- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Why the death of a bird in his rehearsal space made theatre personality Prasanna give up direction

A pioneer of Kannada theatre, Prasanna has not only stalled what was to have been his latest play, 'Roko', but in an exclusive interview to The Federal announced his decision not to take up further directorial work, explaining the tragic circumstances which led him to this 'sacrifice'.

“One tragic moment altered the course of my life,” said Prasanna, talking to The Federal earlier this month. “No logic, no rationalisation will make me change my mind.”In an exclusive interview to The Federal earlier this month, the playwright-director shared his resolve to give up theatre direction, a decision, he added, he was yet to formally announce to the world.A pioneer of...

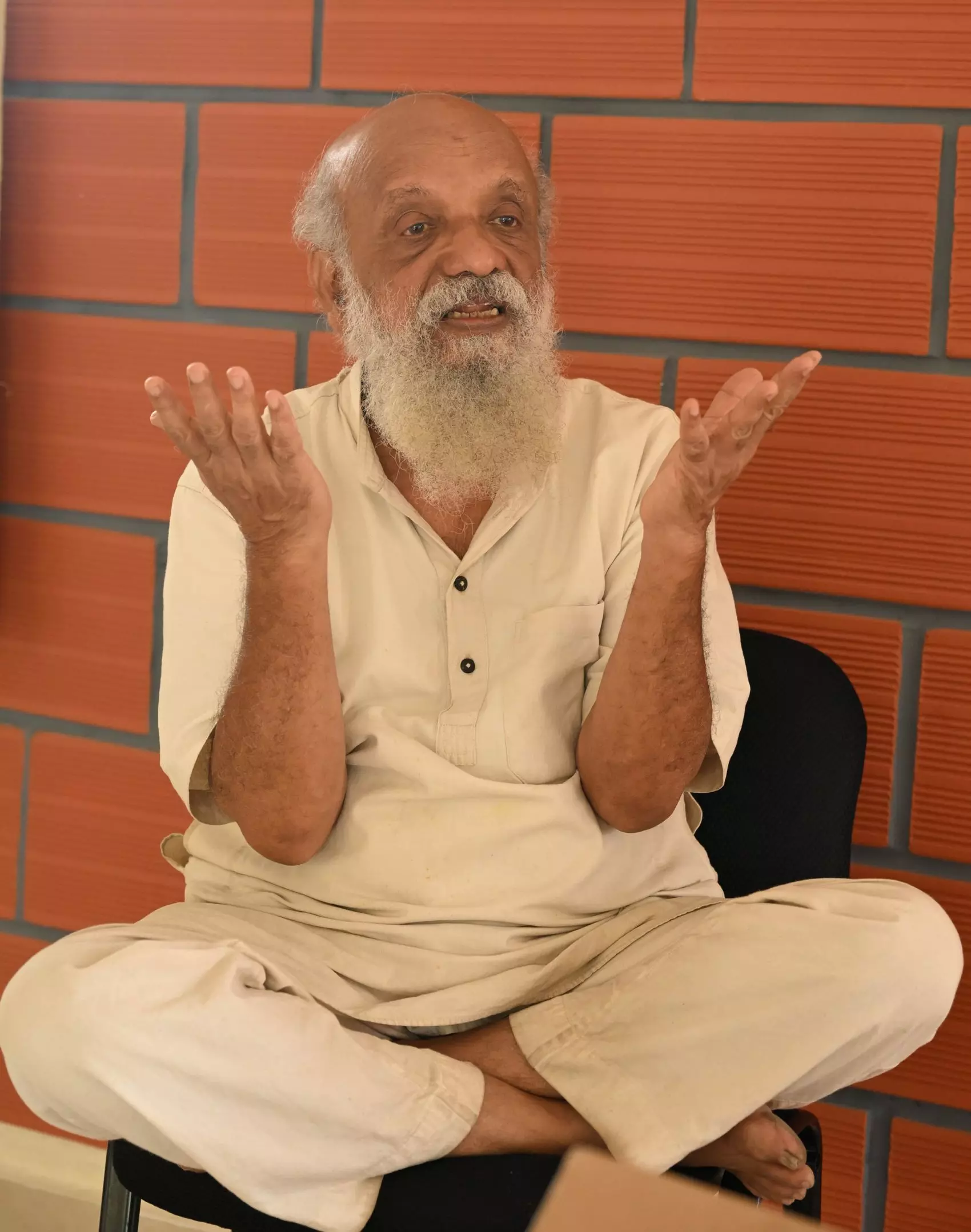

“One tragic moment altered the course of my life,” said Prasanna, talking to The Federal earlier this month. “No logic, no rationalisation will make me change my mind.”

In an exclusive interview to The Federal earlier this month, the playwright-director shared his resolve to give up theatre direction, a decision, he added, he was yet to formally announce to the world.

A pioneer of modern Kannada theatre and among the key figures behind Samudaya — a movement born in 1975 in reaction to the Emergency declared by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to use theatre as a cultural expression of democratic upsurge and the yearning for radical change — Prasanna’s decision to give up theatre direction was triggered by the death on set of a bird which had flown in while he was at the rehearsals for a new play.

“The name of the play was ‘Roko’, which in Hindi means ‘Stop’. It was aimed against war and violence. The protagonist was a little bird and the antagonist was the Hindu deity Krishna, who served as the arbiter on behalf of humans in a terrible war. Pitted against him was a bird that had laid eggs on the war ground of Kurukshetra [as mentioned in the epic Mahabharata], and was stretching every feather of its wing to stop the war.”

