- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How IIWC remains Bangalore’s cultural hub, its window to the world, 80 years on

As Bengaluru sheds its quaint charm for concrete sprawl, the Indian Institute of World Culture, which turns 80 on August 11, remains a sanctuary of intellect, art, and cosmopolitan spirit in the city

It is hard for diehard ‘Old Bangaloreans’ to accept the harsh transformation of their once quaint, charming little city. Just a few old buildings and a smattering of lakes remain to evoke nostalgic memories of old Bangalore. One of the surviving, legacy institutions in the city, which has a long history dating back to World War II, is the Indian Institute of World Culture (IIWC). If...

It is hard for diehard ‘Old Bangaloreans’ to accept the harsh transformation of their once quaint, charming little city. Just a few old buildings and a smattering of lakes remain to evoke nostalgic memories of old Bangalore. One of the surviving, legacy institutions in the city, which has a long history dating back to World War II, is the Indian Institute of World Culture (IIWC). If you stroll down BP Wadia Road from M N Krishna Rao Park, it would be hard to miss the IIWC in Basavanagudi in Bengaluru South.

IIWC, which is listed by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) as a heritage building, is all set to step into the 80th year of its existence. Over the years, its popularity has not dimmed, as visitors continue to flock to this cultural centre, attracted by its huge library, performance hall and an art gallery, all of which are situated amid serene surroundings. So, what is the story behind this cultural centre which dates back to August 11, 1945?

