- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

The fungi that helps cook delicious meals from food waste

Alchemist, a 'holistic' restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, is unlike the others. There is no opportunity for telephone table reservations, and tickets for admittance are sold online three months in advance, demonstrating its popularity and client appeal. 'Just as the ancient alchemists sought to fuse philosophy, natural science, religion, and the arts to create a new understanding of the...

Alchemist, a 'holistic' restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, is unlike the others. There is no opportunity for telephone table reservations, and tickets for admittance are sold online three months in advance, demonstrating its popularity and client appeal. 'Just as the ancient alchemists sought to fuse philosophy, natural science, religion, and the arts to create a new understanding of the world order', Rasmus Munk, head chef and co-owner of the restaurant, says that the holistic dining at Alchemist, 'draws upon elements from the world of gastronomy, theatre, and art, as well as science, technology, and design, to create an all-encompassing and dramaturgically driven sensory experience'.

We are appalled by a piece of bread or a slice of vegetable with fungal mould and immediately trash it, but astoundingly, the current craze on the Alchemist's menu is a dessert named 'intermedia'. It is a solidified rice custard made with orange-coloured rice intentionally inoculated with a fungal mould. True to its boast, the fungi-infused dessert results from an amalgam of modern science and classic culinary techniques.

Fungi in food

Fungi, a kingdom of life that includes yeasts, moulds, smuts, and rusts, are used in cuisines worldwide, much like plants, animals, and insects. The best-known example is mushrooms. Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sometimes known as 'brewer's yeast’, is a unicellular fungus that ferments bread, beer, wine, and cheese. The highly coveted blue cheese is made from one kind of Penicillium, a fungus. Miso, soy sauce, and sake are fermented foods derived from the multicellular fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Bacillus pumilus is a Gram-positive, aerobic, spore-forming fungus found in soil used to make probiotics for humans and animals.

Neurospora mold grown on tomato pomace. It taste like a toasted bread with cheddar cheese on top.

In Indian cuisine, Parmotrema perlatum, also known as Pathar Ke Phool, Dagad Phool, or Kalpasi, is a kind of lichen with a symbiotic relationship with the fungus. It is a vital ingredient in garam masala and the secret behind the distinctive flavour of authentic Chettinad cuisine. When sautéed in fat, it gives off a smoky, woody, and earthy aroma.

Fusion

Like the meal he helped develop, Vayu Hill-Maini's life too is a fusion. He is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Bioengineering at Stanford University in California. Born and raised in Stockholm, Sweden, to a Cuban-Norwegian father and a woman whose parents were from Kenya's Indian diaspora, his family was a melting pot. His Indian mother gave culinary workshops in their flat, introducing Swedes to Indian flavours and cooking traditions.

With East, West, North, and South meeting and melting, the house where he grew up was naturally filled with various smells and aromas from every corner of the world. "With most of the family scattered across the world, the kitchen became a window to my rich cultural heritage," says Hill-Maini. In his multicultural upbringing, he developed an early interest in cuisine. "I grew up in a kitchen. There are many photos of me running around with kitchen knives and standing by the stove at the age of two," he adds. With species and condiments from around the world in the kitchen cabinet, "I discovered many tools for creating unexpected flavours and sensations; none was more powerful than the science I learnt in school," he adds.

“Cooking and science have remained my twin passions ever since,” Hill-Maini says.

Kitchen science

Being trained in numerous gourmet institutions, including Basque Culinary Centre, Fundación Alicia, The Cultured Pickled Shop, and Michelin-star restaurants Alchemist and Blue Hill at Stone Barns, Vayu Hill-Maini travelled from Sweden to the United States to work as a chef in restaurants. Cooking meals for gourmet clientele, he discovered that a molecular understanding of cooking boosted flavour profiles, stabilised solutions, and increased enjoyment. His interests in cooking and science propelled him to explore culinary science.

