- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

No time for rest or relief: The enormous hardship of garment workers

With a calm demeanour Rukmini VP, president and founder of the Garment Labour Union (GLU) from Bengaluru, listens to at least seven women describing the “abuse and dreadful shopfloor conditions” endured by them in one of the hundreds of sweatshops located across Karnataka.More than 4.25 lakh people work in garment factories in the southern state. Around 2.75 lakh are employed in...

With a calm demeanour Rukmini VP, president and founder of the Garment Labour Union (GLU) from Bengaluru, listens to at least seven women describing the “abuse and dreadful shopfloor conditions” endured by them in one of the hundreds of sweatshops located across Karnataka.

More than 4.25 lakh people work in garment factories in the southern state. Around 2.75 lakh are employed in various factories in Bengaluru. Between 85 to 90 per cent of the workers are women. These “high numbers" do not ensure their empowerment, safety and well-being. Rather their gender, poverty and caste further add to their plight.

Fifty-year-old Rukmini, who herself worked as a factory worker stitching apparel for global brands before becoming an activist, says, "I decided to work a few months after giving birth to my first child, a son. I was 19. I worked for 17 years. I had some horrible experiences. I faced harassment and verbal abuse which increased many folds after I started activism. I was also suspended from the factory."

A train of trouble—from home to work

Rukmini, who set up the GLU, a trade union body, adds, "Misfortunes like mine (some even worse) are endemic to the women workers. Garment factories are infamous for paying abysmally low wages, having long and strenuous working hours and women employees facing frequent abuse and sexual harassment, to name a few. The repeated violation of women workers' rights has been normalised.”

Their agonies do not end at their workplace. It extends to their homes, where they have to cook, clean, bear and nurture children and face violence from their spouses. Most of these garment workers come from rural belts of Karnataka (part of intra-state migration), whose families are landless and work in the informal sector. The poor financial condition of their families forced them to drop out of school at an early age.

Afterwards, most of them are married off as child brides. Rukimi herself had a child marriage when she was 15. So was Lakshmi TN, 33. Lakshmi works in a cramped factory on the second floor of a dilapidated building in Bengaluru's Whitefield. She stitches dresses for girls.

“I was 16 when I got married. My father ran a grocery shop in Tumkur (around 70 kilometres from Bengaluru). Between my two brothers and me, my father decided to support my brothers' education because they were his male heirs. I wanted to study and become a lawyer. But I was destined to work in a factory," says Lakshmi.

An industry built on women’s trauma

After marriage and two children, the 33-year-old joined a factory to support her family income. Since then Lakshmi's life has become a saga of unending physical toil. And on top of that the abuse which she has to endure at her house and workplace makes it "unbearable". "I wake up every day cursing my life. I have no choice but to endure the trauma," she adds.

These women labourers work around 16 hours a day.

Supriya RoyChowdhury, visiting professor, National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, recalls hearing cries for help similar to Lakshmi's from garment factory workers while authoring the report, "The home and the world of work: examining the intersections of gender, labour and capital in Karnataka's apparels export industry.”

One woman told RoyChowdhury she cursed god for making her go through her daily struggle. “It leaves a great deal of psychological and physical pain among the women. They suffer from time poverty, lack of attention, physical exhaustion and extreme dilemma,” adds the professor.

Some of the findings of RoyChowdhury's report reiterate the horrific working conditions of garment workers. It also suggests that the fancy clothes worn and exported by India are systematically tearing off the dignity and human rights of these marginalised women. The successive governments seem to be non-committal to ensure the protection of the workers’ rights.