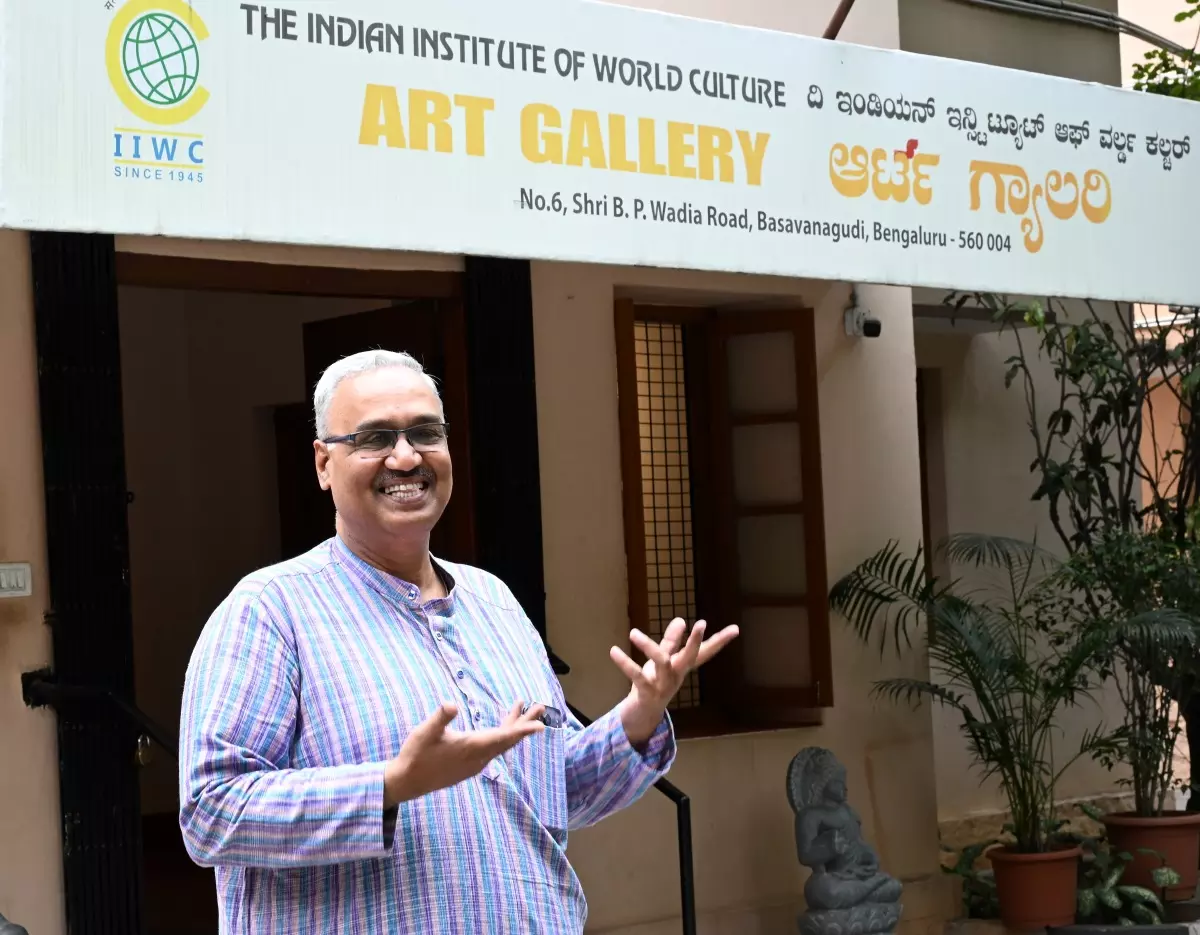

In a conversation with The Federal, Arakali Venkatesh Prasad, IIWC secretary, explains how this centre was born. “When World War II concluded with the surrender of Japan, India heaved a sigh of relief since a large Indian contingent had been out there. Finally, The Charlotte Observer was daily announcing on its front pages: “Peace — it’s over”.

All this “promise of peace” around the world fired up a nationalist leader, theosophist and labour activist, Bahmanji Pestonji Wadia, the eldest son of Pestonji Cursetji Wadia and Mithabai, popularly known as B P Wadia. And, he decided to come up with his own peace initiative in Bangalore.

The Indian Institute of World Culture was founded by theosophist and labour activist Bahmanji Pestonji Wadia, the eldest son of Pestonji Cursetji Wadia and Mithabai, popularly known as B P Wadia.

Belonging to a family of shipbuilders from a village in Surat, a young Wadia had joined the family textile business after the death of his father Pestonji Cursetji Wadia. At that time, he had just completed his matriculation.

In 1904, Wadia sold the flourishing textile venture and became involved with the Theosophical Society founded by Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott. Over the years, he resolved to devote his life to promoting theosophy and even moved to Madras (now Chennai) in 1908, where he managed the Theosophical Publishing House.

Also read: Mysuru Dasara may see Abhimanyu’s last walk as Golden Howdah bearer this year

It was August 11, 1945, when he decided to establish the IIWC, under the United Lodge of Theosophists, a voluntary organisation of students of theosophy with high lofty ideals. In his inaugural speech, Wadia says the institute was conceived “as a cultural centre for ordinary men and women, affording them opportunities to develop those graces of living which are the hallmark of humanism”.

Wadia and his Colombian wife, Sophia Wadia, were truly motivated by a concern for world peace, notes Arakali, adding that they wanted to open the doors of this institute to people hungry for knowledge, and who held high cosmopolitan ideals in esteem. In fact, Wadia made the reasons behind founding IIWC abundantly clear in his Foundation Day address on August 11, 1958, a few days before he passed away.

In his speech, Wadia recalled his words from his first Foundation Day address on August 11, 1945, when peace was declared in a war-torn world. He had pointed out that neither the UN nor the UNESCO had come into existence at that time. But the ideals on which these global institutions stand for today had already influenced the founders to set up the IIWC.

Throwing light on what IIWC stood for, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, popularly known as Rajaji, the last Governor-General of India, in his lecture at IIWC on the Unification of Culture on August 18, 1966, rightly said: “It is an Indian Institute, but aspires to serve World Culture, for it places faith in the value of both diverse special manifestation of culture in various regions and times and the universal element that underlines all cultures. Natural synthesis is inevitable. No artificial uniformity will be adequate to the full possibilities of human culture. What is needed is a frank openness to exchange and mutual understanding”.

