- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Ghibli trend has become the unwitting tool for propaganda in New India

Hours after the terrorist attack in Kashmir’s Pahalgam on April 22, the photograph of a woman seated beside her husband’s lifeless body went viral, evoking emotional responses from scores of people cutting across religious lines on social media. In no time, the BJP’s Chhattisgarh handle had uploaded a reimagined version of the photograph — rendered in the soft-focus, hand-drawn...

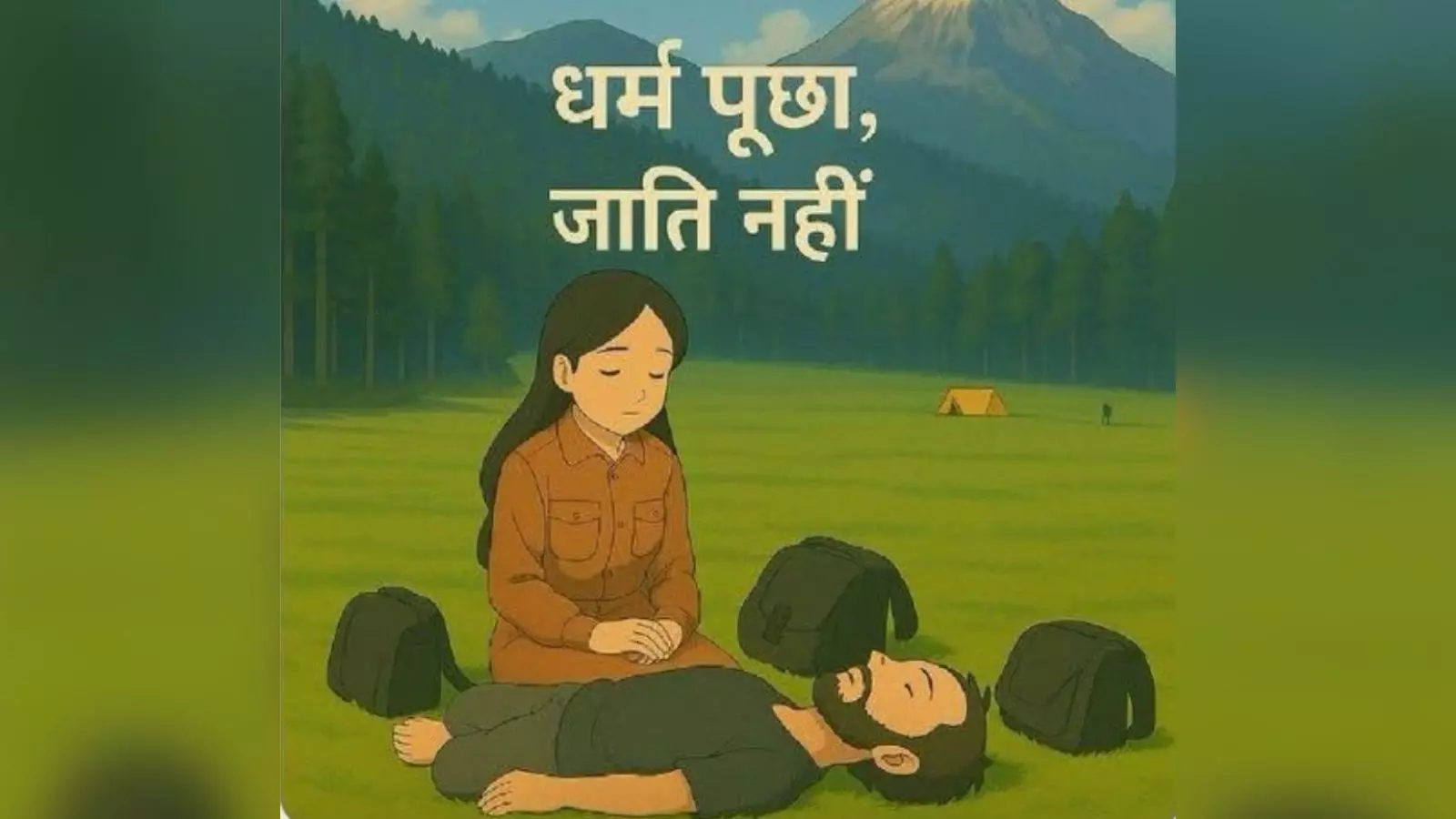

Hours after the terrorist attack in Kashmir’s Pahalgam on April 22, the photograph of a woman seated beside her husband’s lifeless body went viral, evoking emotional responses from scores of people cutting across religious lines on social media. In no time, the BJP’s Chhattisgarh handle had uploaded a reimagined version of the photograph — rendered in the soft-focus, hand-drawn style associated with Studio Ghibli, the Japanese animation house known for its romanticised representation of everyday life — appended with a caption in Hindi written on top, “Dharm phoocha, jaati nahin (They asked religion, not caste)”.

The ghiblified image of the newly-wed woman during the tragedy in which 26 people lost their lives, drew flak from the Opposition as well as social media users, who called out this ‘ghiblification’ of the photograph a “deep insult to victims”. “Making a Ghibli-style AI edit of a terrorist massacre is just sickening. The loss of innocent lives is not aesthetic content. Have a shred of conscience,” a Netizen wrote. What was jarring wasn’t just the tastelessness of it — the way personal grief was repurposed without consent or context — but the sheer speed at which the visual was manipulated and broadcast.

The ghiblified image of the newly-wed woman during the tragedy in which 26 people lost their lives, drew flak from the Opposition as well as social media users, who called out this ‘ghiblification’ of the photograph a 'deep insult to victims'.

What was supposed to be a moment of mourning and grief had become a stylised image in service of affective propaganda to spread animosity between communities. Earlier this month, when violence broke out in West Bengal’s Murshidabad, following protests against the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, ghiblified versions of controversial far-right figures — such as Hindu Samhati founder Tapan Ghosh — were framed in scenes of animated grandeur at rallies. In one AI-made collage, a Ghosh lookalike stands in a crowd, exhorting: “Who is ready to be Gopal Mukherjee (the man who is believed to have led the Hindu resistance of 1946 in Kolkata) to protect their religion?” In other, you can see hordes of men with swords and saffron flags.

