- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Myanmar’s military crackdown has galvanised a defiant press corps

As press freedom is curbed by the Myanmar junta, a defiant band of media outlets like Mizzima News has turned rebel-held jungles into studios, continuing their work with renewed purpose

A swarm of insects, attracted by lights, hovers around the camera as a group of media workers and journalists transmit their news feed from a makeshift bamboo shelter inside a thick jungle. This was the scene at the headquarters of a leading independent media outlet in Myanmar as several news outlets have moved into rebel-controlled jungle bases to operate beyond the reach of the...

A swarm of insects, attracted by lights, hovers around the camera as a group of media workers and journalists transmit their news feed from a makeshift bamboo shelter inside a thick jungle.

This was the scene at the headquarters of a leading independent media outlet in Myanmar as several news outlets have moved into rebel-controlled jungle bases to operate beyond the reach of the military junta.

Newsrooms were forced to go underground after the junta revoked the publication licenses of 15 media outlets following the February 2021 coup, which overthrew the country’s democratically elected government, led by its ruling party, the National League for Democracy (NLD).

“Due to the severe constraints imposed on independent media by the regime in Naypyidaw, 64 newsrooms have been compelled to operate from exile over the past four years,” stated the Independent Press Council Myanmar (IPCM) on the occasion of World Press Freedom Day (May 3). The IPCM itself was founded in exile, in Thailand, by a collective of displaced journalists in December 2023.

The crackdown has been brutal. More than 200 journalists and media professionals have been detained, and at least seven have lost their lives in the line of duty, according to various media watchdogs.

Myanmar ranks alongside China and Israel as the world’s three worst jailers of journalists, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the New York City-based nonprofit organisation, which has correspondents around the world. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) World Press Freedom Index ranks it 169 out of 180 countries globally.

Yet, rather than silencing dissent, the military’s oppression has galvanised Myanmar’s press corps. Journalists, driven by an unyielding commitment to truth, have continued their work with renewed purpose.

Also read: Amitav Ghosh on the Indian exodus from wartime Burma and people as battlegrounds

This resilience, combined with the rise of citizen journalism, has allowed independent reporting to persevere — and even thrive — amid tyranny. “Despite the immense challenges Myanmar’s independent media have faced since the coup, private news outlets have grown and diversified in exile, along with their audiences,” remarked Margarite Clarey, media relations lead for Asia at the International Crisis Group, in one of her recent reports.