B PWadia and his Colombian wife, Sophia Wadia, were truly motivated by a concern for world peace, says Arakali Venkatesh Prasad, IIWC secretary.

Notably, when it was founded, the Institute was named as the Indian Institute of Culture. In 1957, in keeping with its spirit, Wadia registered the Institute as the Indian Institute of World Culture. IIWC is not only a window to the city’s rich cultural past, but also to the first efforts to promote cross-cultural exchange.

While the Institute operated from rented premises for the first four years, Wadia purchased the current place after India became an independent country in 1947 to make the centre more vibrant and introduce more projects and activities. A public lecture hall, along with a public library, was built in 1951, through his own contribution and from donations from philanthropists and the general public.

Also read: How Dharmasthala, Karnataka’s temple town, struggles to shake off its shame

One of the Institute’s earliest initiatives was to establish the William Quan Judge Cosmopolitan Home. In an effort to live up to their noble ideals of universal brotherhood, they started this hostel for students from outside Bangalore. Their motto was to make their members “true citizens of a Republic Brotherhood in this land and brothers to all men and nations throughout the world”.

The Home was named after William Quan Judge, one of the founders of the Theosophical Society in 1875. The students who lived in this hostel belonged to “different nations, religions, castes and communities”. Unfortunately, it was shut down in 1969, after two decades, shares Venkatesh.

Explaining why visitors are drawn to IIWC even today, Ranjini Govind, writer and music and dance critic tells The Federal, “Visitors to the IIWC, which is spread over a total area of 4,000 square feet, find it relaxing to visit the Institute to savour art in a spatial art gallery; listen to lectures and music in the state-of-the-art auditorium and enrich their knowledge in the huge library. IIWC’s proximity to old Bangalore’s shopping localities such as Gandhi Bazar and Chamarajapete, and a number of restaurants make it a favoured destination.”

In her view, in the past Bengalureans felt that if North Bengaluru had the Tata Institute (Indian Institute of Science), South Bengaluru’s pride was the Indian Institute of World Culture. In her diary, Sophiya TenBroeck, one of the members of the IIWC’s executive committee in the early ’60s, recalls some memorable days at the Institute. “We had a bumper crowd when C Rajagopalachari lectured three times (at the IIWC), and when Martin Luther King Jr and his wife addressed us, and also when sitarist Ravishankar performed,” she reminisces.

Writing about Ravishankar’s performance, TenBroeck notes, “Thinking that the audience would leave the auditorium after an hour, I kept vigil on the audience, especially the Germans and Americans. But the hour passed, and there was no sign of people leaving. Ravishankar came to his last piece just before midnight, and he was in so fine spirits and the mood was so elevated that he played the last piece for nearly two hours. He seemed to have the audience in a spell.”

Several Nobel laureates, scholars, scientists, public representatives have lectured at the IIWC and performances by leading singers and dance proponents were arranged every week. Some of the prominent people who have graced the podium at the Institute include governors like General C Rajagopalachari and President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, 19 Nobel laureates including C V Raman J Bhabha; scientist Vikram Sarabhai, erstwhile royals Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar and Travancore Marthanda Varma, American activist Martin Luther King Jr and Tibetan spiritual leader Panchen Lama.

Visitors continue to flock to this cultural centre, attracted by its huge library, performance hall and an art gallery (above), all of which are located amid serene surroundings

The institute is a storehouse of not just intellectual and philosophical endeavours, but also delightful stories and memories. Tenbroeck, who was vice-president, recalls in a souvenir brought out in 1995, “Two German Brothers, who arrived here one morning in a jeep from Afghanistan en route to Colombo, offered to sing at the Institute. We warned the brothers that at such notice, only a small turnout could be expected. The concert began at 8 pm sharp. The operatic voice of the younger Herrkrantz soared out of the hall and reached M N Krishna Rao Park situated just opposite to the hall. Mesmerised park goers, passersby and neighbours (including those acquainted with Western Music) gathered at the gate to listen.”

