- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Why the SIR's launch in Bengal on filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak's birth centenary is a profound irony

For Ghatak, born on November 4, 1925, in present-day Bangladesh, all loss is metaphysical, a state of perception higher than a word like dislocation or dispossession could grasp. His works are a reminder that belonging is not just about legality and territoriality, but making a place home.

“Lost my yesterdays, when are where/ And how they were lost, the mind knows not./ Now when I sit down to ponder,/ It feels strange to calculate and wonder,/ This rhythmless scattered life of mine.” Thus begins one of Ritwik Ghatak’s untitled, unpublished poems, found among his papers and translated from Bengali by Brinda Bose. One can see it as a common lamentation that...

“Lost my yesterdays, when are where/ And how they were lost, the mind knows not./ Now when I sit down to ponder,/ It feels strange to calculate and wonder,/ This rhythmless scattered life of mine.”

Thus begins one of Ritwik Ghatak’s untitled, unpublished poems, found among his papers and translated from Bengali by Brinda Bose. One can see it as a common lamentation that inevitably disturbs any simple arithmetic of aging. But for Ghatak, any loss and all loss is metaphysical, a state of perception higher than a word like dislocation or dispossession would be able to grasp.

Born on November 4, 1925, in present-day Bangladesh, he never felt at home in the land that he had found himself in — his family migrated to West Bengal in the 1940s — and never found one in the land which became foreign (like a past) at the blink of an eye. One may want to wonder what would have happened to his cinema if the Partition of India in 1947 was for some reason to be stayed. If one knows well the work of Ghatak, one could safely say that even then, he would have been in one exile or another.

Also read: Why residents of former Bangladeshi enclaves are losing sleep over ongoing SIR in West Bengal

A state of statelessness, an existence levitating high above any normative longitude was, perhaps, as sanguinary to him as was his capacity to err on the side of rebellion. One cannot, hence, even begin to grasp the momentous irony of having the Election Commission’s (EC’s) ongoing special intensive revision (SIR) of electoral rolls reach Bengal precisely in the month when Ghatak turned hundred this November, and was being remembered with the usual kind of pageantry that accompanies such an event.

In West Bengal, the SIR is not just a question of the present, or of electoral politics, or rightwing gaslighting. Historically, Kolkata (or Calcutta as it was then known) has been accustomed to scenes of mass mobilisation and disruption. Since the early years of the twentieth century, the city has accommodated as many migrants as it has made space for oppositional movements and voices. And, in the 1940s, a strong sense of dispossession, both physical and ontological, seems to have characterised the wretched condition of much of Bengal’s middle and lower classes.

From the Bengal famine of 1943, which displaced thousands of farmers from the rural hinterland, to the violence between communities in the days leading to and following the tragic Partition of the country — which permanently de-territorialised millions of East Bengalis, forced to become refugees in West Bengal — dispossession, or more specifically an unremitting sense of un-belonging, was the tragic motif that formed both the political and cultural economy of the state.

Artistically, the disquiet of the decade had no precedent. Mass mobility, enforced by the decade in general and the Partition in particular, clearly necessitated a new poetics of mobility. There was no time for artists and critics to pontificate on technique, and yet there was no artistic precedent in traditional Bengali cultural praxis which could satisfactorily embody the scope of the massive scale of disruption.