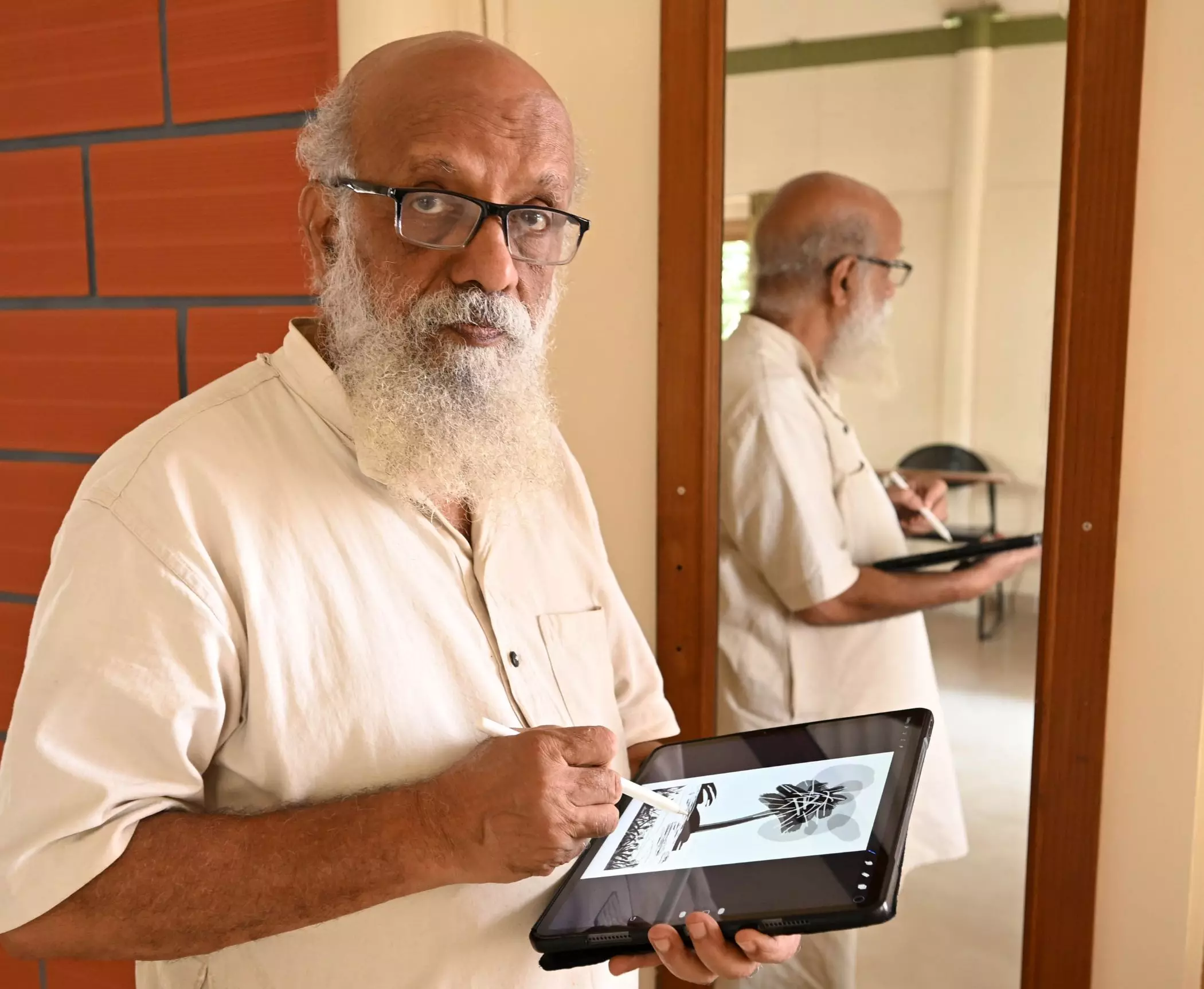

A multi-faceted talent, Prasanna had been holding an exhibition of his digital artwork at the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishad in Bengaluru at the time of the interview, and in between talking to The Federal, was walking among the display, now and then stopping to point out an exhibit or share some detail about the works.

Prasanna sketches on his iPad. Photo: K Bhagya Prakash

Continuing with his narrative about the play, he added: “One day, during rehearsals, something terrible happened. Onto the rehearsal space — the analogue of the war theatre where actors were finding their martial tread — a bird flew in. Confused and panicked, it started making desperate efforts to find a way out. The actors were initially amused by the presence of the bird, an emblem of the play itself, and by its staccato twittering.”

Talking about his own reaction to the sudden appearance of the bird, Prasanna continued: “As for me, I interpreted the bird’s streaking across the high-roofed hall as reconnaissance for a cosy corner to build a nest, or perhaps, [a search for] a refuge from a predator outside. I did not realise at the time that the bird was finding itself trapped, unable to find its way out, despite the windows and doors of the rehearsal hall being open. That day, we left as usual after rehearsals, assuming the bird would be gone by the time we returned.”

The team was, however, in for a shock the following day.

“The next morning, I found an actor holding the bird in his palm. It was too weak to fly by then. The actor gently placed it on the ground, placing a boiled potato and some water in a bowl in front of it, coaxing it to eat and drink. But the bird would touch neither and died soon after.”

Also read: Why the SIR's launch in Bengal on filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak's birth centenary is a profound irony

Prasanna says he found it hard to forget the underlying desperation in the bird’s twitter, which he and the team had failed to discern then as the cries of a creature in despair. They had also failed to spot the urgency in the bird’s fleeting movement across the hall, noticing only the gracefulness of its flight.

“It was a moment that prompted me to not only end the ongoing production, but also to decide to not take on any future directorial work,” Prasanna explained.

Elaborating on emotions that the bird’s death caused in him, the playwright-director continued, “We had believed God had sent the bird to amuse us with its song and dance. But the poor thing found itself trapped. Although we kept the windows open and attempted to shoo it out, our actions must have caused it greater alarm, prompting it to flit from one metal girder to another, until it was physically exhausted.”

Prasanna added that in that moment he couldn’t get rid of the feeling that God had sent them a message in the form of the bird and its destiny — providence had turned its back on them.