Talking about the impact of IIWC, nonagenarian and former Chief Justice Venkatachalaiah tells The Federal, “It was clear from its inception that the institute was an academy not only for scholars, but also a platform to promote art and culture with litterateurs, educationists and statesmen sharing their views on the creation of a value system. I have fond memories of my association with this great institute as an outside admirer for seven decades, an integral part of its activities in recent years”.

IIWC, which faced problems during the COVID-19 days, got reactivated after the fear of the pandemic subsided. According to records made available to The Federal, over the years, IIWC has organised over 3,300 lectures, 3,700 music performances, 2,900 dance performances, and screened over 1,150 films.

What’s more, the Institute continues to be a popular choice for well-known publishers to launch books since the library houses a vast collection of books. The IIWC’s library hall, nearly 100 feet in length, is stacked with books running into lakhs on wooden racks.

The IIWC library started off in 1947 with just 4,200 books. Today, the number has increased nearly 50 times and the library is a repository of over a lakh plus books.

“It is worth mentioning that we are one of the largest privately held libraries for free public use in the country. It is a place where students can access reference books at zero cost and a place for social gathering for elderly people,” says Venkatesh.

Also read: Ayyappan Theeyattu, Kerala’s ritualistic theatre form, opens its doors to a female artist

Rukmini Kumar, the librarian-in-charge, points to a leather-bound, six-volume set titled A Survey of Persian Art (1939), as one of the many splendid treasures in this library. You can also find Shakespeare Sonnets, a 1904 volume of Longfellow, Vintage Chambers Encyclopedia of Literature and National Geographic issues from 1916. The library has a collection of 4,000 important works donated by a Yale graduate and philanthropist, the late Dr K T Behanan.

“The library has over one lakh plus books, contributed by generous patrons over the years,” points out Rukmini Kumar. The souvenir brought out in 1995 also talks of a time when the bookshelves rattled one afternoon due to a cave-in at the Kolar Gold Fields over 53 km away. Nevertheless, the library continues to retain its age-old furniture and tradition. Its shelves are a treasure trove for scholars, struggling students, and eager children.

