- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Karnataka SC quota: Why nomadic communities feel let down by Siddaramaiah govt

Karnataka’s new quota roster providing internal reservation for SC sub-castes has left ‘backward’ nomadic communities unhappy; clubbing them with powerful SC groups has offset benefits, claim their leaders

Could a humble bag made of old cloth subject a woman to risks of sexual assault? There really could be no logical link between the two, could there? But for members of Karnataka’s Beda-Budaga Jangama community, a nomadic group identified as Scheduled Caste (SC) in the state, alleged rape and murder of their women while they were out begging — “carrying such bags” — logic perhaps...

Could a humble bag made of old cloth subject a woman to risks of sexual assault? There really could be no logical link between the two, could there? But for members of Karnataka’s Beda-Budaga Jangama community, a nomadic group identified as Scheduled Caste (SC) in the state, alleged rape and murder of their women while they were out begging — “carrying such bags” — logic perhaps has lost out to sheer anguish.

“If a girl from our community carries a cloth sling bag on her shoulder, she is raped [alleging perhaps that women were assaulted on whim, or that the community was stigmatised and oppressed]. If we go begging or hunting, we get arrested. People look at ragpickers with disgust [in case members of the community take up ragpicking for money]. Many from the community have no roof over their heads and live in makeshift huts. Where should we go? Was it a mistake to be born on this land?” Sanna Marappa’s impassioned outburst carried the weight of helplessness felt by a community that has traditionally eked out a living performing street acts across villages and through fishing and hunting of small animals.

Marappa, the state president of the Welfare Association of the Beda-Budaga Jangama communities, added: “If the state government has provided for internal reservations based on population, then don’t the people of our community count? Have we, who have been backward for generations, no right to be a part of the mainstream?”

Also read: International Literacy Day: How bookstores are helping build communities of readers

Marappa’s distress is echoed by Vireesh K. Vibhuti, state coordinator of the Struggle Committee for Internal Reservation of 59 Untouchable Nomadic Communities. “Clubbing extremely backward nomadic tribes [like Budaga Jangam̧a, Dakkaliga, Sudugadu Sidda, Domb̧̧̧̧a, Shillekyata] together with [the touchable and more advanced] Lambani, Bhovi, Koracha, and Korama caste groups has defeated our 35-year-long struggle [for upliftment],” he alleged.

Vibhuti added: “Even today, nomadic tribes have no educational, economic, or political representation. Does the government want to continue to see us as beggars? Don’t we too have the right to live like everyone else?”

Karnataka’s nomadic communities have been on a protest since last month for internal reservation — the creation of sub-categories within a group that already enjoys a certain quota, to ensure a more equitable distribution of benefits.