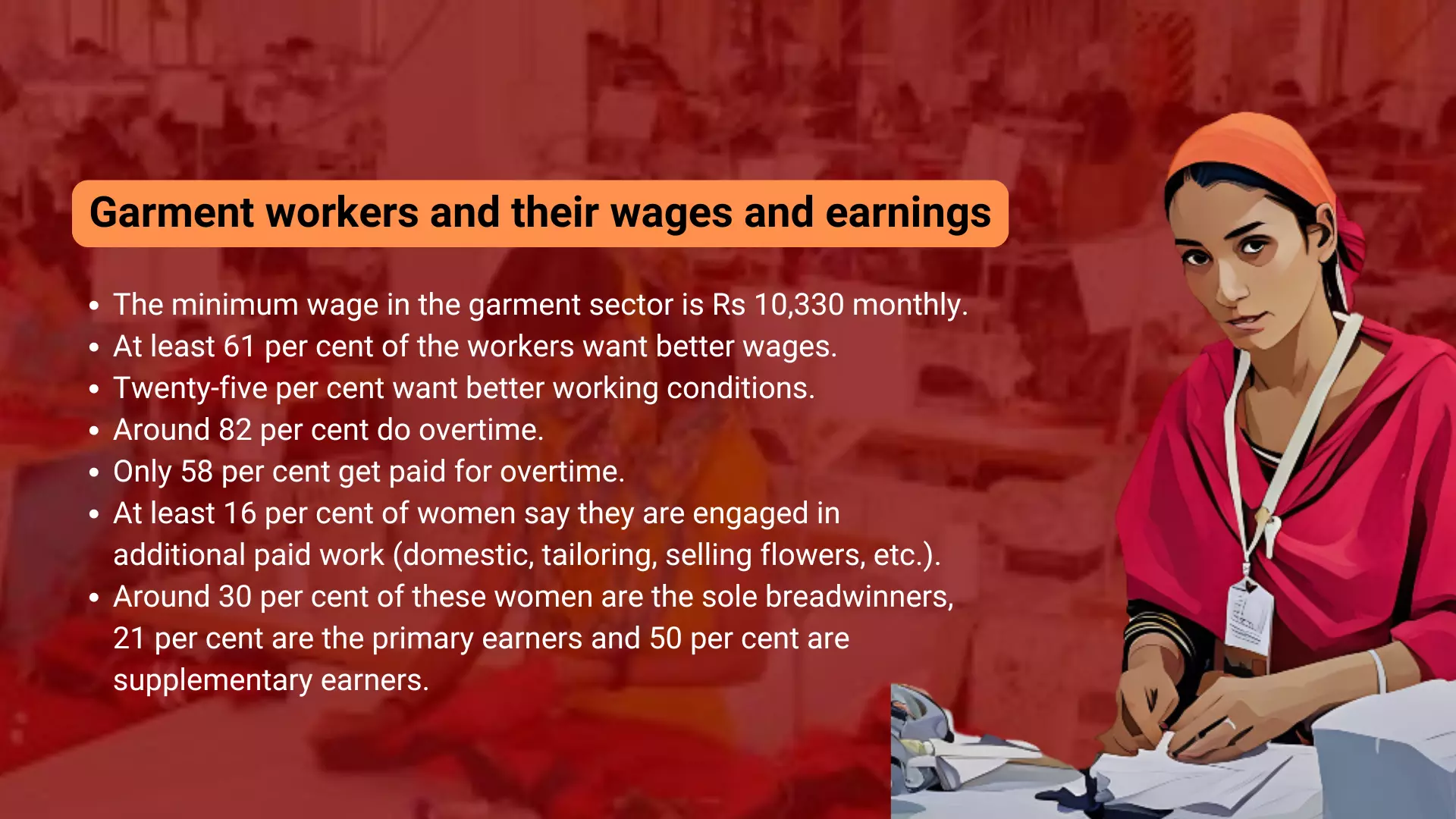

“The minimum wage in the garment sector is Rs 10,330 monthly; other sectors pay higher for skilled/unskilled workers. At least 61 per cent of the workers want better wages and 25 per cent want better working conditions. Around 82 per cent of the respondents say that they do overtime and only 58 per cent get paid for overtime. At least 16 per cent of women say they are engaged in additional paid work (domestic, tailoring, selling flowers, etc.). Around 30 per cent of these women are the sole breadwinners, 21 per cent are the primary earners and 50 per cent are supplementary earners," stated the report.

