- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How vinyl records are spinning a comeback tale

In many corners of the country’s bustling metros and tucked away in a growing number of living rooms, vinyl records are spinning a comeback tale that’s as rich and textured as the crackle in a well-loved LP. For decades now, these black discs of analogue music had been relegated to dusty shelves, tucked away in corroding trunks, their grooves forgotten in the wake of digital convenience....

In many corners of the country’s bustling metros and tucked away in a growing number of living rooms, vinyl records are spinning a comeback tale that’s as rich and textured as the crackle in a well-loved LP. For decades now, these black discs of analogue music had been relegated to dusty shelves, tucked away in corroding trunks, their grooves forgotten in the wake of digital convenience. But as with many things that feel lost to time, vinyl is returning—loud and proud.

Former bureaucrat A. N. Sharma, a collector of rare records and author of Bajanaama: A Study of Early Indian Gramophone Records and The Wonder That Was the Cylinder, puts this resurgence into perspective. “Did vinyl ever die? Indie pop musicians, especially hip-hop and ska-reggae artistes, had kept faith in this format even through its years of decline. Only now, as I rummage through Haji Ebrahim’s store in Mumbai, Vinyl Street Store in Kolkata or Rhythm House in Chennai, I find a growing number of young people doing the same—from hipsters to eager Gen Z-ers.”

Another gem of Saurav Bhagowati. Photo: Monideepa Choudhury

Sharma, whose hunt for rare vinyl in Indian languages has led him through antique shops, classifieds, and word-of-mouth trails, is spot-on in his observation. According to Vinyl Alliance, the world's leading industry collective for vinyl, sales have seen a slow but steady growth over the last decade and more, with Gen Z as its “driving force”. And while the scale of revival in India is smaller than in Western markets, the vinyl market size did manage to reach USD 62.1 million in 2024 and, according to market research firm, IMARC Group, “is expected to swell to USD 112.5 million by 2033, with its current growth rate of 6.80%”.

The comeback spin

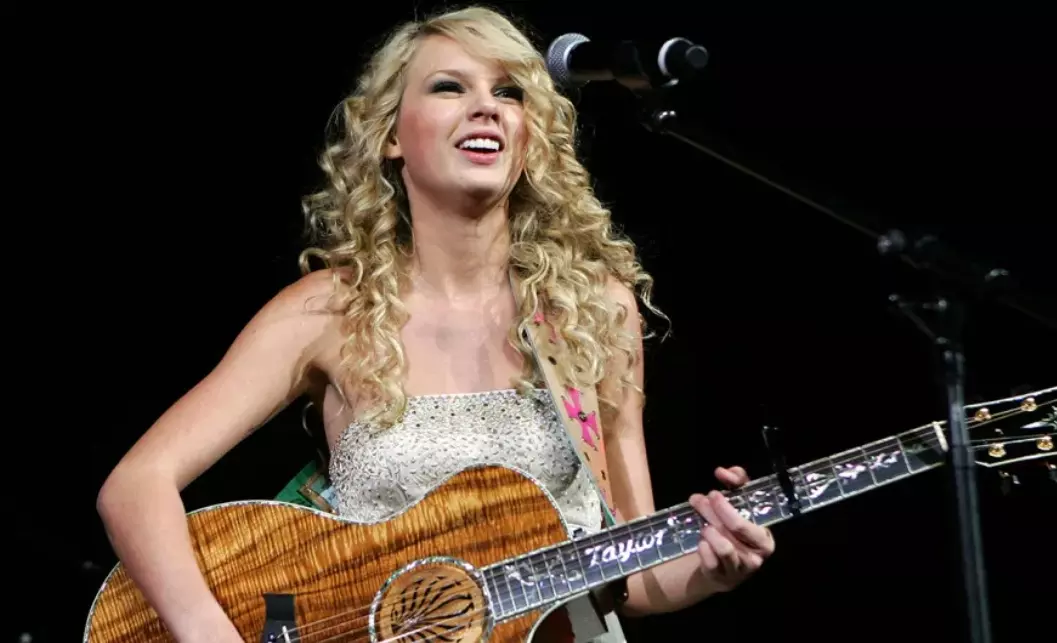

Globally, the return of vinyl began around 2007, not long after the release of Taylor Swift’s titular debut album in 2006, which appeared on vinyl among other formats, and sparked interest among young music lovers, who discovered a retro allure, a tactile connection to a past that seemed freshly “cool”. The momentum swelled in 2014, when Pink Floyd’s The Endless River rippled across the cultural landscape, gaining further weight in 2017, when corporate giant Sony began to press records once more.

Globally, the return of vinyl began around 2007, not long after the release of Taylor Swift’s titular debut album in 2006.

Ashutosh Gotad, copy editor at a Mumbai publishing house, who “randomly” discovered LP at one of the ‘Vinyl Sundays’ of the city’s Port Café, sums the sentiment of digitally-native listeners: “I was done with downloads and streaming. I wanted something rizz, and listening to a record was lit!” Anindita Baruah, Bengaluru-based Human Resource professional and a Millennial, agrees. “Having grown up on compact discs, digital downloads, and now streaming services, listening to vinyl at The Record Room (which is temporarily shifting to another location as of this date) was an emotive experience unlike any other.”

