- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Guwahati's 'slum schools' are keeping the education dream of poor kids alive

It may seem unusual for a 'school' to operate in a small, cramped space without blackboards or benches. However, in a 100-square-foot room with bamboo walls and a rusted tin roof, around 30 children of various ages gather every evening to learn different subjects.This one-room setup is situated among crumbling huts beneath a railway track in Guwahati, Assam. The 'school' in Siloti Basti has...

It may seem unusual for a 'school' to operate in a small, cramped space without blackboards or benches. However, in a 100-square-foot room with bamboo walls and a rusted tin roof, around 30 children of various ages gather every evening to learn different subjects.

This one-room setup is situated among crumbling huts beneath a railway track in Guwahati, Assam. The 'school' in Siloti Basti has been providing education to underprivileged children for over a decade. As its name suggests, Siloti Basti (with "basti" meaning slum in Assamese) is one of many informal settlements scattered throughout Guwahati.

Every evening, Sonmani Jaiswal Das, the 30-year-old educator of Siloti Basti Child Friendly Centre, teaches children of three slums in Guwahati.

“Along with the children from Siloti Basti, students from two neighbouring slums, Lala Basti and Babu Basti, also attend this school,” said Sonmani Jaiswal Das, the 30-year-old educator. Approximately 2,000 families live in these three slums. In addition to Siloti Basti, there are 33 similar learning spaces, known as "Child-Friendly Centres," located in slums or operated from various government-run schools nearby during the evening hours throughout the city.

These centres are strategically situated in different informal settlements across Guwahati, including Mathgharia, Narengi, Bamunimaidan, Bhaskar Nagar, Gandhi Basti, Paltan Bazar, Milanpara, and Gorchuk. They function as mini-schools for underprivileged children. “Run by Snehalaya, a Guwahati-based NGO, these schools support both school-going children and dropouts up to the age of 18 in continuing their education. Financial difficulties, along with a lack of parental support and guidance, are often the main barriers that prevent these children from completing their schooling,” said child rights activist Bijoy Nath.

