- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Mughal emperor Aurangzeb became India’s favourite ghost

Nagpur, March 2025. Stones rained from the sky, sirens wailed, and news tickers flashed red as protests turned violent. At the centre of it all? A grave. Of the long-dead Aurangzeb Alamgir, the sixth Mughal emperor, who died in 1707 AD. He has, apparently, risen again — as a phantom, a scapegoat, a headline. What triggered the flames was the Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s call to...

Nagpur, March 2025. Stones rained from the sky, sirens wailed, and news tickers flashed red as protests turned violent. At the centre of it all? A grave. Of the long-dead Aurangzeb Alamgir, the sixth Mughal emperor, who died in 1707 AD. He has, apparently, risen again — as a phantom, a scapegoat, a headline. What triggered the flames was the Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s call to demolish Aurangzeb’s old tomb at Khuldabad in Maharashtra’s Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district. The catalyst was a rumour, a desecrated religious text, but the fuel was something deeper: a centuries-long unease with the story we tell ourselves about who we are; when the past becomes too inconvenient, it is either burnt or bulldozed.

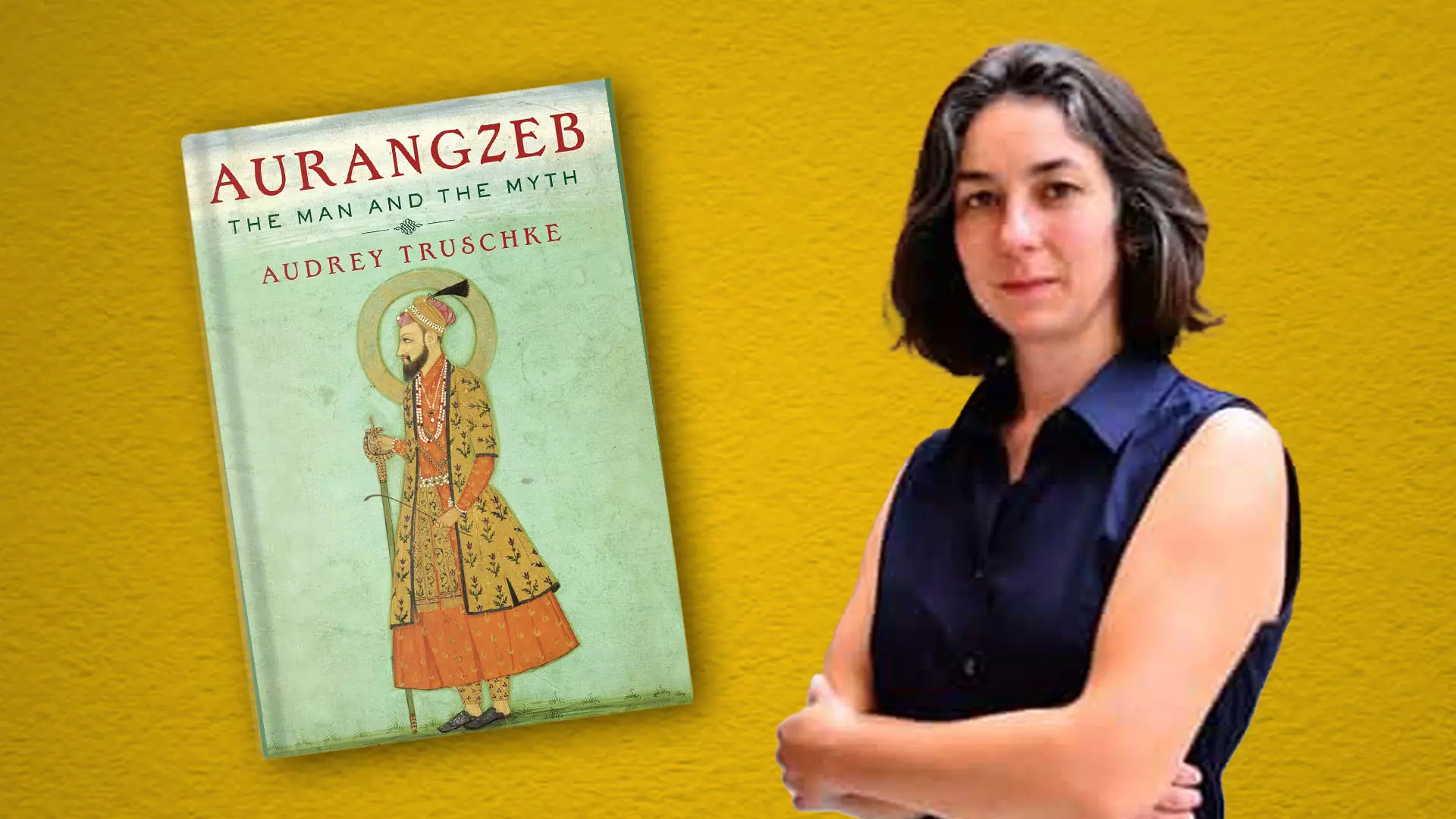

Truth be told, Aurangzeb is no longer an erstwhile Mughal emperor consigned to the catacombs of history; he is an idea linked, somewhat erroneously, to a zealot or a bigot who wantonly destroyed temples. And that idea must be wrestled from the grave each time a modern crisis calls for ancient villains. To twist, weaponise and rewrite history. But who was Aurangzeb? In her sober, unsentimental biography, Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth (2017), Audrey Truschke, a well-known historian of South Asia and a professor at Rutgers University, intervenes. Far from the frothing caricature of Hindu-hater or proto-Taliban, Truschke offers nuance.

In Audrey Truschke's telling, Aurangzeb, who ruled for 49 years over a population of 150 million people, emerges as neither monster nor martyr, but as ruler.

Truschke draws on Persian court histories, farmans, and actual archival records, to sketch a portrait of a ruler both brutal and bureaucratic, devout and pragmatic. He was a puritan, yes, but he also employed thousands of Hindus in his court and donated to Hindu temples.

But nuance doesn’t riot well. You cannot chant it. It doesn’t fit on a placard. Truschke’s work has faced attacks not just because of what it says, but because of what it dares to complicate: that history is not moral fiction. It is not a Marvel universe of villains and saviours.