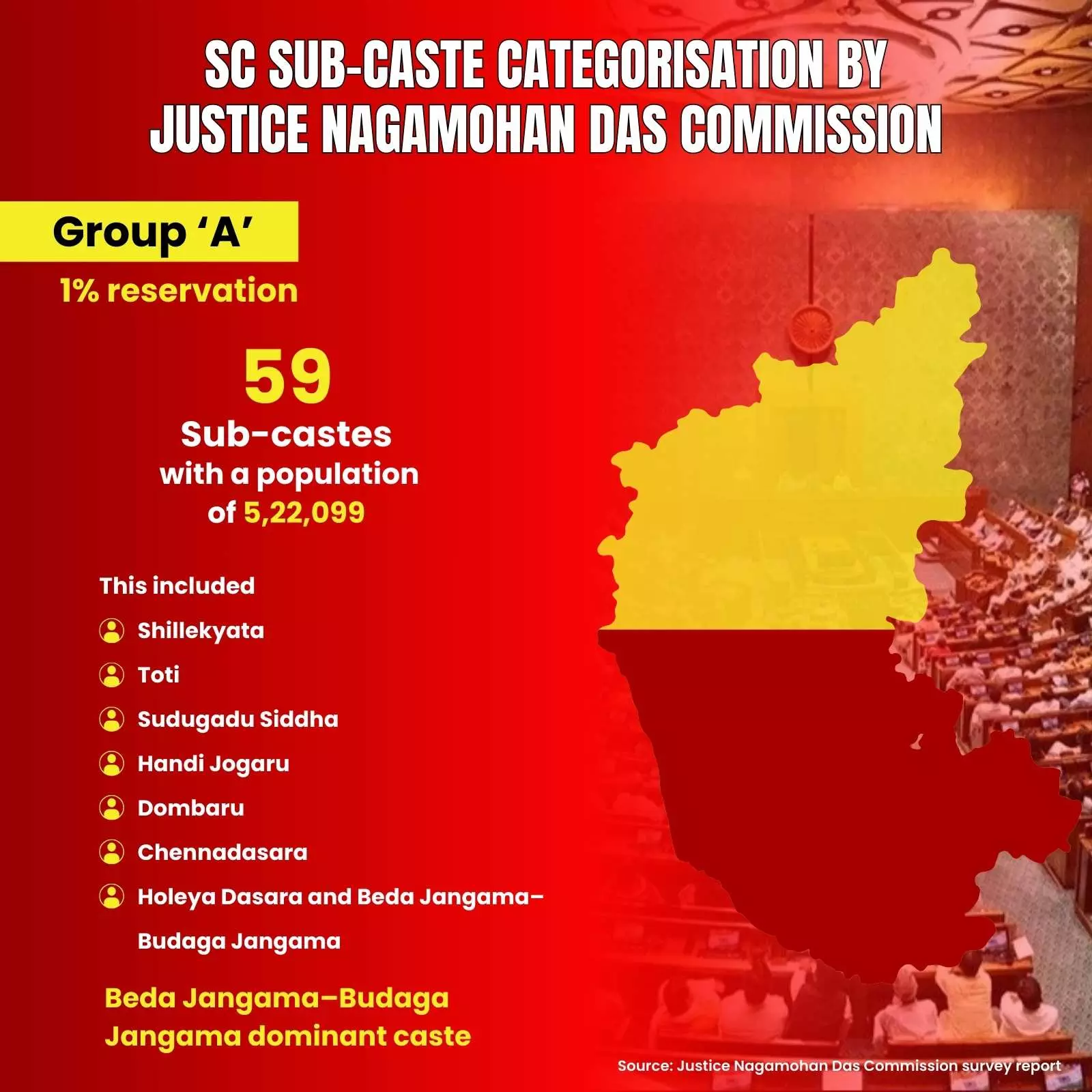

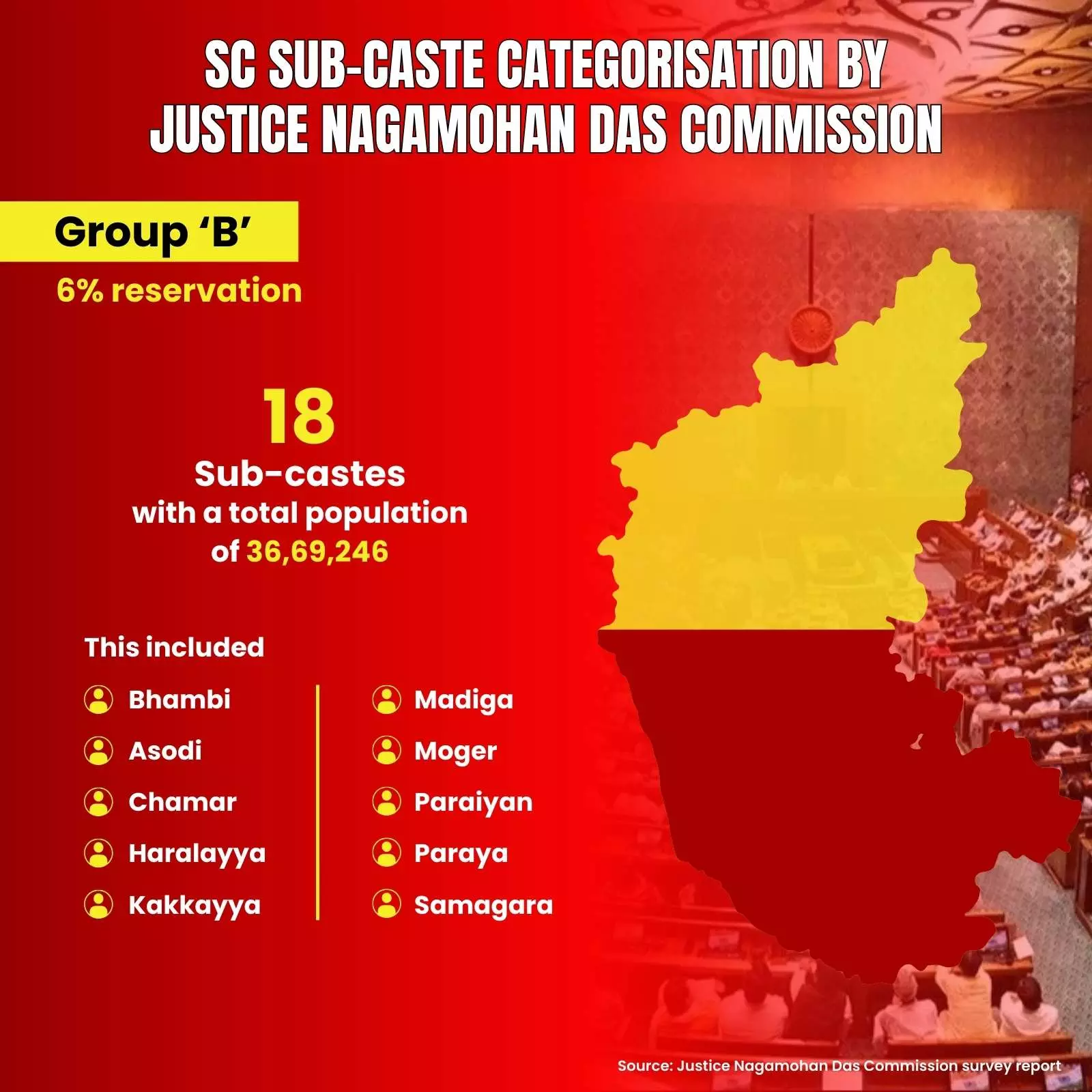

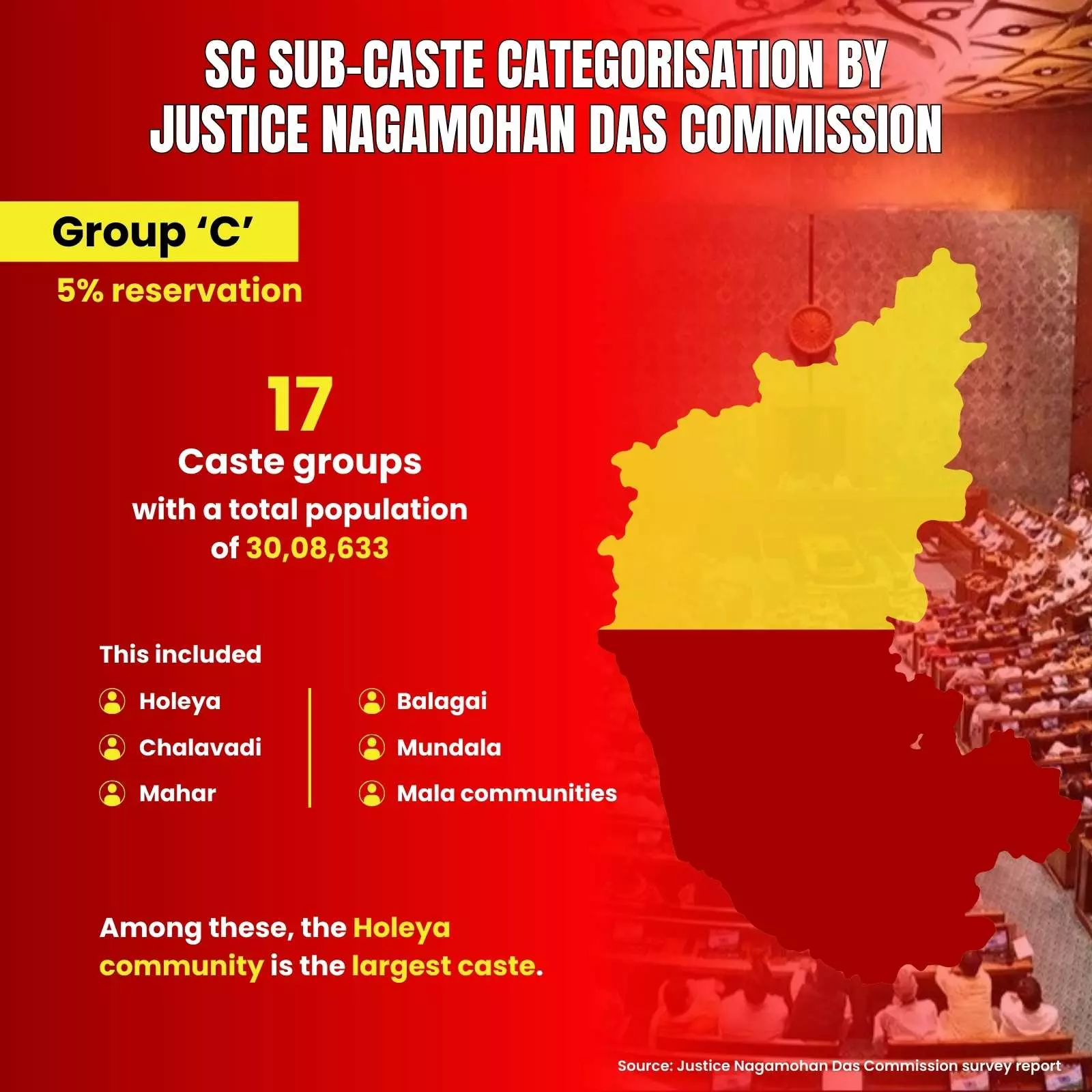

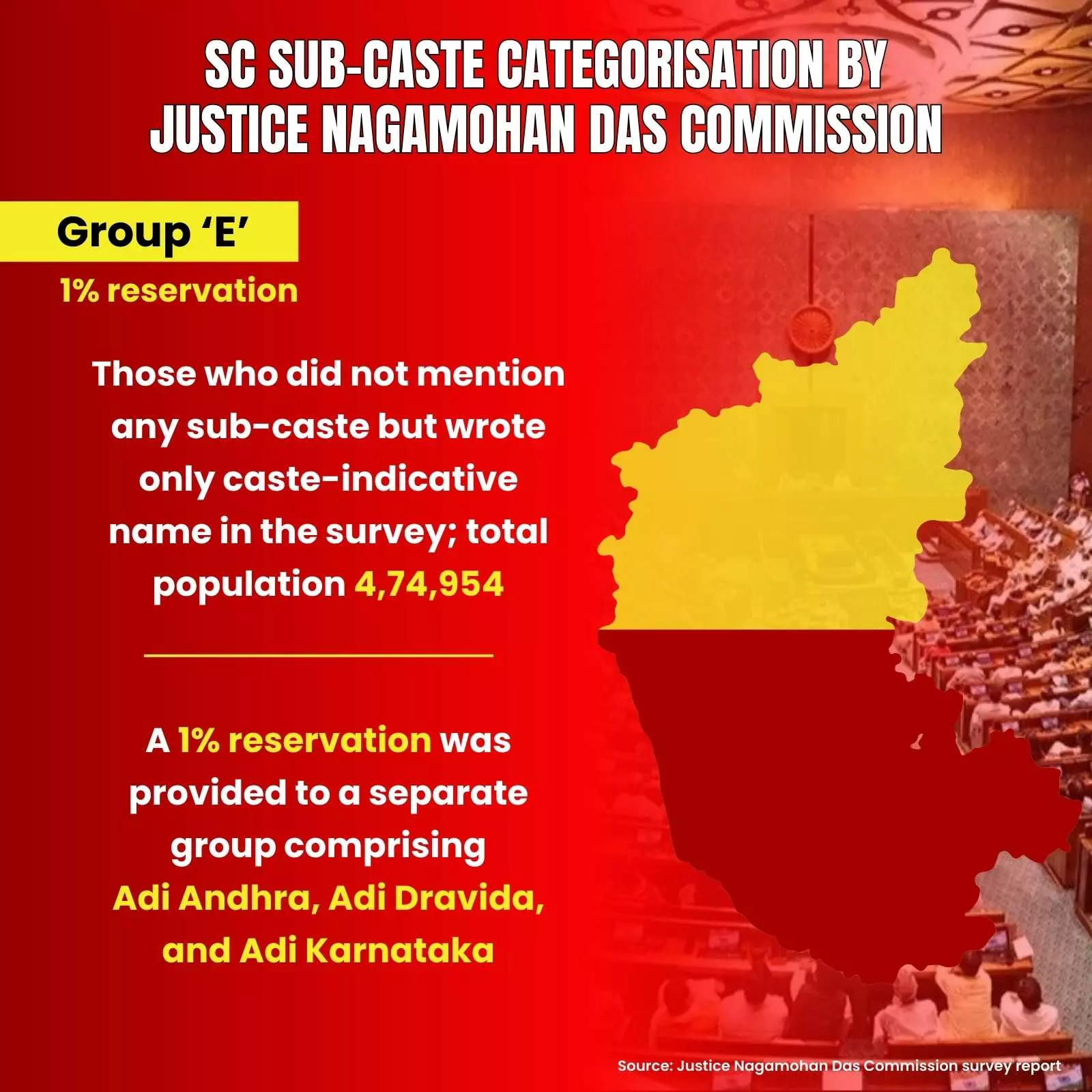

In August 2024, a Supreme Court bench in its verdict on internal reservation had directed that reservation among SC sub-castes should be allocated based on relative backwardness. In May this year, a single-member commission of retired judge, Justice Nagamohan Das, embarked on a comprehensive survey to “help in scientific classification of SCs in Karnataka”. Months later, on September 3, the Siddaramaiah-led Karnataka government announced a revised reservation roster, which while retaining 56 per cent quota for SC, Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Classes (OBC) in the state — 17 per cent for SC, 7 per cent for ST and 32 per cent for OBC —made provisions for internal reservations for sub-castes within the SC quota.

The state government, while announcing the new roster, had stated that the classification was aimed at ensuring a more equitable distribution of educational and employment benefits among all SC sub-castes. Those from the marginalised communities, especially the extremely backward and nomadic groups, however, claimed the grouping by the Siddaramaiah-led government had been done in a way that benefited dominant SC sub-castes at the cost of the more backward ones.

File photo of people from a nomadic community in a village in Karnataka.

While the Nagamohan Das Commission report, submitted to the government in August and accessed by The Federal, had divided SC communities in Karnataka into five categories (based on population), the state government in its new roster reduced this to three. Group A (SC Left/Madigas) and Group B (SC Right/Holeya) received 6% reservation each in jobs and education, while Group C (touchables and nomadic groups) was given 5% reservation. Traditionally, SC Left were sub-castes which were more backward than the SC Right.