The two-year report (between 2022 and 2024) was based on "intensive interviews" with at least 200 women in Bengaluru and Mysuru to uncover multi-layered challenges they encounter at work and home. It is not the first to document either the poor working conditions, low wages or gender-based violence in the fashion industry across the country, but RoyChowdhury and her team for the first time considered highlighting how these female labourers live their lives in their homes (which again are full of hardships).

Cividep India, a Bengaluru-based organisation that works for workers' rights and corporate accountability, and Stitch, a global network working for the human rights of workers in the textile and garment industry, supported the report.

The 2015 report, Insights into working conditions in India’s garment industry, by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), states workers are subjected to verbal abuse daily. “Sexual violence or harassment of women is reported by one in ten of all workers but nearly one in five women. There is thus abundant evidence of workers, of both sexes but especially women, being subject to threats and penalties during the employment phase, and of working under duress,” adds the report.

Gender issues are widespread in the garment sector

India is the world’s second-largest garment-exporting country. At least 45 million people work in the textile and garment industry in the country. It is the third-largest employment-generating sector. Delhi NCR, Bengaluru and Tirupur are the three main garment-producing hubs.

As more and more women — most of whom are school dropouts and unskilled/semi-skilled — joined the sector, the garment industry witnessed an increase in feminisation (60 to 70 per cent women workforce). Academicians and activists say so is an increase in discrimination and abuse of human rights within the four walls of a factory stitching thousands of readymade clothes at a time.

“With high demand throughout the garment industry, there is a great deal of pressure on factories to produce a lot. This means that many workers are forced to stay late and work long overtime hours which often are unpaid,” states Fair Wear, an organisation that works to improve labour conditions in the garment industry.

“Sexual harassment remains a major challenge as well and generally goes unreported. While certain measures exist, the reality is that most garment factories do not have functioning mechanisms in place to ensure that gender issues are being addressed and dealt with,” adds Fair Wear.

Existential crises

It has been three decades since Savitri RM has worked in various garment factories. Now, she works for a clothing manufacturing unit in Bengaluru’s Marathahalli.

As she gets a paltry sum of Rs 10,000 a month, Savitri, in her mid-fifties, also works as a domestic help in a house close to her factory. “I also work as a housemaid. I have been forced to take a second job because of the rising prices of essential commodities. Before going to the factory, I finish my cleaning and sweeping job at a house early in the morning. It helps me to earn Rs 1,500 extra every month.”

Earlier, Savitri was working in a garment factory in Peenya, the garment industry hub of Bengaluru, before it was closed. “My first pay package was Rs 300 per month. Now, I am earning Rs 10,000. My husband works as a security guard at an office. He earns Rs 15,000. If I stop working, we won't be able to survive as prices of essential commodities are rising drastically. We stay in a one-room rented accommodation. It costs us Rs 8,000 a month."

Normalisation of abuse and violence

Apart from her daily struggles, Savitri is angry that "abuse and violence" have become a part and parcel of a woman labourer's life. She has been a victim of sexual abuse by a factory manager. Savitri wants to forget the "horrifying episode" but cannot. "Nothing has changed. The abuse of women continues. We come to work but we pay with our dignity and self-respect."