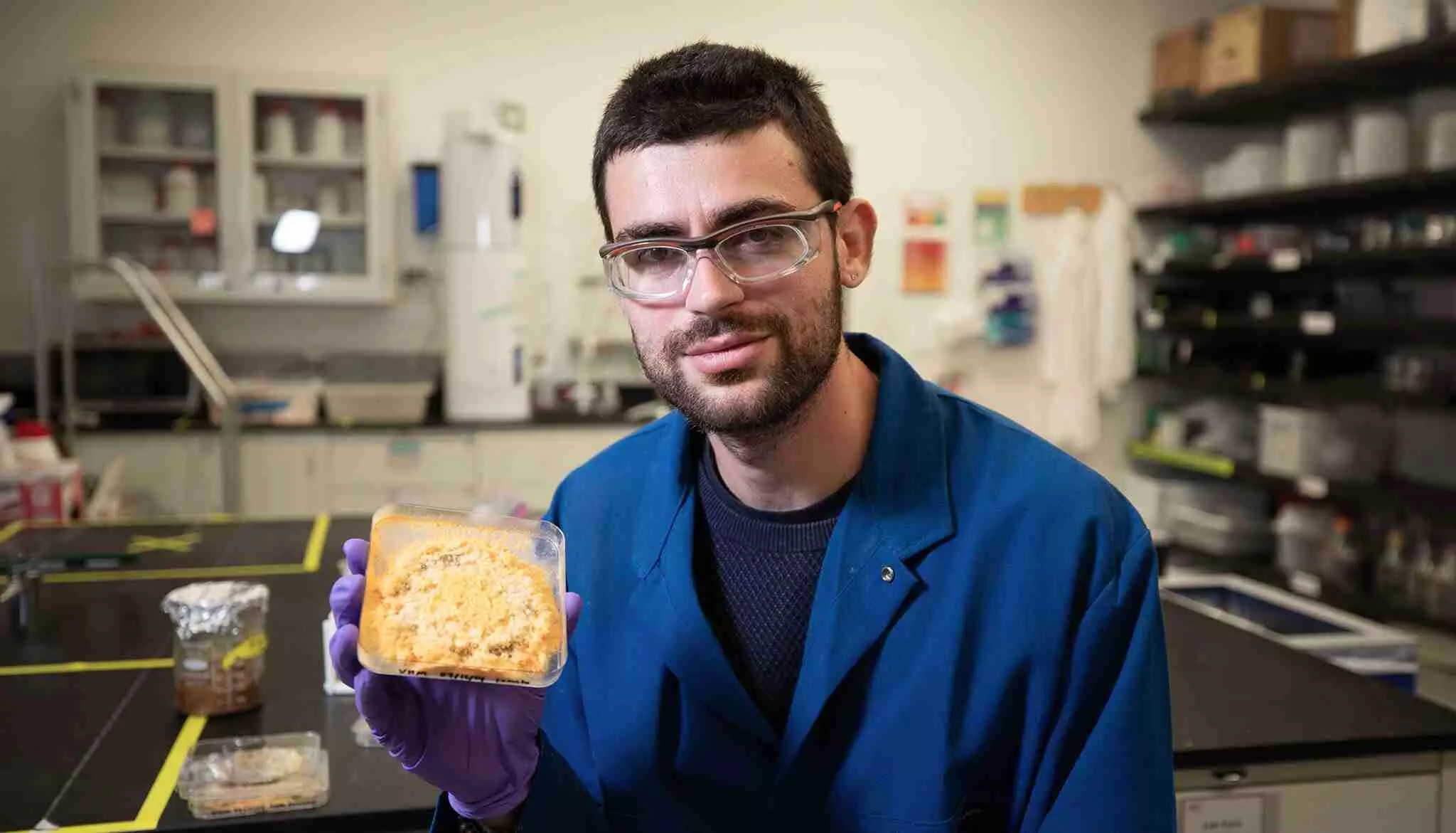

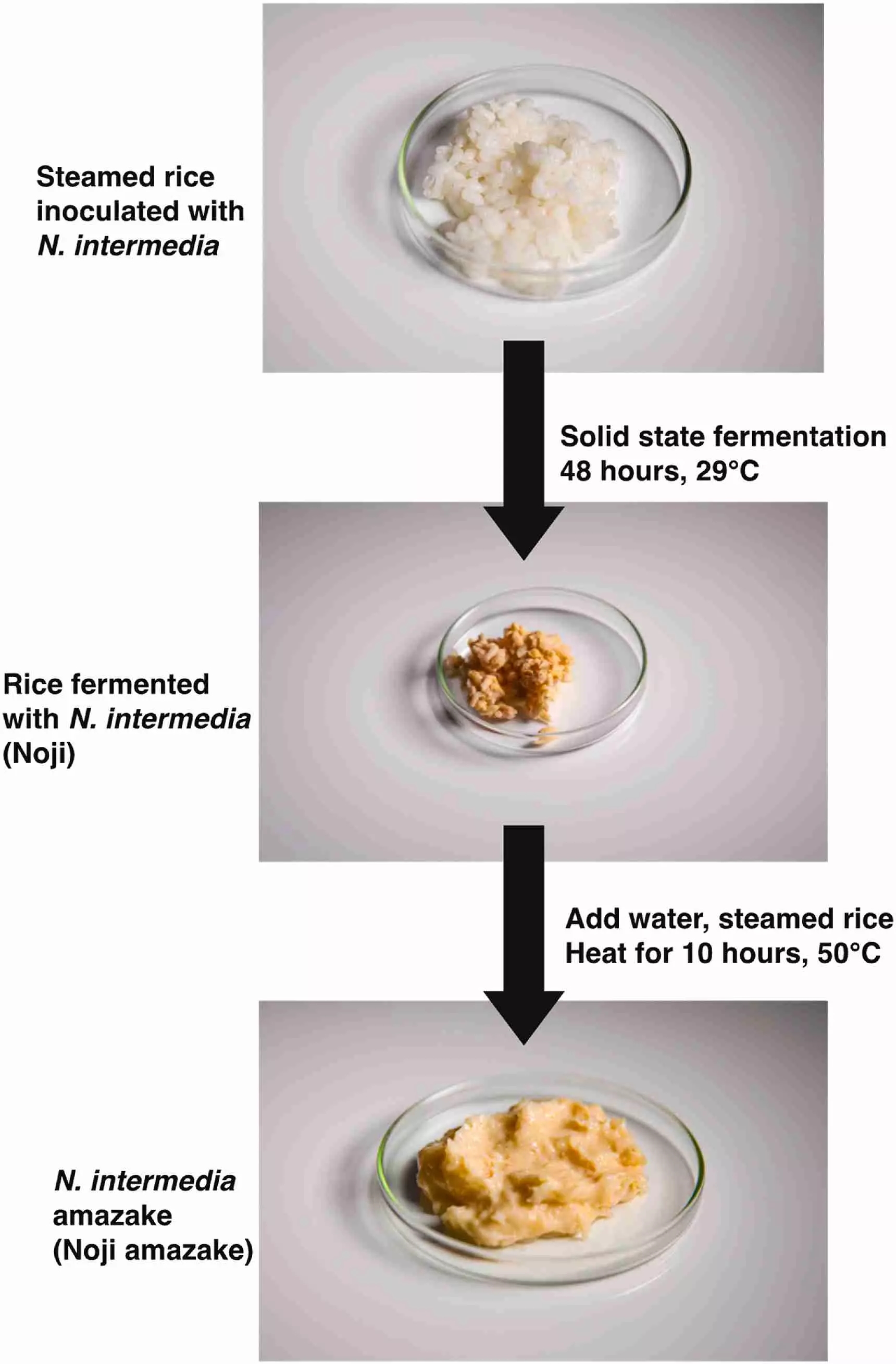

The process of preparing inoculated rice with Neurospora fungi.

Hill-Maini enrolled at Harvard University in 2020 to pursue a PhD in biochemistry. He investigated how gut microorganisms change the chemicals we consume, including food. After earning his degree, he joined Prof. Jay Keasling's group as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley.

Indonesian traditional food

As a chef and conscientious citizen, Hill-Maini sought to solve the problem of food waste. "Our food system is very inefficient. A third or so of all food that's produced in the US alone is wasted, and it isn't just eggshells in your trash. It's on an industrial scale," said Hill-Maini in a press statement. "What happens to all the grain that was involved in the brewing process, all the oats that didn't make it into the oat milk, the soybeans that didn't make it into the soy milk? It's thrown out." The loss and waste of food accounts for approximately half of total greenhouse gas emissions caused by the food system on a global level.

During his restaurant days, his Indonesian colleagues introduced him to oncom (pronounced ahn' cham), a classic Sundanese dish consumed by one of the main ethnic groups of western Java, Indonesia. Oncom, which has a spongy texture and tastes like grated cheddar on toasted bread, is made by fermenting waste from soymilk production or discarded peanut press cake using an edible fungus called Neurospora intermedia. It can be eaten raw or lightly cooked.

Microorganisms convert grain into bread, milk into blue cheese, and soybeans into soy sauce and miso, but the mouthwatering oncom is unique because it is made from food waste.

Hill-Maini believed the humble Neurospora intermedia may help him handle sustainability challenges and enable gastronomic creativity. For his postdoctoral research on Neurospora intermedia for food processing, he collaborated with his former coworkers, a team of chefs at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, a Michelin two-star restaurant in Pocantico Hills, New York, and Rasmus Munk at Amsterdam.