In early April, when violence broke out in West Bengal’s Murshidabad, following protests against the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, ghiblified versions of controversial far-right figures were framed in scenes of animated grandeur at rallies.

Ever since ChatGPT’s Ghibli filter, which allows users to generate images in the style of Studio Ghibli, was launched on March 25, these stylised images have taken over our timelines: ordinary people transformed into protagonists of a dreamy world. But virality has a way of diluting meaning. What began as a collective act of escapism soon became a tool of appropriation. Political parties like the BJP were quick to spot the potential of the trend: its emotional pull and — crucially — its capacity to dissolve the hard edges of divisive ideology into the warm, eye-catching hues.

Studio Ghibli (pronounced jib-lee or gee-blee — even fans argue about it) was co-founded by Hayao Miyazaki, one of the greatest animation directors of all time — the Spielberg of animated movies, if you will — in 1985. For years, Ghibli was something that animation fans loved. For a long time, however, it was hard to watch Ghibli films outside of Japan. You had to buy DVDs or find very sketchy online versions. That changed in 2020 when Netflix got the rights to stream Ghibli movies in most countries (except the US). Over in America, HBO Max became the Ghibli home.

Suddenly, everyone had access to over 20 Ghibli films — Spirited Away, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Howl’s Moving Castle, Princess Mononoke, and more. During the pandemic, people stuck at home stumbled upon them and got hooked. Ghibli films are different from what many of us grew up watching. They aren’t loud or fast. They don’t have explosions or superheroes. They take their time. Characters cook, clean, cry, ride trains, stare at the sky. And somehow, it’s magical. It made people feel calm when everything else felt scary. There are no talking animals telling jokes every five seconds. There’s no villain twirling a moustache. Instead, you get strong girls, kind-hearted monsters, and stories where nature matters just as much as people. Spirited Away, Ghibli’s most famous film, is about a girl who wanders into a strange bathhouse for spirits. Sounds weird, right? It is. But it’s also beautiful, smart, funny, and moving. It even won an Oscar in 2003 and beat out Disney’s Lilo & Stitch and Ice Age. That was a big deal.