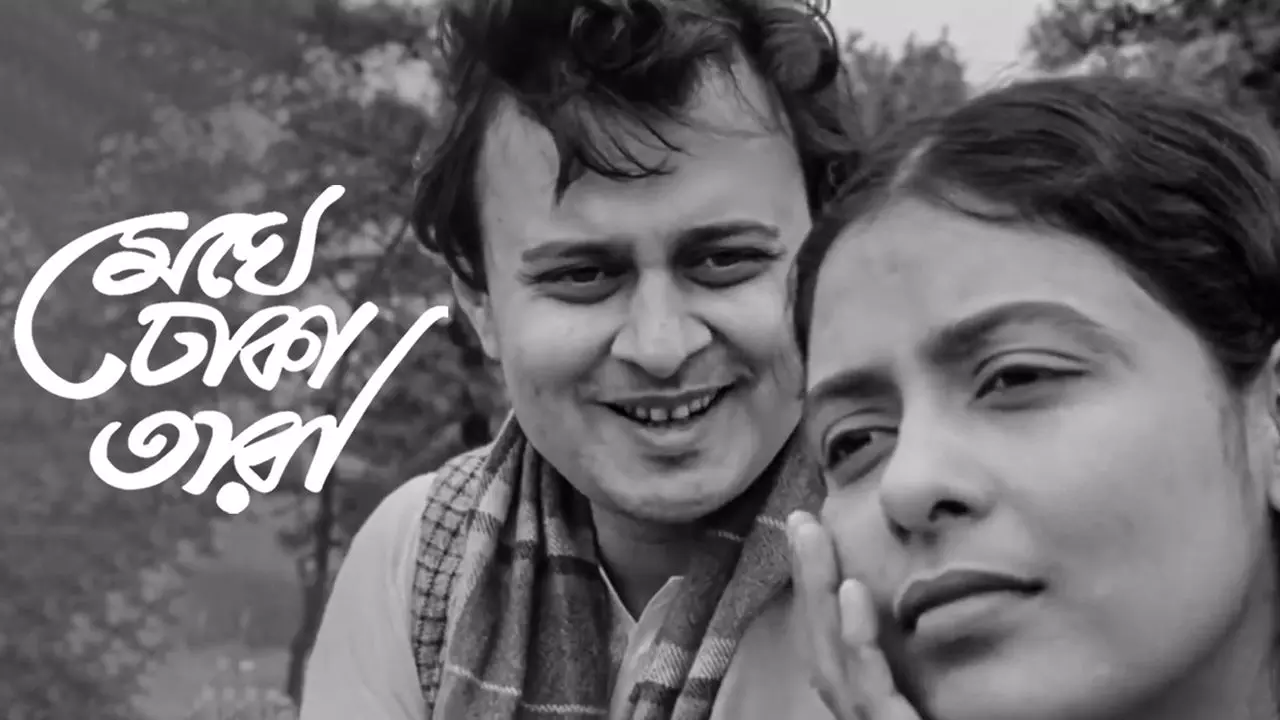

A young Ritwik Ghatak. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It was then that Ritwik Ghatak came to cinema. He did so, in terms of form and temperament, by harnessing the Indian People Theatre Association’s (IPTA’s) political angst, the formal experimentation of post-World War European art cinema and Soviet cinema’s radical aesthetics, tapping into cinema’s capacity to correspond with and respond to the present through its own language. The particular power of moving images to convert the accuracy of embattled space and time into an appropriate cinematic language was certainly not lost to him and several others.

Also read: ‘Dead’ voters walking in Bihar, hundreds deleted from rolls in villages near Patna

Ghatak saw cinema as a potent medium to bring into fruition the uncompromising, radical mission of art. In spite of his copious talent, reckless disorderliness, financial troubles and surrender to alcoholism militated against his desire for a more fulsome career in cinema. Ghatak could complete only eight full-length films, three of which — Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star, 1969), Komal Gandhar (a musical note, corresponding E-Flat of western classical music, 1961) and Subarnarekha (The Golden Thread, 1965) — deal with Partition and constitute the basis of his international fame.

Meghe Dhaka Tara is an intense, merciless exploration of the internal divisions and convictions of an average ‘Partitioned’ family; Komal Gandhar is the story of a theatre group under the embittering signifier of Partition. If Meghe Dhaka Tara tested Partition within the moral universe of a family, Komal Gandhar tested it in the context of self-imposed boundaries of social contract and conflict within a community of artists. Subarnarekha, somewhere in between, is about a family which splinters into two, one half leaving the secure shelter of the province to scratch out a hard living in the city, only to find their past tragically catching up with them. In this film too, every event is marked by the Partition.

Ghatak’s trilogy, in sum, is as much triggered by Partition as it is haunted by it, investing the Partition with the moral weight and irretrievability of the apocalypse. For him, at least for his cinema, the Partition was not a period, but a ‘geospatial’ fissure, a sequestering of both land and time that was sharply parcelled out and waylaid from any equivalence of continuity.

A scene from the Bengali film Meghe Dhaka Tara, part of Ritwik Ghatak's Partition trilogy.

Equally crucial, in intent, if not craft, was Nagarik (The Citizen), Ghatak’s first, unreleased film. Nagarik explores a middle-class family’s descent into poverty while desperately trying to hold on to bhadrolok (gentlemanly) mores. As littérateur and critic Sibaji Bandyopadhyay once wrote: ‘It is undeniable that Nagarik’s characters, like those of the trilogy, try to grapple with the problem of instantaneous switch in the substantive meaning of belonging.”

Ironically, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Yuva Morcha had reportedly released a video in 2019 in support of the controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act, which included clips from Ghatak’s Partition trilogy. The move had purportedly drawn sharp criticism from the late filmmaker’s family, who had condemned the “misappropriation and misuse of his politics and his cinema”.

Now, the SIR, which puts back the question of belonging at the heart of citizenship in India, especially in the context of Bengal's embittered history of embattled spaces, coincidentally began in the state on the very day of Ghatak’s birth centenary.

Also read: 20 years of the RTI law: How a marquee legislation has been weakened and diluted

One cannot but be alarmed by the sharp sliding of credibility that the EC has suffered in India lately, accused of providing no safeguards or defence against alleged mass-scale electoral fraud engineered by the ruling regime. According to reports, during the SIR exercise in Bihar undertaken months earlier, the commission had assured the Supreme Court that those found ineligible for electoral roll registration under SIR would not lose citizenship.

Prima facie, the SIR is an exercise undertaken by the EC to weed out fake, dead or illegal voters from any list of the EC-defined idea of ‘citizenship’. To that end, it is supposed to enjoy a certain constitutional validity.

But the question, as we know, is never simply that of legality. The question is also of ‘belonging’. Does not the SIR make the poor and the vulnerable become a playground between the contingency of electoral numbers and the sudden stringency of the election commission?

As Ghatak would remind again and again, belonging is not just a question of legality, authority, territoriality and borders but also having made a place home and hearth, of labour, and of finding the ground beneath one’s feet.