Reels and records

Fuelled by vinyl music charts, Record Store Day—conceived in 2007 to celebrate vinyl culture and record stores worldwide, and most significantly, social media, vinyl sales have surged across continents. In India, stores and labels are highlighting new releases, listening sessions, Record Store Days, and forging connections with fans. Consider, for instance, The Revolver Club in Mumbai—billed as “India's first dedicated record and hi-fi store”—which brings together vinyl enthusiasts through its #escapethealgo campaign. Or Delhi’s Pagal Records, whose Record Store Day is a cherished ritual for lovers of warm grooves and wax-bound nostalgia.

Explains tea entrepreneur, music aficionado, and vinyl collector Saurav Bhagowati, “Social media has helped build a vinyl community—Microgroove is one such—where collectors and enthusiasts share and feel a part of something in an increasingly isolated world. And, as a new generation discovers its magic, it is a nostalgia that Gen X and Baby Boomers are holding up with pride.”

This is largely because vinyl is not just about listening, it is a sensory experience that is “Instagram-able and TikTok-able”. Collectors like Bhagowati and Sharma feel that vinyl’s new place in the sun is “amplified” by the art in the record sleeves, the record-handling, the placing of the stylus on the turntable—all whetting curiosity and building followers. “For the young, music is no longer invisible, no longer in the cloud. You own a piece of it,” smiles Sharma.

India on vinyl

In India, the vinyl revival hums with a distinctly local rhythm. Independent musicians and boutique labels—in genres that range from indie rock, jazz, and experimental music to Bollywood releases, bhajans, ghazals, and folk—are seizing the moment, crafting limited-edition records adorned with bespoke artwork and collectible packaging. Even regional bands have jumped onto the bandwagon. Think Chandrabindoo, Bengal’s influential band, which marked a comeback in December 2024 by releasing its album Talobasha on vinyl. Or ventures like Kolkata’s Free School Street Records, which is shaping the scene with “seminal underground albums on high-quality vinyl”.

In India, independent musicians and boutique labels are seizing the moment.

True, vinyl is still a niche pursuit, but as Gotad says, “it is a growing wave, especially since Bollywood re-releases are getting to be ‘a thing’.” HMV (now Saregama) has a handpicked collection that includes classics like Umrao Jaan, Mughal-e-Azam, and Arth, original recordings by legends such as Kishore Kumar, Lata Mangeshkar, and Asha Bhonsle, and soundtracks from cult favourites like Disco Dancer, Aandhi, Ijazat, and Masoom. “There is also a spiritual album, Bhaja Govindam Vishnu Sahasranam,” says Bhagowati.

Spin stops

India’s love affair with vinyl is a growing constellation of record stops—from Chennai’s Rhythm House to Mumbai’s Music Circle. Rhythm House, with its archive of over 100,000 records, is a labyrinth where Tamil film scores sit beside ‘70s jazz rarities, political speeches, and even old medical recordings. Mumbai’s Revolver Club offers an assortment that ranges from pre-owned to new, Hindi to Western, rock to funk/soul, while also offering turntables and listening sessions for newcomers.

Nearby, sellers like Abdul Razzak and Haji Ebrahim—keepers of second-hand treasures in Hindi, English, Bengali, and Telugu—bridge generations of listeners. Delhi’s gem, Pagal Records Store, also offers everything from punk to classical, reggae to Bollywood. Inventory at Mumbai’s Music Circle is also as varied as it is large, offering choices from Santana to classic ghazals and qawwalis. For Kolkata audiophiles, stopping by the music gully of Free School Street, Symphony & Gramophone Stores at Esplanade, heritage store Melody, Great Indian Records, and more, is pretty much routine.

Online platforms such as Indian Record Co. and On the Jungle Floor (now with a physical store) extend the vinyl experience to even crate-digging. “Record stores are no longer the preserve of aging audiophiles. For music lovers of all ages, there’s something irreplaceable about browsing shelves in person, guided by staff recommendations, and turntable tips,” says Raoul D’Souza, a regular at The Revolver Club. These spaces offer more than music—they are portals of memory and rediscovery. As Bhagowati puts it, “Finding a rare Bollywood pressing or an obscure rock LP is like unearthing a hidden gem.”

Pressed and looking ahead

Today, vinyl is not only being played again—it is being pressed (term for the way vinyl records are made) locally. Besides HMV’s (Saregama) Kolkata plant, music industry veteran Saji Pillai’s Samanvii Digimedia—reportedly India’s first vinyl pressing plant in decades—caters to music lovers with offerings from Bollywood to indie pop. In February 2025, Pillai even released the home-pressed vinyl of the Netflix movie Dhoom Dhaam as the “first-ever record release before a movie premiere”.

Saurav Bhagowati with his collection. Photo: Monideepa Choudhury

Vinyl’s return is real, but it is tempered by cost, with turntables and records, priced ₹2,000 and above, beyond easy reach. And, while Samanvii’s local pressing plant has shortened production time from 6-8 months to under 6 weeks, affordability is still key for growth in a price-sensitive market. So, despite a vast base of music listeners, India’s vinyl publishing revenues are lagging. The revival is real, though still a luxury.