Now, thanks to ChatGPT, it feels like everyone is into Ghibli. TikTok is full of Ghibli-style filters. Instagram is packed with ghiblified art, food, and fashion photographs. There are Ghibli cafés, Ghibli-inspired travel guides, and even entire college dorm rooms decorated like a scene from My Neighbor Totoro. In late March though, it all began innocuously enough. People started feeding their ordinary, even slightly embarrassing — bad lighting, awkward angles, chipped and flaking walls in the background — photos and getting back pure magic. Using the filter, their grainy passport snap glowed with golden light. And their cluttered bedroom suddenly looked like a neat nook in a storybook cottage. We all marvelled at how the Ghibli filter takes something flat, drab and dreary, and turns it into works of ‘art’, with unmistakable tell-tale touch-ups that make the style so distinctive, so immediately identifiable.

There are Ghibli cafés, Ghibli-inspired travel guides, and even entire college dorm rooms decorated like a scene from My Neighbor Totoro.

But soon, political parties began leveraging the Ghibli aesthetic for promoting its leaders — and propaganda. The Indian government’s MyGov handle released a series of AI-generated images portraying Prime Minister Narendra Modi in various scenarios, such as meetings with global leaders and national events, all rendered in the Ghibli style. Accompanied by captions like ‘Main character? No. He’s the whole storyline,’ these images sought to mythologise political leaders. This appropriation of a distinct artistic style for political messaging has rightfully prompted a debate about the ethical implications of such representations.

The replication of this style through AI not only raises concerns about intellectual property rights but also about the potential dilution of the original art’s intent. Critics argue that using AI to mimic Ghibli’s aesthetic, especially without the studio’s consent, undermines the authenticity and labour inherent in the original creations. Moreover, the deployment of such AI-generated art in political contexts risks commodifying and politicising a style that was never intended for such purposes.

OpenAI, the developer behind the AI tools facilitating this trend, has acknowledged these concerns. In response to the backlash, the company has implemented restrictions on generating images in the style of specific living artists, including those associated with Studio Ghibli. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman admits that AI art isn’t perfect, but says the creative explosion it sparked is worth the trade-off. Speaking on an Indian podcast, he called it a “net win,” even as traditional artists are still figuring out what just hit them and are bracing for impact.

Along with ChatGPT, apps like MidJourney and DALL·E let people turn their selfies into ‘Ghibli-style’ characters or scenes. At first, it looked cool — who wouldn’t want to look like a character from Howl’s Moving Castle? However, over the last month, police advisories and digital safety experts have warned that this trend of AI-generated Ghibli art might look cute, but it opens the door to serious risks. First, your photos could be used to train other AI models, completely without your consent. Your face might end up in future apps, products, or systems, and you’d have no say in it.

Worse still, many of the websites offering “Ghibli-style” art for free are actually shady. Some of them are fronts for phishing scams, which use popular content (like Totoro or Howl) to trick people into giving away personal information. Others sneak viruses or malware onto your device when you download the so-called art. In the worst-case scenario, people can end up losing personal data or money. The police have even warned about fake contests and giveaways using Ghibli branding to lure in users. These scams are clever — and the fact that people trust the nostalgic look of Ghibli makes them even more effective as bait.

Miyazaki, who is not a fan of AI, has called it “disgusting” and “an insult to life itself.” However, the genie of AI — and Ghibli filter — is out and the politics of aestheticised propaganda has already arrived. It now has proof of concept, a test case, and well-oiled machinery behind it. Political strategists have long understood the power of images to shape public sentiment, especially among younger, more digital-native voters. What’s new is the ease with which emotional engineering can now be executed, thanks to AI. The language of the future is visual — and Ghibli, for all its innocence, has become its unwitting syntax.