In her telling, Aurangzeb, who ruled for 49 years over a population of 150 million people, emerges as neither monster nor martyr but as ruler, struggling to hold together an empire fraying from within. “Aurangzeb was a complex emperor whose life was shaped by an assortment of sometimes conflicting desires and motivations, including power, justice, piety, and the burden of Mughal kingship. Such a man would be a challenging historical subject under any circumstances, but especially so given the gulf of cultural knowledge that stands between his time and our own. Aurangzeb is also a live wire of history that sparks fires in the present day. Current popular visions of Aurangzeb are more fiction than reality, however. If we can pierce the haze of myth that shrouds Aurangzeb today, we can begin to recover perhaps the single-most important political figure of seventeenth-century India,” Truschke makes it clear early in the book.

Her earlier book, Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court (2016), disrupted the singular narrative of Mughal intolerance by documenting how Sanskrit flourished in the Islamic courts of the Mughals. The world she reveals is rich in cultural cross-pollination, messier and more beautiful than any nationalist mythology allows. Yet it is precisely that mess which contemporary politics seeks to clean up — not with scholarship, but with stones and brute force. Now, what does it mean to call for the destruction of a grave? A grave is silence. A grave is the end. But the grave of a Muslim, in the times we live in, becomes a target of misguided hate. There is little doubt that in demanding its demolition, VHP protesters are not only trying to erase Aurangzeb’s legacy, they are asserting a claim over what is worthy of memory in the ‘Hindu Rashtra’.

But memory isn’t just what survives. It is also what we choose to repeat. And so, the erasure of a tomb becomes a performance of purification, a declaration that India must be cleansed not just of its Islamic past but of the idea that the past could be plural. In Pakistan, Aurangzeb’s memory undergoes its own contortions. There, he is a hero, pious warrior, and moral icon. Progressives recoil, Sufis and Shiites dissent, but the state-approved narrative lauds his orthodoxy. What unites India and Pakistan, ironically, is not their judgement of Aurangzeb but their mutual impulse to instrumentalise him. He cannot rest in peace centuries after his death.