“By clubbing nomadic communities with the more influential [sub]castes classified as ‘touchable’, the very purpose of internal reservation has been defeated. Until now, reservations had been allocated based on representation, not population. This [the new] approach has left Adivasis, tribal communities, and nomadic groups ignored and excluded,” claimed Dr. C.S. Dwarakanath, former chairman of the Karnataka State Commission for Backward Classes, in a statement to The Federal.

Also read: How ‘unfair pricing’ of leaves is brewing a storm in Assam’s small tea gardens

Despite clear data from the Justice Nagamohan Das Commission and court directives (a reference to the 2024 SC verdict on internal reservation) the government has not acted on these recommendations, Dwarakanath alleged.

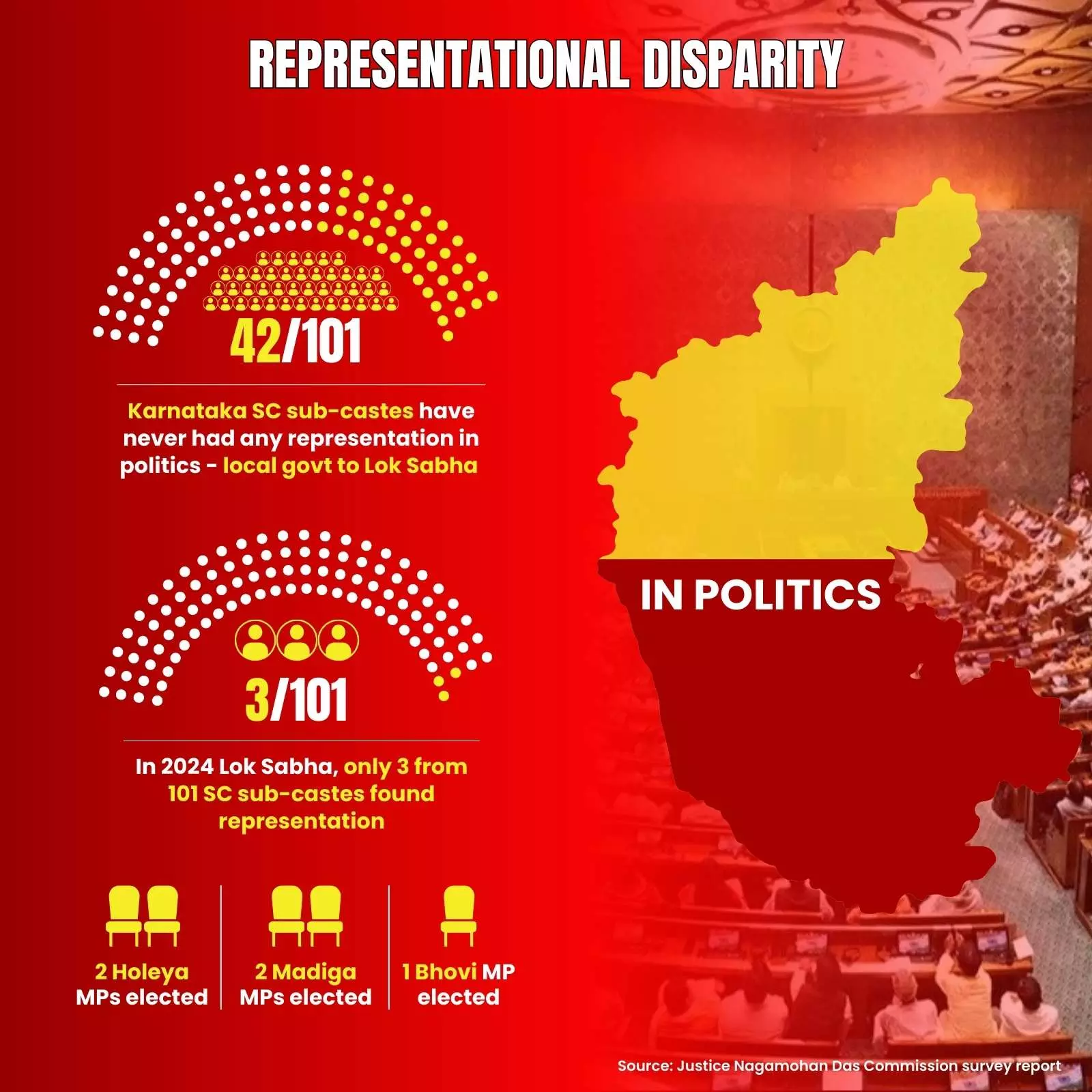

The Justice Nagamohan Das commission report had highlighted deep social, economic, and political inequalities among the 101 sub-castes included under the SC category in the state. Even after 78 years of independence, more than 90 of these sub-castes were found to be still deprived of adequate political representation. Forty-two SC communities had never had any political representation. The reasons, the report claimed, were poverty, illiteracy, small population (of the sub-castes), lack of awareness about the Constitution and democracy, no understanding of political and social democracy, and weak organisation. From the Lok Sabha to the Gram Panchayat, six Karnataka SC sub-castes —among them Holeya, Madiga, Lambani and Bhovi—were found to have the highest representation.

These, and the Adi Karnataka and Adi Dravida sub-castes which had a stronger presence in local governance bodies, also exhibited the same dominance in land ownership patterns and access to government financial benefits.

Nomadic tribes claim to have been among the most deprived, across generations. “Our community [the Sudugadu Sidda nomadic community] is among the most economically and educationally backward,” claimed Rajappa of Kanuru Gram Panchayat in Chikkamagaluru district. He further alleged: “Politics today runs on money. But for us — many in the community still survive on begging — no political party gives us a chance. Even if we gather the courage to contest elections, dominant SC sub-castes won’t let us rise.” Rajappa, who is in a better financial state now and is a local political leader, had contested the Gram Panchayat election in 2020 but lost.