Genetics of Neurospora intermedia

Hill-Maini gathered and tested 10 authentic oncom samples from West Java. Oddly, he discovered that the fungus responsible for red oncom generated from soybean waste is largely Neurospora intermedia, a mould-like filamentous fungus that grows and spreads filaments but does not create mushroom-like components. Collecting Neurospora intermedia strains from diverse sources, he observed that the Neurospora intermedia mould is divided into two types: wild strains found globally and strains adapted especially to human agricultural waste. Oncom only had the second domesticated strain. The researchers propose that food-grade Neurospora intermedia evolved to adapt to human food waste like dogs evolved from foxes to acclimatise to human habitations.

“What we think has happened is that there’s been a domestication as humans started generating waste or by-products, and it created a new niche for Neurospora intermedia. And through that, probably the practice of making oncom emerged,” Hill-Maini said. “And we found that those strains are better at degrading cellulose. So it seems to have a unique trajectory on waste, from trash to treasure.”

Trash to tasty fare

Human indigestible components are a significant contributor to food waste. Humans cannot digest cellulose, a crucial component of plants. The researchers discovered that Neurospora intermedia strains can chemically change 30 different types of plant waste, including sugar cane bagasse, tomato pomace, almond hulls, and banana peels. Furthermore, they converted indigestible plant material—polysaccharides derived from the plant cell wall, including pectin and cellulose—into digestible, nutritious, and pleasant food in roughly 36 hours. Furthermore, unlike the natural strain, certain mushrooms, and common moulds, the domesticated Neurospora strain utilised in oncom did not produce any toxic toxins to humans, making it safe for human eating.

“The fungus readily eats those things and in doing so makes this food and also more of itself, which increases the protein content,” Hill-Maini says. “So you actually have a transformation in the nutritional value. You see a change in the flavour profile. Some of the off-flavors that are associated with soybeans disappear. And finally, some beneficial metabolites are produced in high amounts.”

Tasty delicacy

“The most important thing, especially for me as a chef, is, ‘Is it tasty?’” says Hill-Maini. Sure, we can grow it on all these different things, but if it doesn’t have sensory appeal, if people don’t perceive it positively outside of a very specific cultural context, then it might be a dead end.”

Vayu Hill-Maini examined the Neurospora strains and found one of them was domesticated to human food waste.

Partnering with Munk at Alchemist, the researchers assessed the palatability of red oncom to European clients who had never had it previously. They discovered that the taste created by the mould was not as polarising and powerful as blue cheese. When the chefs at Alchemist grew the mould on peanuts, cashews, and pine nuts, the flavour was 'milder, savoury type of umami earthiness', and when inculcated on rice husks or apple pomace, it offered 'fruity notes', delighting the test clients' gastronomical palates.

A new way of cooking and looking at food

This resulted in the Alchemist's fusion innovation, Neurospora dessert, intermedia: a bed of jellied plum wine topped with unsweetened rice custard inoculated with Neurospora, fermented for 60 hours and served cold, topped with a drop of lime syrup made from roasted leftover lime peel. The enzymes from domesticated Neurospora caused the mixture to emit sweet, fruity flavours, dramatically changing the aromas and flavours. "It was mind-blowing to discover aromas like banana and pickled fruit without adding anything but the fungi itself. We first thought of developing a savoury meal, but the outcomes prompted us decide to offer it as a dessert," adds Munk.

The researchers' findings were published in two key papers: Neurospora Intermedia from a Traditional Fermented Food Enables waste-to-food Conversion, published in Nature Microbiology, and From Lab to Table: Expanding Gastronomic Possibilities with Fermentation using the Edible fungus Neurospora Intermedia, published in International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science.

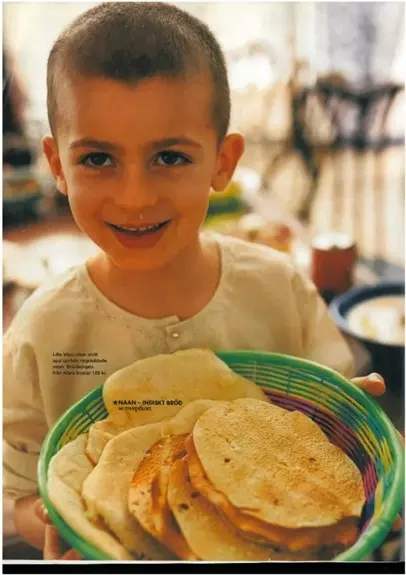

Vayu Hill-Maini as a child at Kitchen; he had developed interest in cooking and science early in his childhood.

Inspired by the outcomes of combining science and culinary abilities, the Alchemist recently opened Spora, a food innovation centre that focuses on upcycling food waste into edible, tasty meals. "The science that I do — it's a new way of cooking, a new way of looking at food that hopefully makes it into solutions that could be relevant for the world," Hill-Maini says.