- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Real reason why Kashmir feels close to Iran

Earlier this month scores of Indians studying in Tehran and other Iranian cities returned to their homeland as Israel launched unprovoked military strikes at Iran. That a bulk of these students were from the Kashmir Valley triggered ‘explanations’ in the media for why Iran attracted so many Kashmiri students.Of the two broad strands proffered, the first was the inexpensive cost of...

Earlier this month scores of Indians studying in Tehran and other Iranian cities returned to their homeland as Israel launched unprovoked military strikes at Iran. That a bulk of these students were from the Kashmir Valley triggered ‘explanations’ in the media for why Iran attracted so many Kashmiri students.

Of the two broad strands proffered, the first was the inexpensive cost of education, medical courses in particular; compared to the exorbitant fee in India while the other was Iran being a Muslim-majority country. Some media outlets went a step further to specify Iran’s Shia majority.

As per some estimates, while a medical degree from an Indian varsity could cost anywhere up to or even more than Rs 1 crore, the cost for the same course in Iran, including expenses towards accommodation, food and travel, falls well within Rs 30 to 40 lakh. While affordable cost of education in Iran compared to India’s prohibitive fee structure is undoubtedly a valid explanation for Kashmiris heading to the Middle Eastern nation, it is the second reason that is grossly off the mark.

“Those claiming that Kashmiris go to Iran because it is a Muslim majority or a Shia majority country do not know that a much larger number of Kashmiri students has been going for the same studies to Russia since the 1980s. One could even say becoming a doctor is almost an infatuation in Kashmir; it far outranks engineering, MBA and other degrees, but the cost of pursuing a medical course in India is prohibitive and so is the admission process, which forces Kashmiri students to look at better, easier and cheaper options abroad. Iran being an Islamic Republic has nothing to do with this,” GN Var, president of the Private Schools Association of Jammu and Kashmir told The Federal.

Var says till the 1990s, it was largely Kashmiri Shia Muslims – only a fraction of Kashmir’s overall Muslim population – who would go to Tehran or other Iranian cities like Qom, Shiraz or Mashhad for theological studies “not only due to the religious significance that these places have for Shias worldwide but rather for the shared kinship we have had with Iran for centuries, which isn’t limited to religion but spans across culture, language, literature, architecture and crafts”.