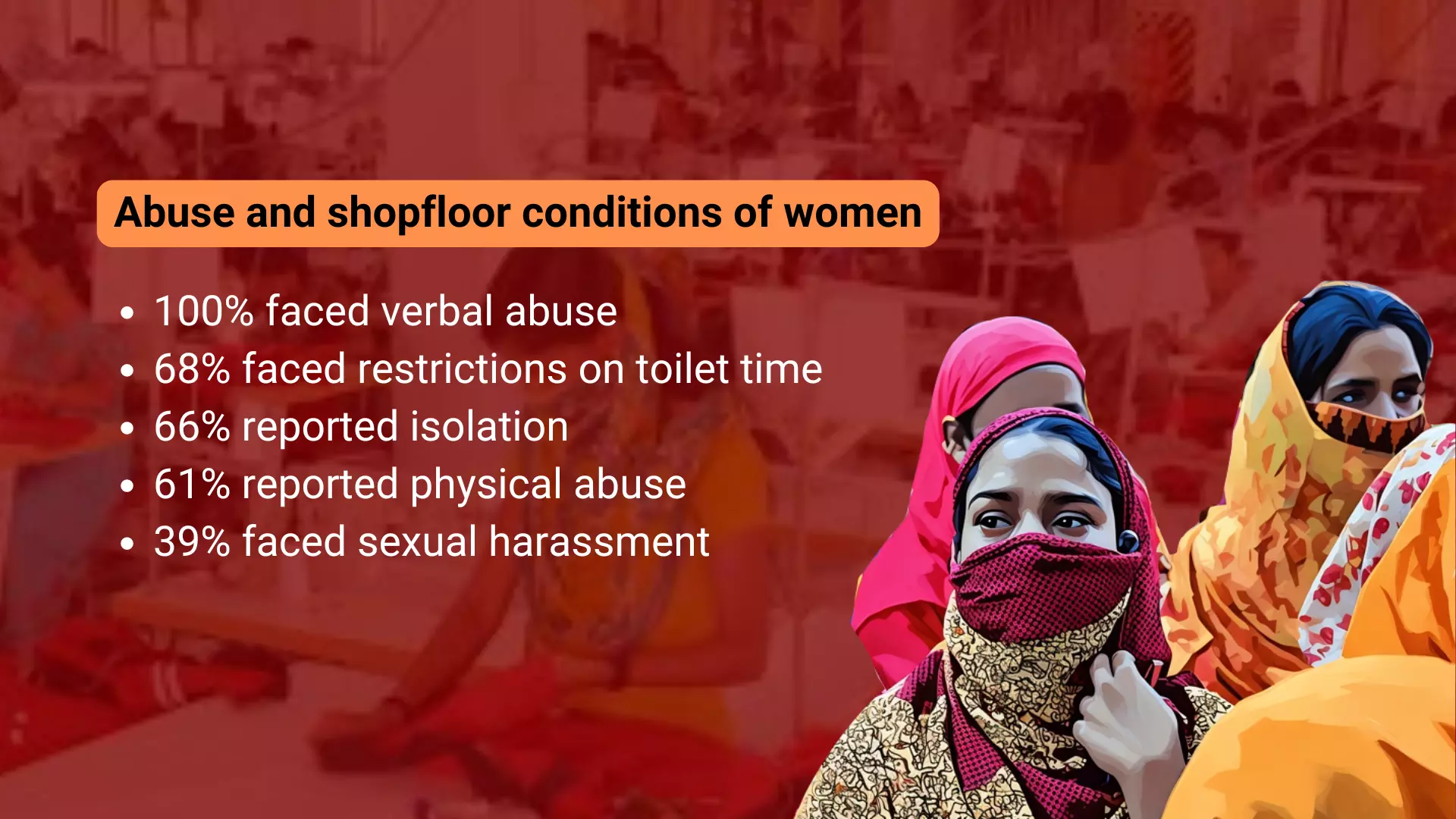

In the report authored by RoyChowdhury it was found that 39 per cent women faced sexual harassment, 61 per cent physical abuse, 66 per cent isolation, 68 per cent restriction on toilet time and 100 per cent verbal abuse.

Deepika Rao, executive director of Cividep India, insists the stories of garment labourers must be told repeatedly to help address their issues.

"These women come from poor families. They have no savings and work extremely hard but towards the end (of their career) they are left with nothing (because of violations of anti-labour laws by their employers)," she adds.

RoyChowdhury highlights the negligence (or systematic understanding between the state and the capitalistic forces) on the part of the government for not ensuring women workers get their dues.

“The state is complicit in the production of a disempowered female workforce. In a sense, the state is standing between capital and worker, and while providing work to the workforce, the kind of work being provided is hugely disadvantageous to the workforce,” she says.

"Weak regulation of global supply chains in garment production and exports contributes to exploitative conditions. The industry relies on a low-wage, low-skilled, migrant workforce from historically marginalised tribes and communities," she adds.