- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Worry to wonder: How enumerators mastered use of tech tools for Karnataka’s social and educational survey

A total of 1.7 lakh personnel have been employed to conduct the survey. Enumerators received training from the first week of September in using an Aadhaar KYC app, a facial authentication app, an enumeration data collection system survey app and a geo-location app to record the data.

Working during a festival, when family, neighbours and friends would all be enjoying a holiday, can’t be easy. More so, if the work involves something in which you have no prior experience. Ramesh Menasinakai, a school teacher in Karnataka’s Gadag district, recalls being worried when he found out that as an enumerator for a new social and educational survey that the state was undertaking...

Working during a festival, when family, neighbours and friends would all be enjoying a holiday, can’t be easy. More so, if the work involves something in which you have no prior experience. Ramesh Menasinakai, a school teacher in Karnataka’s Gadag district, recalls being worried when he found out that as an enumerator for a new social and educational survey that the state was undertaking — which coincided with the Dasara (Dussehra) holidays in Karnataka — he would be using a new app to record the data. He had never used geo-tagging before, one of the new technologies being used in the survey, he told The Federal.

Menasinakai was not the only one to feel such trepidation. Many of the other survey enumerators The Federal spoke to confessed to having been apprehensive when they were initially told about the enumeration data collection system (EDCS) mobile app used for the survey.

On September 22, the Karnataka State Commission for Backward Classes (KSCBC) launched a new social and educational survey, aimed at recording the social, educational, economic, and political conditions of the state’s population. The ongoing survey, commonly referred to as a caste census, is not the first of its kind exercise undertaken in Karnataka. An attempt, made in 2015, led by then KSCBC chairman H. Kantharaju, faced strong opposition from some dominant communities. The government at that time did not accept the report. Later, in 2024, former chairman Jayaprakash Hegde reviewed the 2015 data and submitted a new report. However, it was rejected in 2025, leading to a decision to conduct a completely new and scientific survey. The current commission, led by Madhusudan R. Naik, has been asked to ensure accuracy, transparency, and proper use of modern technologies. According to officials of the commission, the current survey is not just about counting people, but about creating a reliable database for policy, welfare schemes, and development planning. Where it differs from previous such exercises is in the use of apps, which, it is claimed, will allow for real-time monitoring, data security, and accuracy.

“Following the objections raised against the report of the H. Kantharaju Commission in 2015, it was decided to use technology [for this survey]. Four apps are being used in the survey — an Aadhaar KYC app, a facial authentication app, an EDCS survey app, and a geo-location app. Using these four software tools, data is being recorded accurately and quickly,” KSCBS member secretary, K.A. Dayanand, told The Federal in a statement.

Preparations for the survey had begun in August, with enumerators across various districts receiving necessary training from the first week of September. According to KSCBC officials, two rounds of training were completed by September 19. In Greater Bengaluru, where the survey began on October 4, a total of 17,000 personnel were trained.

The training went a long way in removing Menasinakai’s fears. “After a week of training, I could see how quickly we could record each household and check if anyone was missed. It feels like we are doing something bigger than just counting numbers,” he added.

Also read: Karnataka SC quota: Why nomadic communities feel let down by Siddaramaiah govt

Artificial Intelligence (AI) plays a key role in making this survey a technical model. According to Dayanand, data is being collected in two stages. In the primary data collection stage, enumerators gather information directly from households, covering social, educational, and economic details. In the secondary data collection stage, state departments, the Karnataka Public Service Commission (KPSC), and the Karnataka Examinations Authority (KEA) provided information on how many jobs each community has received. AI is used to process and consolidate the data, helping in cross-verifying data, eliminating errors, and preparing a final, accurate report. The use of AI allows the survey to handle millions of households systematically, ensuring speed, accuracy, and transparency, which has never been achieved in previous exercises, said an EDCS surveillance committee member. The combination of AI, geo-tagging, and mobile-based data collection is what makes this survey a technological benchmark for other similar exercises in the future across India, feel some.