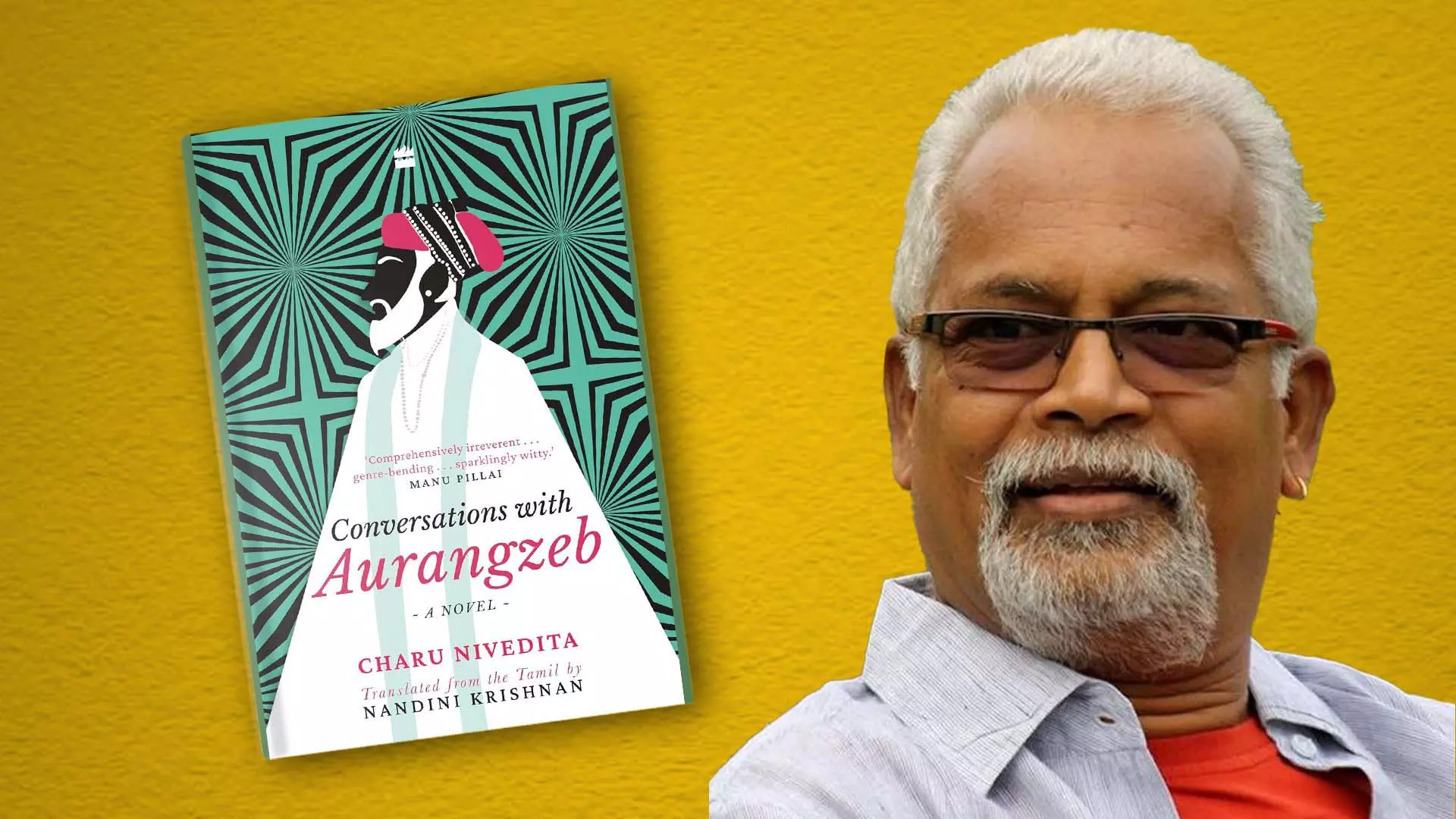

In his irreverent novel, Conversations with Aurangzeb, which was translated into English by Nandini Krishnan in 2023, Chennai-based Tamil writer Charu Nivedita does something astonishing: he gives the Mughal emperor a voice, long after his death. This Aurangzeb, summoned into the body of an Aghori, is not cartoonish. He is pensive, tired, remorseful but not repentant. It is not a defence; it is a dissection. In the novel, satire meets spiritual séance. Jawaharlal Nehru, Sunny Leone and Priyanka Chopra flit across the pages (perhaps to trace the absurd continuity of our mythmaking), as do discussions of Sati, taxes, and genocides. Nehru gets grilled. Rani Mangammal resists Mughal ambitions. Shivaji becomes the emperor’s alter ego. The novel moves like a fever dream, but always in search of the historical itch we pretend not to have: What if we have been wrong?