“Look at it this way. The bird got trapped. But aren’t we trapped, too? Trapped by an artificial world that we have built around us? Of roof and walls; of concrete, metal and glass? We believe we have built ourselves better nests using science and technology. All that we’ve done, however, is to trap ourselves in cages of concrete and steel,” he reasoned.

Prasanna in conversation with The Federal. Photo: K Bhagya Prakash

Returning to the subject of his decision to stall the play and not take up further directorial work, he added: “Of course, it was a terrible sacrifice for the actors. After all, I am an old man, well past retirement age [how old is he?]. But they are young. They had invested hard work in the play. I told them their sacrifice would weigh much higher in establishing the truth than mine. I told them I shall always be available in future to guide them. They have the text of the play with which they may do as they please without distorting the truth. The story that underlies the play was told to me three decades ago by Professor Ram Gopal Bajaj [a theatre director and academic]. He, in turn, had heard it from the poet Agyeya [Sachchidananda Hirananda Vatsyayan, pen name Agyeya].”

Also read: Why ongoing Kannada Sahitya Paris

Asked whether his decision would be detrimental to theatre, already in attrition from digital entertainment, Prasanna said: “One thing needs to be stated here categorically. There is a wrong notion that plays are written by a grand individual called a playwright. One who sits secluded inside a room, brooding over the idea and eventually putting it down on paper, a process supported by inspiration? That notion is wrong.”

He added: “A play is action. It is, of course, dialogue. But dialogues stem from action. There is a written document, yes, the one that contains the spoken word, which is written down by a creative person. But that person’s creativity stems from an acute participation in theatre and life. All good plays have always been written in this fashion. Only bad plays get written by an individual who arrogates to himself grand ideas of theatre in isolation. A play in truth is constructed for the theatre and through active collaboration with actors. Metaphorically speaking, a play gets written on the ‘battlefield’ of theatre.”

Prasanna’s decision must not surprise us. The theatre icon has previously too been known to adopt an unrelenting attitude on issues. In 1984, Girish Karnad’s play Tughlaq, directed by Prasanna, was to be performed at the Festival of India in London. It was dropped at the last minute, purportedly for political reasons [the play is a critical look at Nehruvian ideals of a socialist society]. Theatre practitioners across the country rose in protest. Well-meaning among them suggested to Prasanna that he make a representation to the authorities. But Prasanna stated, “I will do no such thing,” choosing to stand his ground.

Before this, in the early ’70s he had dropped out of his doctoral programme at IIT Kanpur to pursue his passion for theatre and could never be prevailed upon to return. He chose the periphery of mainstream theatre in his work, remaining critical of modernity and espousing Gandhian values. Indeed, Prasanna may even be seen as bordering on the Luddite in his anti-technology stance.