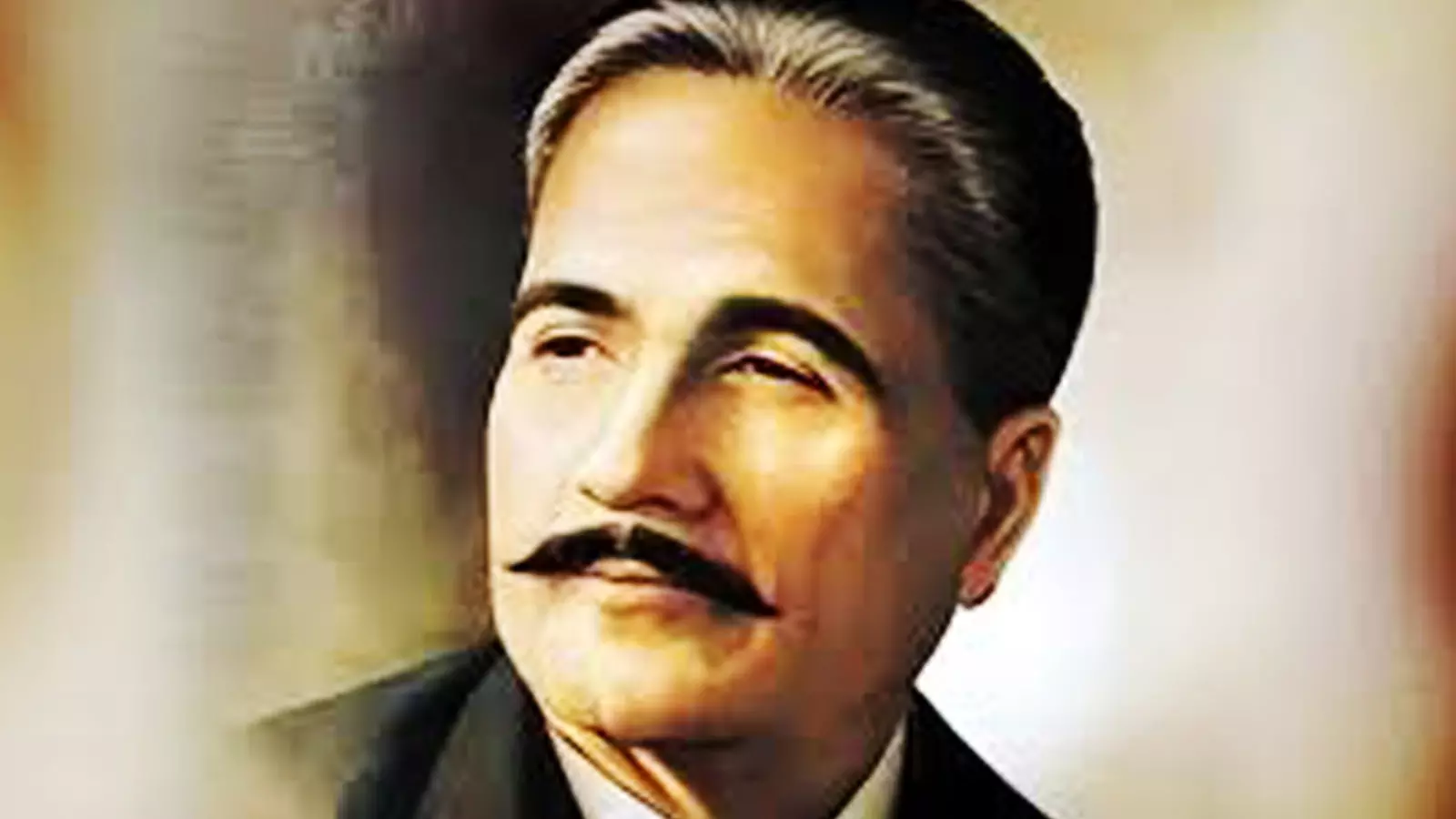

This kinship that Var speaks of is, perhaps, best exemplified in the immortal moniker Allama Iqbal coined for Kashmir – Iran-e-Sagheer (Little Iran). Srinagar-based historian, writer and cultural critic Saleem Beg believes Iqbal’s conception of Kashmir as Iran-e-Sagheer stemmed from predominantly two historical perspectives.

Allama Iqbal coined the term Iran-e-Sagheer (Little Iran) for Kashmir.

First, Kashmir had shared an over a millennia-long bond with Iran and the wider Persiannate, including much of present day Middle Eastern and Central Asian nations, through trade and socio-cultural exchanges predating even the foundation of Islam. Second, and more importantly, the transformation Kashmir witnessed in every walk of life, including the voluntary and not forced conversion of its Buddhist and Hindu population to Islam, since the 14th Century.

Lhachen Rinchan, the Buddhist founder of the first Sultanate of Kashmir, is said to have converted to Islam towards the end of his brief three-year reign in 1323 AD, inspired by the visiting Iranian Sufi saint Sharfuddin Rahman ‘Bulbul Shah’. Around six decades later a stronger foundation for an enduring Iran-Kashmir bond was laid with the arrival of another Sufi philosopher from Iran, Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani. Revered with honorifics such as Shah-i-Hamadan (king of Hamadan), Amir-e-Kabeer (Great Commander) and Ali Sani (the Second Ali), Ali Hamadani had arrived in Kashmir around 1383 AD when Qutb-ud-din Shah of the Shahmiri dynasty ruled Kashmir.

In popular Kashmiri discourse, this was Hamadani’s third and last visit to Kashmir. Beg, who retired as Director of J&K Tourism in 2006 and has since been the convenor of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), J&K Chapter, however, asserts that “historical records only give conclusive accounts of Shah-i-Hamadan’s arrival in 1383 AD”. What is undisputed, though, is Hamadani’s contributions to and impact on Kashmir.

“Contrary to popular belief, Shah-i-Hamadan didn’t come to Kashmir as an evangelist. Islam had already begun to spread in Kashmir over the preceding six decades and archival records show Hamadani spent only a few months in Kashmir and then wanted to return to Persia because of his failing health. He died in Kunar (Afghanistan) on his way back. This timeline doesn’t support the popular theory of Kashmir adopting Islam under Hamadani’s influence. The more widespread but peaceful conversion to Islam began in the years that followed; inspired by the teachings of Noorudin Noorani or Nund Rishi and the Rishi order of Sufis, which unlike the Qadri, Kubrawi, Suhrawardi (all originating in Iran) and Naqshbandi (Uzbekistan) Sufi orders, was indigenous to Kashmir. Hamadani’s contribution to Kashmir, though, remains unparalleled but for reasons that go way beyond evangelism,” Beg says.