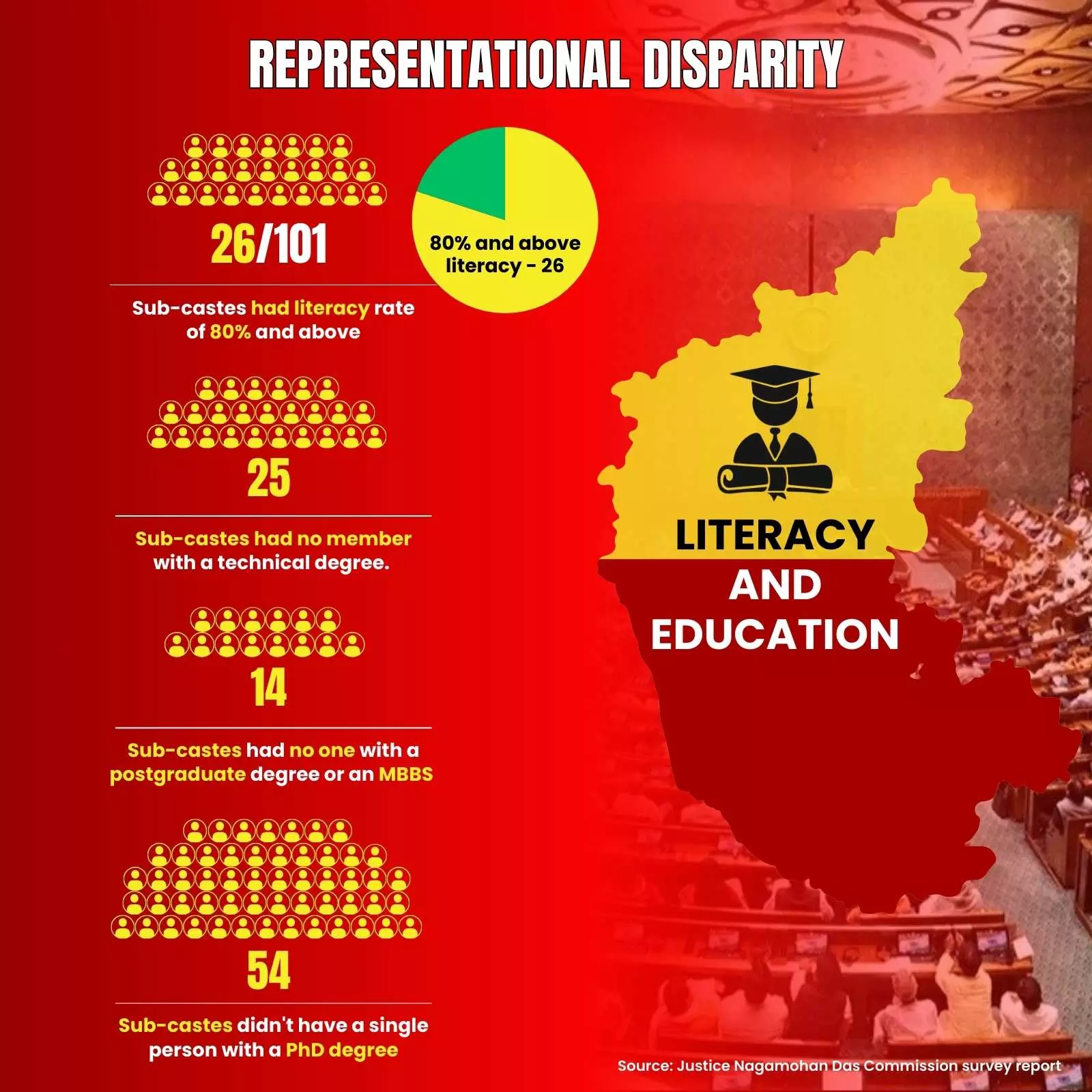

While the Nagamohan Das Commission report highlighted stark educational disparity among the sub-castes included under the SC category in Karnataka — only 26 of 101 sub-castes had a literacy rate of more than 80 per cent — nomadic communities were found to have received less education compared to sub-castes such as Lambani, Bhovi, Madiga, and Holeya. When it came to employment, the report stated only 1.52 per cent of those from SC communities were in government jobs — for the most backward Nomadic and Other (Category A of the report) castes, the share was only 0.81 per cent.

“We had hoped that even a two per cent internal reservation could help us progress. But instead of uplifting us, placing us in the same category as the more advanced Bhovi and Lambani communities will push us further back. Our community [Shillekeyata] has no political representation because of this neglect. If we had proper reservations, we would have also had better access to education and other facilities, leading to [better political] representation. Now even that dream is shattered,” alleged Raju Doddamani, state vice president of the Tribal Mahasabha.

Also read: How West Bengal is pushing back against BJP’s Bangladeshi infiltration narrative

In 2016-17, the state government had prepared a list of the SC and tribal nomadic communities in the state to design development programmes for the nomadic groups. “The Justice Nagamohan Das Commission had studied the lives and conditions of these nomadic groups and recommended reservations for them. However, the state government allotted these reservations to ‘touchable’ castes and pushed us with the ‘powerful’ caste groups. Now, a struggle for preserving our community identity is essential. Until we are given both political and educational representation, we will continue our movement [for internal reservation],” insisted Manjunath B.H., state president of the Shillekyata community.

He alleged: “We believed that Chief Minister Siddaramaiah would uplift the oppressed communities. Instead of helping us, Siddaramaiah has mixed poison into the very food we eat.” Insisting that the Karnataka government must immediately separate nomadic groups from the ‘Category C’ classification and provide them with at least two per cent reservation, ensuring their political and educational representation, Dwarkanath added, “Without these measures, no one has the moral right to speak about social justice”.