Chennai-based Tamil writer Charu Nivedita gives Aurangzeb a voice, long after his death.

And in giving Aurangzeb a tongue, Nivedita achieves something that no textbook does: he makes the emperor human. Fallible, frightened, desperate. He also indicts the audience, implicates us in the way we mythologise leaders. Perhaps the most chilling line in the novel belongs to Aurangzeb’s spirit when he says of Ashoka: “Over five hundred beheadings for each dead brother…a hero who went on to embrace and spread the message of peace. History’s heroes are illusory.” That sentence burns like acid on the heroic myth of modern India. Because it doesn’t just say Aurangzeb was flawed. It says everyone is. Aurangzeb becomes the ultimate unreliable narrator of Indian history, implicating both past tyrants and modern ones who wield history as a weapon.

However, Charu Nivedita doesn’t let Aurangzeb off the hook. The novel doesn’t whitewash. What it does is refuse to participate in the national sport of historical ventriloquism. It breaks the genre, lets the dead talk, and in doing so, forces the living to listen without scripts. What we get to experience is not revisionist history, but radical empathy. An insistence that truth is not the opposite of power, but its most difficult companion. This isn’t a novel about Mughal India but about the compulsive need to revise ourselves.

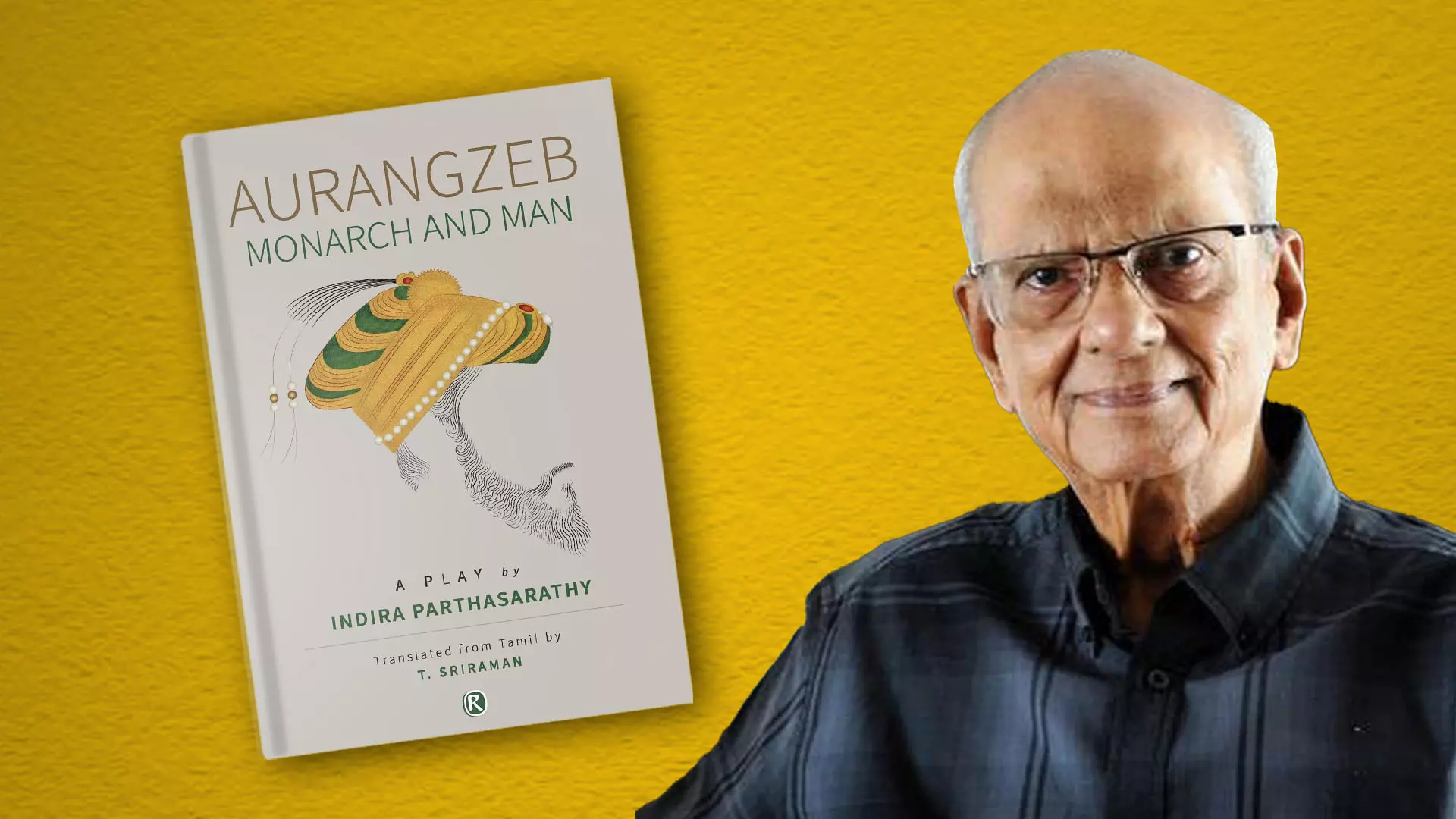

In Indira Parthasarathy’s 1974 Tamil play, Aurangzeb: Monarch and Man, translated by T. Sriraman in 2023, the emperor appears again, not in war rooms or courtroom decrees, but in the hushed loneliness of power. Here is a man who ascended the throne through betrayal and found its golden arms cold. Power, Parthasarathy suggests, devours not just enemies but the self. What connects Truschke’s scholarly rendering, Nivedita’s ghost fiction, and Parthasarathy’s tragic stagecraft is the stubborn humanness of Aurangzeb. None of them excuse his cruelties. But each demands that we also look at his ambition, devotion, paranoia, and regret not as data points but as dilemmas.

In Indira Parthasarathy’s Aurangzeb appears not in war rooms or courtroom decrees, but in the hushed loneliness of power.