Survey being conducted at Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge's residence. Photo courtesy Karnataka Backward Classes Commission

The EDCS, developed jointly by experts from the E-Governance Department, the Energy Department, and the Directorate of Electronic Service Delivery, allows enumerators to collect, upload, and verify data in real time. Every household is assigned a Unique Household ID (UHID), linked to its electricity meter revenue registration (RR) number and geo-location. The app ensures that every home is accounted for, no house is counted twice, and data cannot be manipulated. This app is being considered the digital heart of the survey, centralising all information and allowing supervisors to track progress in real time. It also eliminates alleged delays, errors, and inefficiencies of paper-based surveys.

Enumerators use the app to ask 60 questions covering social, economic, and educational parameters, prepared in consultation with technical experts from the World Bank and Indian Institute of Management (IIM), among others. The questions from the earlier H. Kantharaju Commission survey were also considered, said Dayanand. Data is uploaded instantly to a secure government server. A “search” feature in the app allows quick location of households and verification of data, making the process more accurate. Supervisors can monitor enumerator performance and address issues promptly.

For those who prefer not to provide data in person, an online self-declaration option is available. People can scan a QR code, enter Aadhaar or ration card numbers, receive an OTP, and complete the questionnaire online.

The launch was, however, not without its share of teething troubles. The EDCS app faced several technical challenges in the beginning, including server downtime, OTP delays, and sudden crashes. Enumerators sometimes saw “Upload Not Successful” messages, which forced them to reinstall the app, erasing previously entered data.

Also read: ‘Dead’ voters walking in Bihar, hundreds deleted from rolls in villages near Patna

Priya Patil, an enumerator from Davangere, lost some data when the upload failed and had to redo entries. According to Raghavendra, an enumerator from Chitradurga, OTP verification delays had slowed work initially, especially in remote villages. “But once the server issues were fixed, we could survey thousands of households daily without errors. Technology now feels like our biggest ally,” he said.

While initially, only one to two lakh households could be surveyed daily. After the initial tech issues were fixed, the system now handles 12–16 lakh households per day, said survey supervisors.

Early in the survey, some geo-tagging errors caused confusion. UHID numbers were sometimes not correctly linked to locations, which slowed progress. These issues were resolved by conducting block-by-block surveys to ensure systematic coverage and adding a search feature to quickly locate households, among other measures.

Anil Kumar Shetty, a teacher at a rural school in Udupi, admitted that geo-tagging errors had confused them initially, as some households didn’t appear correctly on the map. “We learned to verify each location block by block. Now, I feel proud that no house is left uncounted,” he added.

“In the initial phase of using the EDCS app, some technical issues were observed — such as delays in receiving OTPs, app hanging, and incorrect geo-location display. Step by step, all these glitches were fixed, and now the app is functioning accurately,” said Dayanand. Supervisors, too, confirmed that all major issues have been resolved, and the system now supports 1.75 lakh enumerators simultaneously under an “open-to-all” access mode.

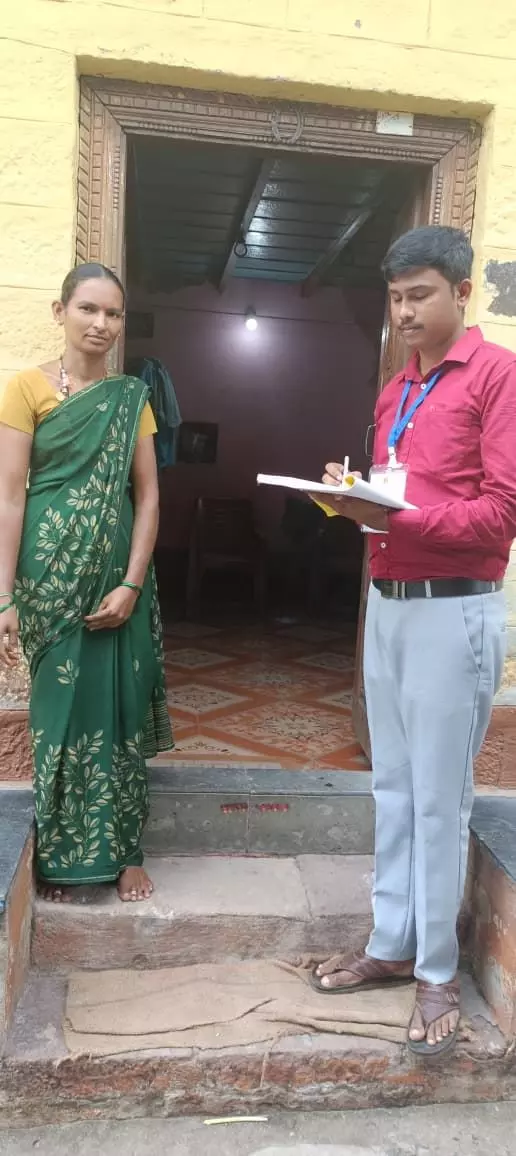

Survey at a house inn Belagavi. Photo courtesy Karnataka Backward Classes Commission