Hamadani is said to have arrived with a huge Persian entourage of poets, philosophers, traders, craftsmen and people from diverse walks of life. Since he also had the ear of the Sultan, he was able to bring in people-oriented reforms in administration of Kashmir and even after he left Kashmir he wrote to the Sultan advising ways to further improve the condition of the people. Zakhirat-ul-Mulk, a manual on governance authored by Hamadani, ostensibly provided Shahmiri rulers a template for administration.

The Hamadani shrine in Srinagar.

Srinagar-based scholar, conservation architect and author of ‘Shi’ism in Kashmir’, Hakim Sameer Hamdani argues that it is in the years following Shah-i-Hamadan’s departure, that Kashmir began to realise the value of what the Sufi had left behind.

“It is through the people that Shah-i-Hamadan brought with him, including his son Mir Muhammad Hamdani, that Persia’s influence began to spread on everything Kashmir is known for today. The arts of Kar-i-Kalamdani (papier-mâché), calligraphy, khatamband (making geometrical patterns in wooden ceilings), pinjrakari (latticework), aari (needlework), all were taught to Kashmiris by the people who came with or after Shah-i-Hamadan from Iran,” Hamdani tells The Federal.

With time, as exchanges between Kashmir and Iran increased, Hamdani says Persia’s imprint on Kashmir also grew. “Food, architecture, the motifs we use in our shawls and clothes, the cultivation of saffron, the layout and design of our khanqas and shrines; anything you think of as Kashmiri today has some element of Persia; you see the influence of Isfahani architecture in our religious and historic structures, the celebration of Nauroz as the Kashmiri New Year is a direct link to Iran. Another unique practice among Kashmiri Muslims; something you will not see anywhere else in the subcontinent, is the chanting of the Awrad Fatiha (or Aurad-e-Fateh), a composition by Shah-i-Hamadan himself, which Kashmiri Muslims, Shia and Sunni alike, sing even today immediately after offering namaz at fajr (dawn),” says Hamdani.

This expansive treasure trove that Kashmiris received from Shah-i-Hamadan explains why Allama Iqbal, in his Javid Nama, eulogizes the Sufi saint thus:

Murshid-e-aa’n Kishwar menu nazeer, Mir-o-darvesh-o-salateen ra mashir

Khitah ra aan shah-e-darya aasteen, Daad-ilm-o-sanat-o-tahzib-o-deen

[Guide of the country known as Paradise; Advisor of Noble, Saints and Kings,

With his inclusive approach and expansive vision, He (Shah-i-Hamadan) has provided us knowledge, industry, culture and religion]

Among the most enduring legacies of Shah-i-Hamadan in Kashmir was the popularization of the Persian language. “The Shahmiri rulers had adopted Persian as a court language before Hamadani’s arrival but it hadn’t yet become a language of the masses. Until Hamadani’s arrival, Persian speaking people in Kashmir were not ordinary Muslims but either members of the Shahmiri dynasty or from the community of Kashmiri Pandits, which formed the bulk of Kashmiri nobility. The credit of popularizing Persian among common folk goes to the poets and philosophers that came with or after Shah-i-Hamadan,” Prof. Akhlaque Ahmed ‘Ahan’, poet, writer and chairperson of Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre of Persian and Central Asian Studies tells The Federal.

By early 15th Century, during the reign of Shahmiri sultan Zain-al-Abideen, Kashmir emerged as a major hub of Persian learning and literature not just in the subcontinent but even for scholars from the Persiannate. Abideen is known to have founded a Dar-ul-Tarjuma (school of translation) that became a centre for translating historic and religious texts, including Hindu epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as Sanskrit literary masterpieces such as Kalhana’s Rajatarangini into Persian. Similarly, Persian literature, including theological texts, was translated into the Kashmiri vernacular.

The patronage Persian received in Kashmir grew further when the Mughals dethroned the Chak rulers, who had replaced the Shahmiri dynasty, during Akbar’s reign. Iranian poets continued to arrive in Kashmir through the reigns of Akbar, Shah Jehan, Aurangzeb and the later Mughals. The grossly neglected Mazar-e-Shura (cemetery of poets) in Srinagar is recorded to be the burial ground of at least five Iranian poets (though only two gravestones remain intact today) who had arrived in Kashmir during Mughal rule. Many Persian Sufis poets who arrived and settled in Kashmir began to be revered locally; their Urs is still celebrated in the various towns of the Valley.