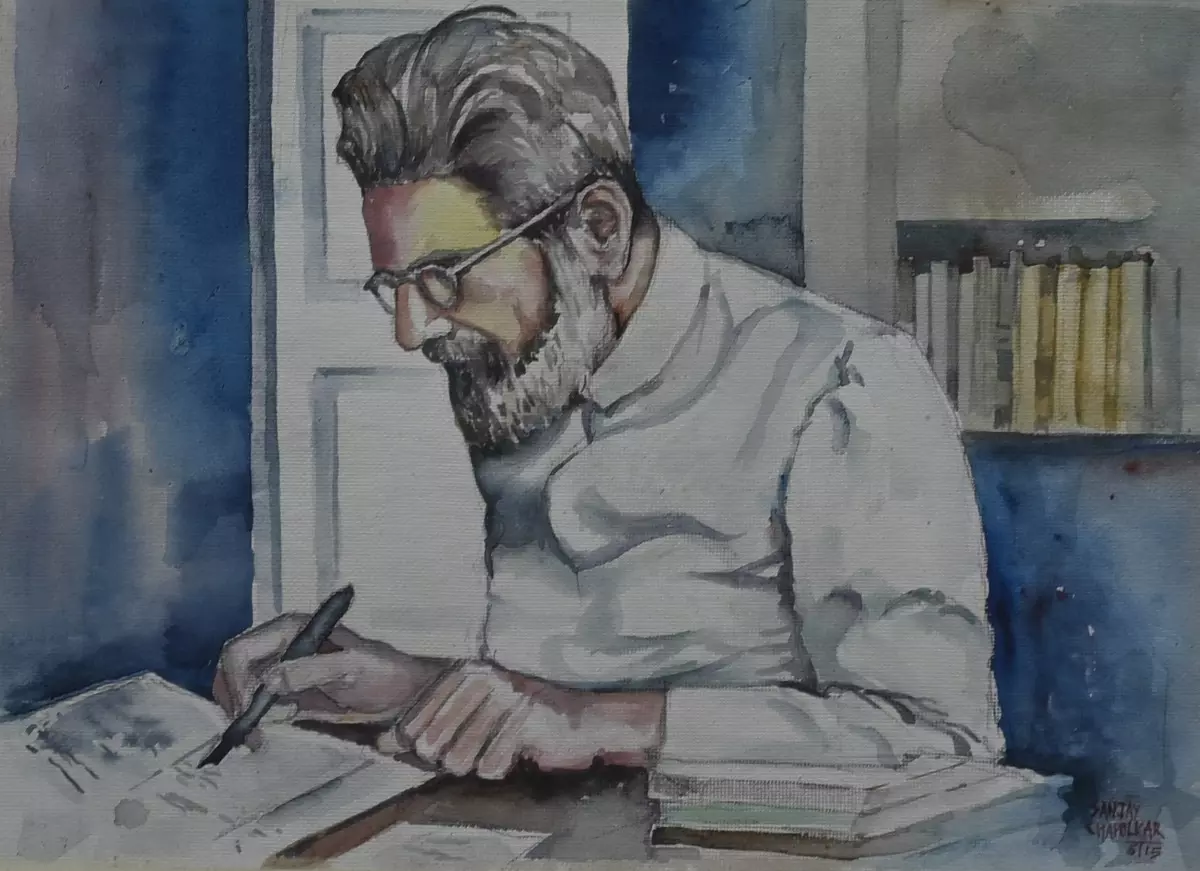

Art gallery at the Indian Institute of World Culture.

An art gallery has also been added at the IIWC. Of late, it has become an attractive hub of art activities. Many noted artists like S G Vasudev have been displaying their works in this space which has a great ambience due to its red oxide flooring and timber rafters on its high ceilings.

In the future, how is the Institute management planning to keep Wadia’s 80-year-old dream alive? Venkatesh says, “The Institute has planned for a renovated campus with two big auditoriums and a multi-utilitarian space, while retaining the library to preserve the reading habit. These ideas will equip us for the next 80 years and help future generations enjoy and safeguard values nurtured so far.”

For musicologist, performer and Sanskrit scholar, T S Satyavathi, IIWC president, the lecture series and performing arts flow simultaneously like a serene river at the IIWC, with nearly 300-plus programmes rolled out each year. “We are partnering with the National Film Development Corporation, Suchitra Film Society and Bangalore Film Society to screen films from across the globe,” she points out.

It is just not these societies. The IIWC collaborates with organisations such as Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (IGNCA), Bengaluru International Centre, Mythic Society, Lalit Kala Academy and Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) to host exhibitions on photography, painting and sculpture.

Also read: How India’s Sacred Groves are protecting biodiversity in a time of ecological crisis

“Going forward, we plan to curate more art forms from Indian and global streams, making them relevant to the contemporary cultural milieu. Any Institution disseminating culture should not be an existential angst; we plan to be pertinent to the times in culture, arts, music and literature,” affirms Satyavathi.

Recalling her association with the IIWC, Satyavathi says, “While I had done a few music performances and given lectures on literature at the Institute, I became part of the executive committee five years ago. It is heartening to read, hear and see the common thread which has held so many people together with a common purpose of promoting world art, culture, heritage, and literature, to make a better world. I am convinced that the next 80 years will surely make the previous generations who contributed towards the Institute proud.”

To mark its 80th year, the IIWC has planned a unique programme titled Eighty-80X10. A film festival, theatre plays, lectures, music and dance performances, exhibitions, and publications are being planned for the occasion. There will be outreach programmes as well. “We have several plans to improve and increase the depth of our activities to nurture a truly cosmopolitan outlook among the public at large,” Satyavathi discloses.

For 85-year-old Dr Ramamani, a former scientist at the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), the IIWC has helped him develop a “better representation” of himself. Visiting the IIWC twice a week for the past 65 years, the institute has become more than a home for him. It is a small island of peace, a hallmark of humanism, in the chaos and mayhem that is Bengaluru city.