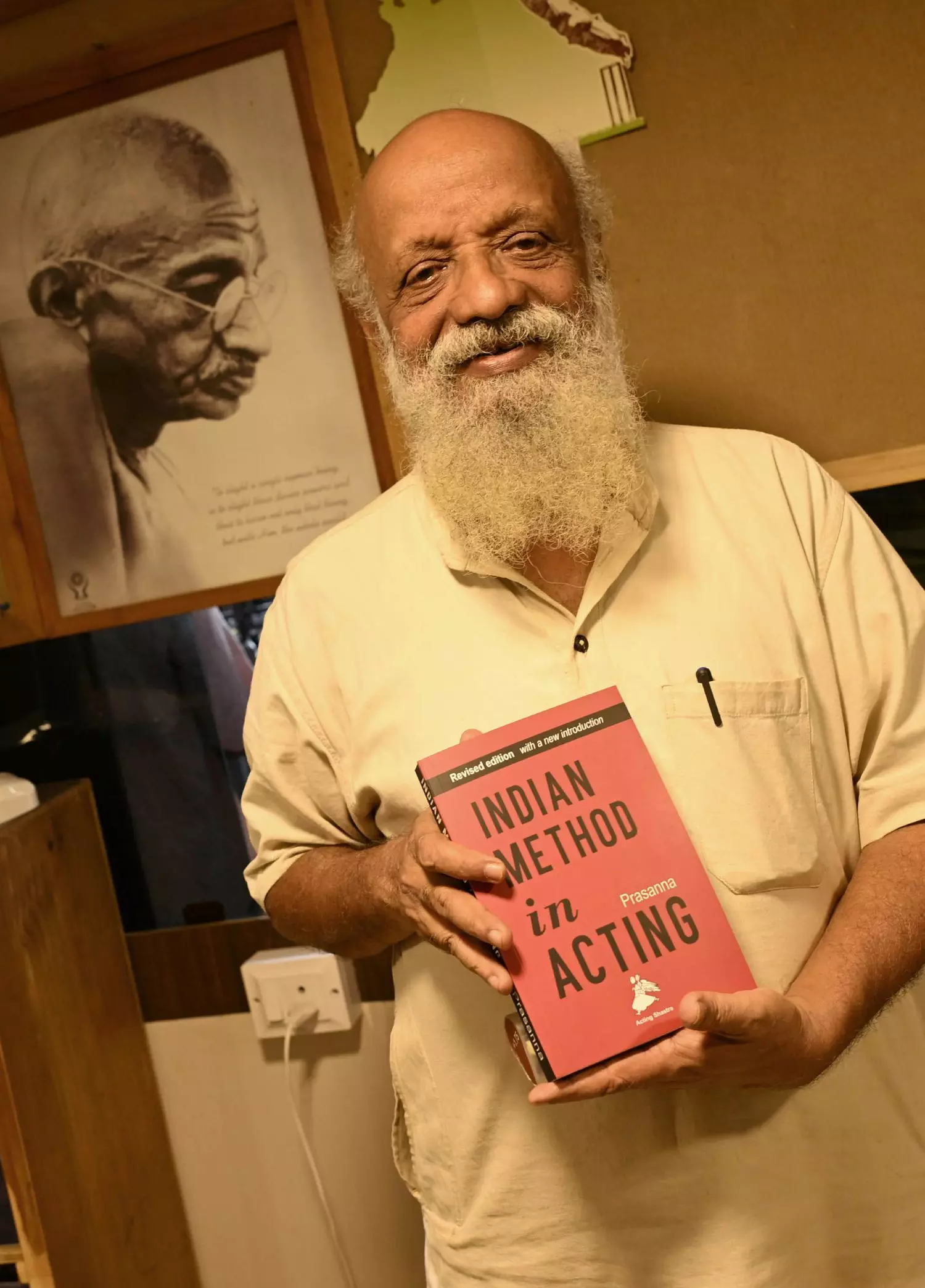

Prasanna hold a book authored by him. Photo: K Bhagya Prakash

While Samudaya completed 50 years this year, continuing to use the stage to spread socio-political awareness, beyond theatre, Prasanna has been the promoter of Charaka, a rural women’s handloom collective established in Karnataka’s Heggodu more than 28 years ago, and laid the foundation of several other rural initiatives such as the Kavi-Kavya Trust, a publication platform and Desi Trust, for empowering rural women.

“I am drawn to artisans who live by the toil of their hands; I prefer that to the toil of the intellect,” he said.

Also read: Samudaya at 50: Why Karnataka’s theatre collective must reinvent to stay relevant

Valmiki, remembered as the creator of the Hindu epic Ramayana, once seeing a happy pair of birds hit by a hunter’s arrow, is said to have, burst forth with the couplet, “Mā niṣāda pratiṣṭhāṃ tvamagamaḥ śāśvatīḥ samāḥ, Yat krauñcamithunādekamavadhīḥ kāmamohitam [O hunter, may you never find lasting rest, as you killed a bird couple in love].” The couplet is considered the first shloka of Sanskrit literature.