Beg says with time the bond between Persia and Kashmir evolved into one of rich and regular cultural exchange. “In Iran, a common folklore is that foreign dignitaries visiting Iranian rulers would be presented with shawls; the higher the station of the visiting dignitary, the better the shawl but the most important dignitaries would always be presented with Kashmiri shawls. There are also many records of the influence Gani Kashmiri (Muhammad Tahir Gani, 17th century, considered Kashmir’s greatest Persian-language poet) had on poets and philosophers from Persia and an even greater number of Persian writers drawing inspiration from Kashmir itself,” he explains.

Even in the 14th Century, around the time of Shah-i-Hamadan’s visit to Kashmir, Persian poets would make various references to Kashmir. A somewhat self-adulatory couplet from the great Iranian mystic poet Khwaja Shams-ud-Din Moḥammad Ḥafeẓ, popularly known as Hafez of Shiraz, goes thus:

Be she’r e Hafiz-e-Shiraz mi raqsand o mi-nazand

Siyah chashman e Kashmiri wa turkan e samarqandi

(Black-eyed Kashmiris and Turks of Samarkand dance in joy when they hear the poetry of Hafiz of Shiraz)

For centuries, Iran and Kashmir prospered with this seamless syncretism rooted not in religion alone but in language, culture, heritage, architecture and cuisine. “A shared religion is, at best, incidental to this kinship,” says Prof, Ahmed while agreeing that the “unwavering support that the Ayatollahs of Iran and their regime has extended repeatedly to the people of Kashmir at large and not just to Kashmiri Shias, even if it has at times displeased New Delhi, has strengthened these ties”.

In Budgam, which has Kashmir’s largest Shia population, legend has it that in early 1979 when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was set to return to Iran from exile to lead the Iranian Revolution against the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Budgam’s Syed Yusuf Al-Moosavi, the then Aga (religious leader) of Kashmiri Shias, wrote to him offering safe refuge in Kashmir in case the Ayatollah changed his Iran plans.

Khomeini had a deep connection to India, if not a direct one to Kashmir, as his paternal grandfather, Syed Ahmad Moosavi was born in the village of Kintoor, in today’s Uttar Pradesh’s Barabanki district, in 1800 AD. Syed Ahmad left Kintoor with his family in 1830 AD and after spending some years in Iraq’s Najaf finally settled in the Iranian city of Khomeyn and adopted Khomeini as the family surname. “Throughout his life in Iran, Ahmad continued to be addressed as Ahmad Hindi by his peers while Ruhollah, a prolific writer of ghazals and other forms of poetry, would often use ‘Hindi’ as a nom de plume; this was not because they were Hindi speaking people but because they had come from Hind (the Persian name for India),” says Prof. Ahmed.

It is unclear whether Ruhollah replied to Syed Yusuf. However, within a year of establishing the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ruhollah sent Ali Khamenei, then an Imam and prominent member of the Iranian Parliament, on a visit to India. Ali Khamenei, who succeeded Ruhollah as Ayatollah and has been Iran’s Supreme Leader since 1989, made a daylong trip to Kashmir during that visit, which included a brief sermon at Srinagar’s Jama Masjid advocating brotherhood between Sunnis and Shias.

Unlike the pro-Pakistan Shah of Iran, the Iranian Republic founded by Ruhollah tilted towards India; a posture it has largely maintained since 1979 barring on occasions when it has expressed concern or outrightly condemned human rights violations in Kashmir by the Indian State, including in the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019. The Kashmir issue has, however, been a tightrope walk for the Iranian regime too.

“If you see the statements that come from the Ayatollah or the Iranian government with regard to Kashmir, the two things that are consistent are Iran’s steadfast support and solidarity for the people of Kashmir and that they almost always mention Kashmir without qualifying, like other foreign nations do, whether they are referring to Indian Kashmir or Pakistan Occupied Kashmir,” a senior Kashmiri journalist told The Federal, requesting anonymity.

The bond between Iran and Iran-e-Sagheer has withstood the test of time and even outlived the centuries-long familiarity that was deepened between the two by the Persian language, which was replaced with Urdu by the Dogras rulers in 1889. Commentaries about Kashmiris choosing the Islamic Republic of Iran to pursue higher education because of a commonality of religion are an affront to a rich and rare bonhomie that has endured the vagaries of war, the machinations of politics, the manipulations of diplomacy and even the divisions of Shia and Sunni Islam.