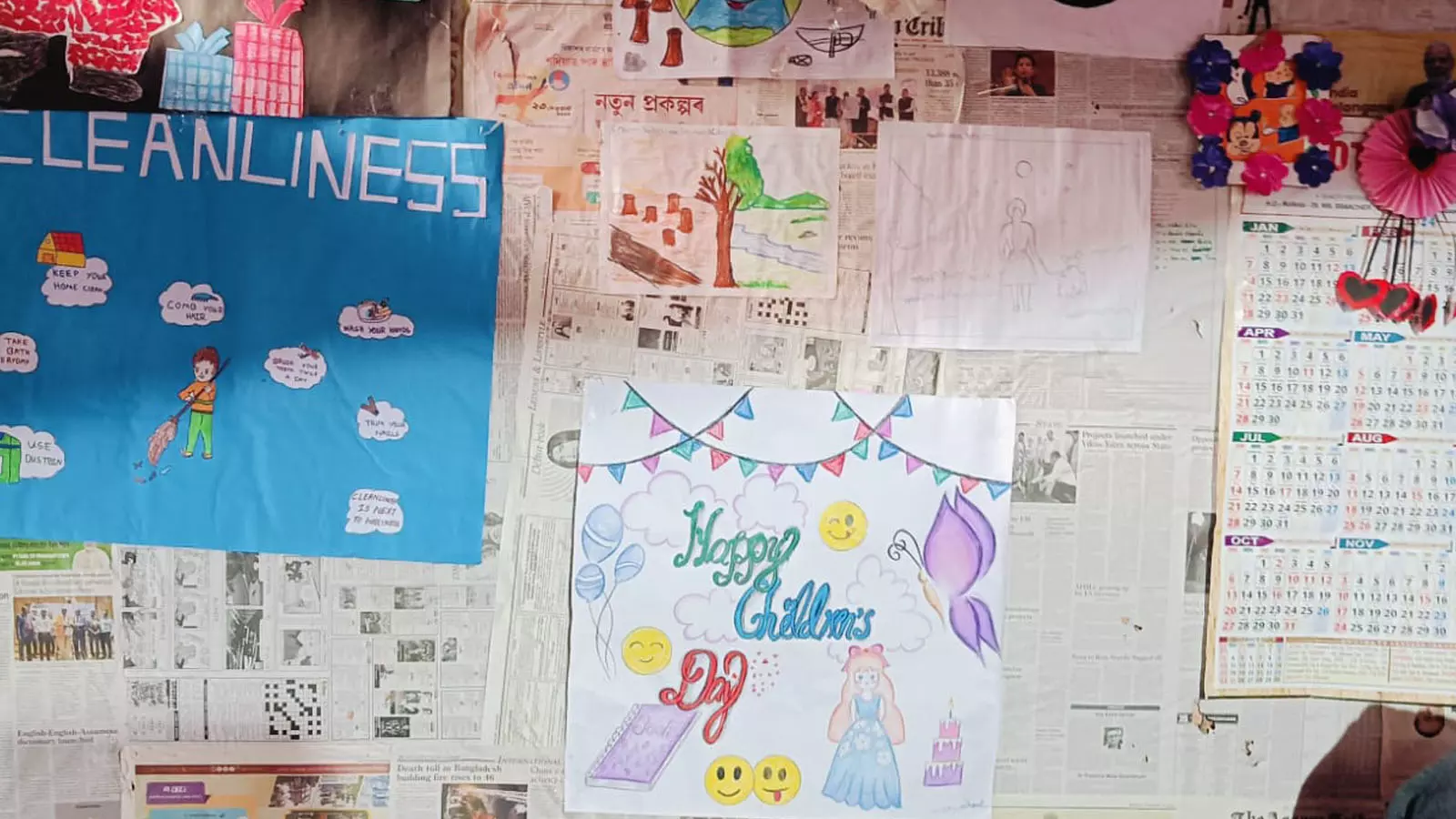

The outside view of Guwahati's Siloti Basti Child Friendly Centre.

Sixteen-year-old Payal Kumari, a 12th-grade student, has been attending classes at the Siloti Basti slum school since 2014. "There is no one at home to help me with my studies. My parents are uneducated. The teachers at the school have supported me with my lessons over the years; otherwise, I might have dropped out like many other poor children," said Kumari, who originally hails from a village in Bihar's Vaishali district.

Kumari aspires to become a lawyer, but she faces several obstacles on her path to completing her education. "My mother is a homemaker, and my father used to run a fruit stall. However, he suffers from severe body aches and can hardly get out of bed. As a result, his small business has been closed for almost three years. My elder brother, who earns a daily wage, is the sole breadwinner for the family," Kumari added.

Her mother, Meera Devi, said that her son earns around Rs 300 to 500 a day. "This is not enough to support a household of five," she added, referring to Kumari's elder sister as well. "We have medical bills to cover for my husband's treatment." Standing outside their bamboo hut, which is on the verge of collapse in Lala Basti, Devi, 45, expressed her family's commitment to supporting Kumari's education despite their financial difficulties.

This one-room Siloti Basti Child Friendly Centre in Guwahati is nestled among crumbling huts beneath a railway track in Guwahati, Assam.

"We want our daughter to finish her education and become a lawyer. We don't want her to become just another dropout. We are grateful that the Siloti Basti school is helping my daughter with her lessons. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to afford any tuition for her, nor could we guide her in her career," Devi added.

Kumari is currently pursuing her twelfth grade in arts at Narangi Anchalik Mahavidyalaya, a government-run institution in Guwahati. She vividly recalls the day the 'slum school' opened its doors more than a decade ago. Kumari and a few of her friends were among the first children enrolled in the evening classes. "Over the years, attending these evening classes has become a daily ritual for me," Kumari said with a smile.