The loneliness in the Tamil play echoes something ancient: a king who must rule not just territory but time. Aurangzeb, dead for centuries, still governs our headlines. Who else has such power? When we look at the calls to raze Aurangzeb’s tomb, what are we really seeing? A retributive act? A cleansing? No. It’s the politics of erasure, of remembrance and forgetting. It pretends to delete but actually reproduces the past in an endless loop. It was Babar (remember Babur ki aulad? yesterday. It is Aurangzeb today. It will be some other Muslim ruler tomorrow.

It is no coincidence that this eruption of interest in Aurangzeb coincides with a film, Chhaava, about Sambhaji Maharaj, the Maratha heir. Cinema — especially the films in the last decade or so — and history are locked in a feedback loop: movies reimagine the past, and mobs enforce it. What happens on screen must be enacted in the street. The tomb, silent and centuries old, becomes a prop in a play about vengeance. The ghost becomes real not because of what it did, but because of what we want it to mean now. But to erase Aurangzeb is to erase a part of 17th century Indian history.

To truly understand Aurangzeb, we must first abandon the fantasy that history gives us saints or monsters. It gives us people. People who ruled, failed, hurt, and hoped. The desire to simplify is a failure of imagination. And to simplify Aurangzeb is to lobotomise our past. History is not a database. You cannot just delete a file. You can only refuse to open it. And what you refuse to read, eventually returns — in fiction, in poetry, in stories that live on. This isn’t about one grave. It’s about what kind of country we want to be. A country that faces the past with curiosity or one that flings stones at ghosts. The tomb, after all, is not what haunts us. It is us.

What Truschke, Nivedita and Parthasarthy would perhaps like us to do is to acknowledge that the full Aurangzeb may be our only way to stop resurrecting half of him for violence and anti-minority rhetoric. We must remember that to face Aurangzeb fully is not to vindicate or vilify. It is to confront how easily we abandon truth for the version of the past that aligns with our ideology. And how often, in that certainty, we lose ourselves.