Most enumerators share both pros and cons of using technology for the survey. Photographing each household was a new experience, said Mahesh Gowdar, a teacher from Koppal (many of the enumerators have been part of similar surveys or censuses in the past). “Some families were shy, but once they understood it was for the survey, they cooperated. Technology is helping us build trust as well as accuracy,” said Gowdar. Sushma N., a senior teacher from Mysuru, meanwhile, recalled the survey’s progress being slow during Dasara, as many people were away from home. “But the online self-declaration portal allowed residents to submit data later. That flexibility makes this survey smarter than any I’ve seen before,” she said. The recording of answers to 60 questions per household was exhausting, added Kavita Rao, an enumerator from Dakshina Kannada, but the app helped in the backend to check for errors. “We are collecting huge amounts of data, but the system ensures it is accurate, which was impossible before,” she said.

For Deepak Gowday, teacher at an urban school in Bengaluru, convincing residents to participate was a challenge, as many worked in shifts or lived in rented flats. “But when we explained that the data would help design better welfare schemes, some volunteered online. Technology made that possible,” he said. The tech tools also helped enumerators reach out better to those hesitant to participate. Meera K., a teacher from Raichur, recalled some among the elderly being hesitant to open doors. “Using geo-tags and UHIDs helped us explain that we only needed household info and photos, and no personal documents. Gradually, people started cooperating more,” she added.

The Karnataka caste-census model — combining geo-tagging, AI and mobile data collection — feel some, can serve as a practical blueprint for the Chief Election Commission’s upcoming Special Summary Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls. Geo-coordinates for every household would reduce duplicates and clarify polling-jurisdiction disputes; AI cross-checks against existing databases can flag duplicates, minors, bulk registrations and other anomalies in real time; and a robust mobile app (with offline mode, photo/document upload and built‑in validation) would speed fieldwork while reducing paper errors. Crucially, strong encryption, limited access to sensitive fields and public-awareness drives would address privacy concerns, while transparent dashboards and citizen verification portals would let residents check their details before finalisation — improving accuracy and public trust.

These safeguards take on extra importance after Congress MP Rahul Gandhi’s recent public allegations of “vote theft”, owing to irregularities in the 2024 Lok Sabha election and electoral roll revision in Bihar. The leaders has claimed that electoral rolls were prepared “not in a scientific way”, names were deleted and fake or bulk registrations (including many names at single addresses) were used — accusations the Election Commission has publicly countered while asking for formal evidence. “This method can answer all such allegations,” said a former officer with the Chief Electoral Office (Karnataka) speaking on condition of anonymity, noting that geo-tagging plus AI audit trails would make addition/deletion histories auditable and disputes easier to resolve.

Also read: Eviction drives in Assam’s Golaghat leave migrant Muslim families pushed to a corner

With the survey yet to be completed, chief minister Siddaramaiah extended the deadline from October 7 to October 12. In Greater Bengaluru, it is scheduled to continue till October 24. A total of 1.7 lakh personnel — including school teachers, departmental employees, and Group C staff from corporations — have been employed to conduct the survey, said commission officials. As the survey is being conducted during the Dasara vacation (schools reopen on October 18), the enumerators are being given higher allowances, said sources. Teachers will also receive special leave or leave encashment options. Each block for the survey includes 100–150 houses, and teachers are being paid ₹20,000 per block for completing the survey.

For Priyanka R, a young teacher from Koppal, however, the big takeaway from the survey was not the money, but the first-hand experience that a caste survey could use so much technology. “Seeing our UHID numbers linked to electricity meters and geo-locations felt futuristic. It’s like the ‘Digital India’ dream [an initiative of the BJP-led government at the Centre] is happening right here,” she said.