Sonia Kumari, a 17-year-old student at Kanya Magavidyalaya in Geetanagar, Guwahati, said the 'slum school' offered more than just textbook education. "Here, we learn various skills such as painting, singing, dancing, and sports. In addition to learning from our teachers, we (the students) help each other with our lessons. It’s mostly the older students teaching the younger ones. We also come here to discuss and share our life issues, including the financial struggles we face at home," she added.

Sonia, who aspires to be a teacher, lost her parents several years ago. "My elder sister is funding my education, and I am grateful for her sacrifices. Many children from slum backgrounds have an uncertain future. We don’t know how long we can continue our education; many of my friends have had to drop out because their parents can’t support their schooling," she said.

The outside view of Guwahati's Siloti Basti Child Friendly Centre.

The concerns expressed by the teenager are valid. According to the latest Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISED+) report for the 2023-2024 academic year, released by the Department of School Education and Literacy under the Ministry of Education, the statistics for Assam are troubling. The state is classified in the red zone, with a secondary school dropout rate of 19.46%. Bihar has the highest dropout rate in this category at 20.86%.

An official from Assam's education department, who preferred to remain anonymous, acknowledged that the dropout rate in the state was high. "There are many factors contributing to this, including poverty, which prevents children from completing their education. There is an urgent need to establish a strong education system that focuses on providing quality government schools in villages and urban slums for underprivileged children."

The official added that the law of the right to education in India was enshrined in the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (RTE) of 2009. "This Act, along with Article 21-A of the Indian Constitution, guarantees free and compulsory elementary education (classes 1-8) to all children between 6 and 14 years of age. But unfortunately, many children are deprived of education."

Uttam Teron, the founder of Parijat Academy, a school in Pamohi village near Guwahati that provides free education to underprivileged and tribal children, emphasised the need for awareness at the community level to help underprivileged children access benefits under the RTE Act and the Samagra Shiksha Scheme (SSS). The SSS is an integrated government initiative designed to ensure that children receive education from preschool to class 12.

"The discussion surrounding the education of poor children of Assam must be brought to the forefront. Their vulnerability is compounded by their poverty and their belonging to the tribal and Dalit communities, particularly those from the Harijan colonies who work as sanitation workers. In the 21st century, there should be no excuse for failing to educate the younger generation," added Teron.

Father Lukose, founder of Snehalaya, told The Federal that his organisation's motto was to help children in need, particularly orphaned, vagrant, or those in need of protection. "The idea behind starting Child Friendly Centres in different areas of Guwahati is to provide a helping hand to children in finishing their school education."

Sonia Kumari (left) poses with her sister Manisha Kumari (right) near the railway track.

Child rights activist Nath, in charge of the Child Friendly Centre, added that the educator of each centre spent her morning and afternoon time visiting the homes of underprivileged children. "The home visits are to make sure that children living in slums don't miss their schools. The educators also visit neighbourhood schools to see if these children attend their classes regularly. Those who drop out of school are encouraged to attend evening classes in our centres. Thus, these centres act as a bridge school."

Educator of the Siloti Basti centre, Jaiswal Das, said every day was a great learning experience for her, spending time with the children. "The children are lovely, intelligent and articulate. All they need is a little encouragement. Most of the children in my centre are going to regular schools. This way, the centre has succeeded in curtailing the dropout rate among the slum children."

A woman from Babu Basti complains about the lack of drinking water facilities in her slum. Most slum dwellers store water in big buckets drawn from contaminated wells with a high concentration of iron, fluoride and arsenic.

The informal settlements of the urban poor in Guwahati are yet to be recognised as slums because there is no slum board in Assam to do so. Thus, these city dwellers are a part of “no man’s land”—“unrecognised and neglected by the government machineries and society at large". They are mostly engaged in low-paying and hazardous occupations like manual scavenging, domestic work and construction work, to name a few. They are the most invisible residents of the city, spread out in an estimated 163 non-notified informal settlements(as per the Guwahati Municipal Corporation or GMC).

These informal settlements could be found in hills, railway land, private land and wetlands. Most of the inmates of these places, around 20,000 (according to the 2011 census), have no access to necessities like drinking water, sanitation and electricity.