin, a neuropsychologist, had been collaborating with residents of Asha Bhavan Centre in Uluberia, on the outskirts of Kolkata, to prepare for this year’s celebration at the centre.

Asha Bhavan, run by the Persons With Disabilities (PWD) Forum, advocates for the rights of children, women, and people with disabilities. Their theme for this year’s Durga Puja celebration is ‘Green Bengal’.

From crafting eco-friendly decor with the children to going door-to-door inviting guests, the two French women embraced every part of the puja process. “They’ve become one of us,” said forum secretary Putul Maity.

French national Juliette Barthelemy at the Asha Bhavan Centre on the outskirts of Kolkata, run by the Persons With Disabilities (PWD) Forum, where she is helping organise this years Durga Puja celebration. Photo by Jayanta Shaw

Barthelemy and Chopin say their curiosity about Durga Puja was sparked four years ago, when UNESCO, in 2021, inscribed Kolkata’s Durga Puja on its list of ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’. On its website, UNESCO mentions that the celebration is “characterised by large-scale installations and pavilions in urban areas”.

Increasingly in Kolkata, Durga Puja is emerging as a platform for professional cross-cultural partnerships, with foreign nationals collaborating artistically with locals.

At the Hatibagan Sarbojanin Puja in north Kolkata, one of the city’s most visited pandals, French artist Thomas Henriot has teamed up with local artist Tapas Datta to create a striking 22ft by 7ft mural. The piece, depicting the ghats of the Ganga, blends Henriot’s expressive ink work with Datta’s traditional Indian techniques, resulting in a compelling confluence of two artistic languages that honours both heritage and innovation.

This is not the first example of such creative synergy in Kolkata’s ever-evolving Puja landscape. Last year, Irish artists Lisa Sweeney and Richard Babington collaborated with local artist Sanjib Saha to design a tableau that reimagined goddess Durga alongside the Irish deity Danu, at the Behala Nutan Dal Puja to celebrate 75 years of India-Ireland diplomatic ties.

These collaborations exemplify Durga Puja’s extraordinary journey of evolution, shaped by a continuous amalgamation of cultures over time, adapting to the socio-economic realities and cultural relevance of its era.

Also read: How West Bengal is pushing back against BJP’s Bangladeshi infiltration narrative

But were Durga Puja celebrations always the big-budget, grand, artistic spectacle that it is today?

The modern concept of theme-based pujas in Kolkata — presenting a certain art form, social issue, news event, iconic landmark or pop-culture milestone in pandal construction and decor — can be traced back to 1959, say those in the puja organising circuit. That year, the Jagat Mukherjee Park Durga Puja committee in north Kolkata introduced an innovative approach to pandal decoration by hiring a young artist, Ashok Gupta, to adorn their marquee with elaborate murals, recalled Apurba Mazumdar, a renowned Durga Puja pandal director, who has been conceptualising and designing themed marquees for nearly three decades.

According to him, this marked a significant turning point in the visual and cultural language of Durga Puja celebrations.

"The earliest recorded history of Durga Puja in Bengal dates back to the Pala Empire (8th to 12th century CE), a period known for its strong patronage of Vajrayana Buddhism, when goddess worship was already widespread within Buddhist tantric traditions. Archaeological findings from the Pala period, such as sculptures preserved in the Indian Museum in Kolkata, depict Durga in her Mahishasuramardini form, slaying the buffalo demon, a motif central to Durga worship [in Bengal]. At that time, idols were typically carved from black stone,” said Gautam Sengupta, a retired professor of history.

He added: “Depictions of Durga as Mahishasuramardini also appear prominently in Pallava-period rock-cut temples at Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu, dating back to the late 7th century CE. It is possible that the Pala rulers adopted or were influenced by the tradition of Mahishasuramardini worship from the southern kingdoms, with whom they maintained a strong cultural and political connection.”

Incidentally, said Gupta, during the Pala period, Mahishasuramardini was worshipped as Chandi, suggesting another potential cross-cultural influence, observing that the patron deity of the Pala dynasty was the Buddhist goddess Cundi, whose name bears a phonetic resemblance to Chandi.

French national Timothee Chopin at the Asha Bhavan Centre. Photo by Jayanta Shaw

According to the Hindu scripture Markandeya Purana, Durga Puja was originally celebrated in spring. During the 14th or 15th century, while translating the Sanskrit Ramayana into Bengali, Krittibas Ojha departed from the original text to craft the story of the Hindu deity Rama’s invocation of the Goddess out of season, termed Akal Bodhan in Bengali, prior to his battle with Ravana in autumn. The original Sanskrit version of the epic describes Rama invoking the sun god Surya, not Durga, for victory in his battle against Ravana. Vijaya Dashami — which follows the nine-day Navratri celebration across India, coinciding with the Durga Puja festival in Bengal — is celebrated in many traditions as the day Rama defeated Ravana, though Bengalis celebrate it as the day Goddess Durga defeated the demon Mahisasura.