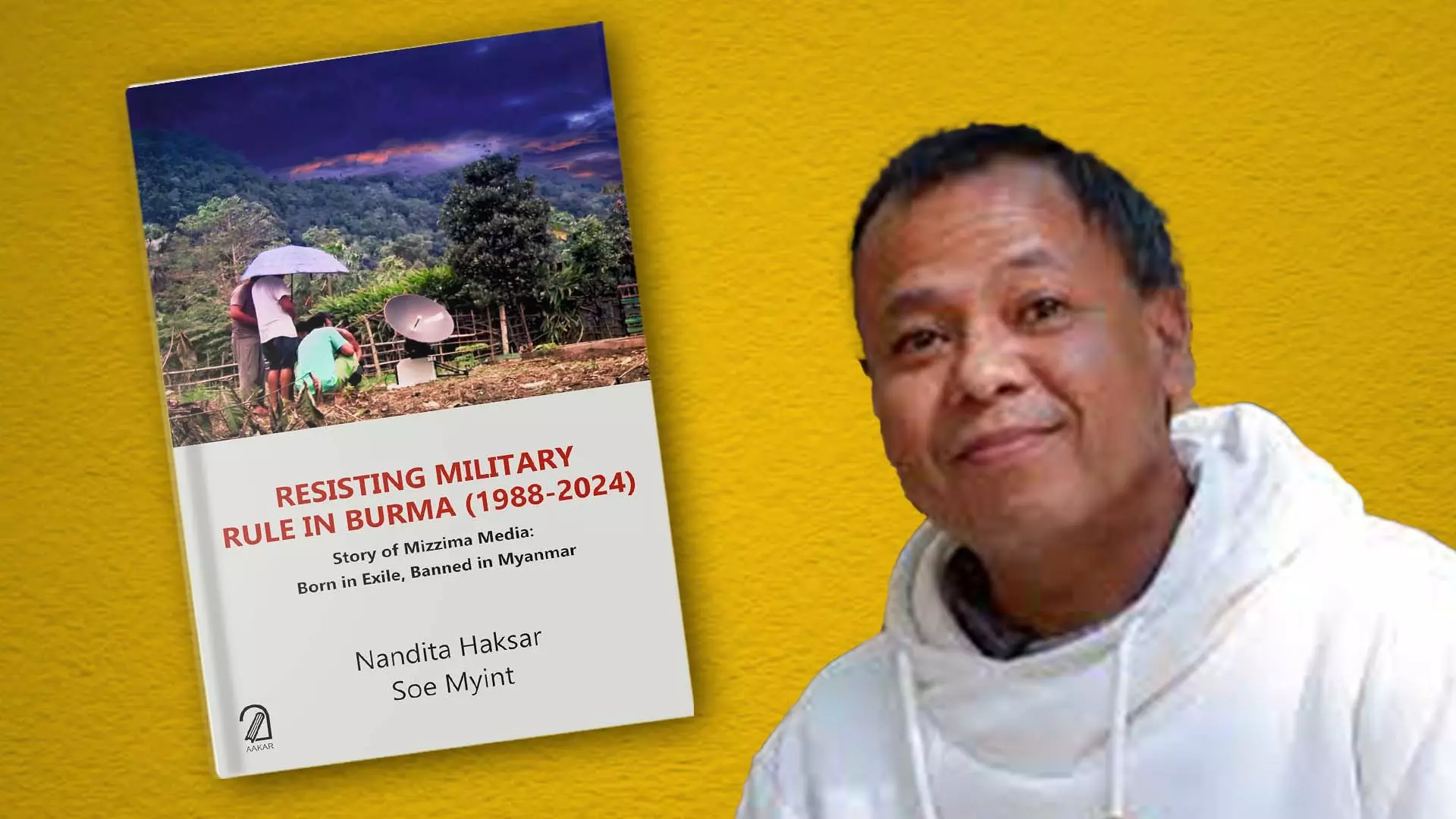

Soe Myint, the founder and chief editor of Mizzima News, has written a book on Mizzima, Resisting Military Rule in Burma (1988-2024); Story of Mizzima Media: Born in Exile, Banned in Myanmar, along with Nandita Haksar

“We had shifted a broadcasting team into the safety of the jungles in Karen State a week after the coup so that we could continue reporting on what was happening in various parts of the country,” recalled Soe Myint, the founder and chief editor of Mizzima News.

The Karen State in the eastern part of Myanmar, bordering Thailand, is largely controlled by the Karen National Union (KNU), an ethnic militant group fighting for an independent homeland.

Narrating the great escape, Myint told The Federal, that initially seven of them left for Karen State with equipment comprising two large cameras, three desktop computers, three laptops, a wireless video streaming encoder (LiveU), a switcher, a production control unit and audio mixers.

On February 7, 2001, Myint, along with a colleague, drove in a car while the others embarked the around 150 kilometres journey from Yangon to Karen state capital Hpa-an on a hired bus. The alibi for the trip to negotiate police and military checkpoints was that they had gone to Yangon to shoot for a film, but could not do so due to the coup, and hence they were returning home.

They acquired fake identity cards and COVID passes. As anticipated, the team was stopped and frisked by the security personnel on the way. Nothing amiss was found and they could reach their first port of call after dusk.

Next morning, a member of the KNU made arrangements for the team to travel from Hpa-an town to the jungles controlled by the outfit’s brigade 7 along the Thailand border to set up Mizzima’s headquarters in exile.

“Life in the jungles presented all kinds of challenges. In the rainy season, we had to wade through mud to our studios; and while broadcasting thousands of insects would be attracted by the lights and we had no means of dealing with the shadow they cast on the screen,” Myint wrote in a book on Mizzima — Resisting Military Rule in Burma (1988-2024); Story of Mizzima Media: Born in Exile, Banned in Myanmar — he co-authored with Nandita Haksar, a noted human rights lawyer and writer from India.

Also read: As Myanmar army loses control, what options does India have?

Myint said their broadcast station was just a small room inside a bamboo structure covered with a blue plastic sheet and the anchors read news from small self-made studios.

Apart from a safe place outside the control of Junta, the Mizzima needed a generator for electricity in the jungle and Thai SIM cards. “Later, we bought a satellite internet terminal called Explorer BGAN to use as an emergency internet provider when our Thai SIM cards did not work,” Myint said.

Men reading newspapers on the street of Yangon, Myanmar. Archive photo: iStock

Some media organisations like Than Lwin Khet, a Burmese-language digital news portal, escaped to Thailand with their logistics.

When operating in Myanmar ceased to be an option after the coup, Than Lwin Khet’s team smuggled their newsroom laptops, cameras and accessories out of Yangon in seafood trucks, according to ICG’s report. “Subsequently, they relied on priests and cattle traders to get them across the border to safety,” it said, “They now have around ten reporters in Thailand and five who continue to report covertly from inside the country, despite the risks.”

Around 60 media organisations are now operating outside Myanmar, with more than 1,500 journalists in their ranks, according to the ICG. Apart from news despatches sent by their under-cover reporters from epicentres, the exiled media outlets source their information from social media posts and inputs of citizen journalists.

Since the coup, Mizzima TV has been broadcasting from 6 am till late night. It has now even diversified into more media platforms so that even if one platform was not available, the people could access the news and information through another platform.

Myint is also instrumental in setting up the Mizzima Media Training Institute inside the jungle. From a media outlet founded in exile in New Delhi in August 1998 with a laptop and public phone booth, life has come full circle for the Mizzima, and so is for its founder Myint, a cancer survivor.

Myint’s entry to India was no less, if not more, unconventional and courageous than escaping with a television station from under the nose of the junta. He, along with a fellow student leader, hijacked a Thai Airways passenger flight, using a fake bomb made with soap and wires and got it diverted to Kolkata (then Calcutta) way back in 1990.

Also read: India, US appear to discount possible collapse of Myanmar military rule

The intention, he said, “was to draw India’s attention to our struggle with a hope that Indians would support our movement for democracy.”

During his stay in India, he and a group of other Burmese journalists launched the Mizzima and ran it in exile for about 14 years before moving to Myanmar in 2012, only to be exiled again.

The story of plane-hijacker-turned journalist Myint and his dream project Mizzima perhaps offer a more vivid and nuanced understanding of the turbulent history of Myanmar than any other grand narratives or political accounts. Theirs is the story of Myanmar’s relentless struggle for democracy and freedom.