Drawing a parallel between the cursed hunter and the death of the bird in their rehearsal hall, Prasanna said: “We began to feel that in dying this bird was demanding a sacrifice from us. We were the representatives of the 'terrible species' called humans. It asked us to make amends not by enacting the play, which would culminate in the victory of the bird, but through existential enactment by quitting the battle ground, which, for us, was the theatrical space, the rehearsal space.”

He added: “I took it as a personal message and decided that I must sacrifice my theatre work. Only by doing this would I be responding in full authenticity to the message that the bird gave us. I wish to be authentic.”

The playwright-director has a deep respect for the Ramayana, “written by a Shudra [according to some accounts Valmiki was born a Dalit]”.

“Ramayana is the greatest epic of India and the world. It is a theological text for India and Hinduism. Shudra saints actually led a revolution. They are the ones who tried to save Hinduism from becoming Brahminical. Their quest was always socialist, egalitarian, and compassionate. Though I dislike the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] for ideological reasons, the BJP has successfully brought the Ramayana to the mainstream. But I hate the politicisation of the epic, distorting Rama to consolidate its vote bank”. Prasanna stated.

An awardee of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, he has directed plays for the National School of Drama (Repertory), Ninasam (Sri Neelakanteswara Natyaseva Sangha, founded in 1949 in Heggodu), Rangamandal (Bhopal), Rangayana (Mysuru), and other theatre organisations. Plays directed by him include Dangeya Munchina Dinagalu, Ondu Lokada Kathe, Galileo, Tughlaq, Shakuntalam, Gandhi, Fujiyama, Lal Ghas Per Neele Ghode, Uttara Rama Charita, Kadadida Neeru, Thaayi, Haadu Meerida Hadi, Hamlet, Road to Mecca, Cupid’s Broken Arrow and others.

He has written two major works on theatre — Indian Method in Acting, published by NSD and Acting and Beyond, published by Akshara Prakashana.

Over the past five decades, Prasanna has remained the restless conscience of Kannada cultural life. “I am living in terrible, restless times. Restlessness is not a negative thing; Buddha, Basava, Gandhi and Ambedkar have also lived in the kind of restless times,” he said.

His presence embodies a rare moral consistency, bridging the worlds between production and performance, thought and action, art and activism. He is a mentor to younger theatre practitioners. He holds that art must serve society, without being didactic, without taking recourse to easy definitions.

In an age that measures success in market terms, Prasanna’s journey is rooted in the conviction that ethical living is the highest form of art and continues to inspire those who believe that social transformation begins not in slogans, but in lived practice.

While his decision not to take up direction any more is sure to come as a blow to colleagues in the theatre, The Federal was unable to get their reaction since Prasanna is only voicing his decision in this article and has not made any public announcement.

Also read: Why NSD fee for acting course in Mumbai has raised concerns of the institute serving the elite

For the artiste, however, the question is “what next” — Prasanna is too creative a person to imagine living in inactive retirement.

A few years ago, Prasanna got an iPad, which, he says, allowed him to create drawings like a woodcut, a relief printing technique. He took his iPad on his travels and created art on the go. ‘Playing with Life’, a collection of abstract and representational works, pencil sketches of characters from his five-decade theatre career, was the result of this new obsession. The collection was on exhibition at Bengaluru’s Karnataka Chitrakala Parishad between October 31 and November 2.

“My creativity is visually driven. It is the case with me as a performer, as an actor, as a trainer,” Prasanna said. He had earlier designed fabrics and prints at Charaka. “This has been inside me,” he said, a smile brightening up his face, even as the discussion moved from the sombre to the sublime.

Like all his creative endeavours, however, the exhibition too has an underlying social cause, organised to raise funds to support his social activism, in this case for the Indian Institute for Educational Theatre.

“I intuitively embraced theatre all these years. I will continue to be in the theatre through mentoring students. But I will not direct play,” he repeated emphatically, returning to the subject which had started the interview.