While there may be debate over what inspired Ojha to craft this narrative, it undeniably created a powerful synthesis between the Vaishnava tradition centred on Rama and the Shakta tradition devoted to Durga, fostering greater coexistence between these two Hindu sects in Bengal.

“The Bengali autumnal celebration of Durga Puja, as observed today, began gaining prominence around the 17th century,” observed Sengupta.

Anasua Roychowdhury, a professor of Bengali literature at Rammohan College in Kolkata, believes that the shifting of the Bengali festive season from spring to autumn was a pragmatic decision, as the latter being the harvest season, was far more conducive to celebrations. “Additionally, spring in Bengal was, in those days, often marked by deadly smallpox outbreaks,” she said.

The book Murshidabad: Forgotten Capital of Bengal, edited by Neeta Das and Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, mentions how the city was ravaged by a severe smallpox epidemic in 1770, which is believed to have claimed the lives of around 63,000 people.

Also read: How Hindutva’s war on religious conversion exposes BJP’s Christian dilemma in Kerala

The earliest written record of Durga Puja being celebrated in autumn — during the months of September to November according to the Gregorian calendar — in Bengal dates back to the reign of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. “At this time, Jahangir was strengthening Hindu zamindars as a political counterbalance to the fractious nawabs of Bengal Subah,” Sengupta pointed out.

One such ally, Raja Kansa Narayan of Taherpur (in present-day Rajshahi, Bangladesh), famously organised the first grand autumnal Durga Puja, or Saradiya Durga Utsav, in Bengal in 1610. This set a precedent that other zamindars loyal to the empire, including Bhabananda Majumdar of Nadia, soon followed.

A 125-feet tall Durga idol being set up at a celebration in Ranaghat, West Bengal, ahead of the ongoing festival. Photo by Jayanta Shaw

In stark contrast to the royal celebrations of the Goddess is the tradition of the humble 'Pata Durga' — the worship of the Goddess painted on cloth or scrolls; Pata means fabric in Bengali — highlighting the adaptability of Durga Puja to suit popular needs.

The Pata Durga worship, often serving as an alternative or complement to the veneration of the more elaborate three-dimensional clay deity, appears to have existed in many rural areas before the widespread use of sculpted idols, said Bijan Kumar Mondal, former curator of Gurusaday Museum, a Kolkata-based museum dedicated to the preservation of folk arts and crafts. The museum houses 60 'Pata Durga' paintings collected from various parts of Bengal.

“These intricate artworks are typically created by the patua or chitrakar [rural or folk artist] communities of Bengal, and the tradition evolved as a specialised branch of the broader Patachitra [scroll painting] art form," Mandal said.

For the paintings, cloth used to be treated with clay and glue to create a smooth surface. Natural dyes derived from plants, red ochres, limes and charcoal among others, were used.

“The designs were bold, characterised by flat perspectives, vivid reds, yellows, and blacks, and intricate line work. Beyond a single depiction of the deity, this detailed art form often illustrates the Mahishasuramardini narrative, portraying Durga’s triumph over evil in a portable and visually compelling storytelling tradition," he mentioned.

Religious scholars suggest that these painted representations were especially common during times of economic hardship or in households lacking access to skilled sculptors or the means to afford an idol, highlighting the festival’s adaptable and inclusive nature.

“In parts of Birbhum, Bankura, and West Midnapore, the tradition of worshipping Durga through pata paintings actually predates the use of sculpted clay idols,” said Janak Ram Acharya, a religious scholar and priest from Sendra village in Bankura. “The kind of clay needed for idol-making wasn’t readily available in these areas. On the other hand, patachitra was already a well-established art form, so it was far more practical to worship the Goddess in painted form on cloth or scrolls.

“Moreover, the concept of immersion wasn’t widely practiced back then, so preserving the deity was important,” he added. “In that sense, the patachitra form was more suitable than a clay idol, which is meant to be temporary.”

Also read: Kolhapuri Saaj: How this handcrafted gold necklace keeps a city’s heritage alive

A few families still refrain from worshipping Durga in clay form. The Gupta family of Sendra in Bankura is one such example. “Since the practice of the patachitra art form has become rare, the family has been worshipping Durga in a photo frame ever since their original Pata Durga was damaged about ten years ago,” said Janak Ram Acharya, who has been serving as the family’s presiding priest for the past 50 years.

While patachitra and sara art (Bengali tradition of shallow clay dishes being painted with religious themes, much like patachitra) have already, over the years, made their way to the decor of big-ticket Durga Puja pandals in Kolkata, the mainstreaming of 'Pata Durga' worship will require more than such a token nod. That it continues to survive and be cherished in the age of grand marquee celebrations, however, is a testament to the rich cultural diversity of this festival.