- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Samudaya at 50: Why Karnataka’s theatre collective must reinvent to stay relevant

Conceived to bring about social change in Karnataka, the Samudaya movement gained momentum during Emergency; as it confronts a democracy under new strains, it reflects on its legacy and its future relevance

The year was 1975. A movement to use theatre as a cultural expression of democratic upsurge and the yearning for radical change was quietly gathering strength in Bengaluru. Among its key figures were the now-renowned theatre personality Prasanna Heggodu and Bangalore University professors like C Veeranna, KV Narayan, Ki Ram Nagaraj and Shudra Srinivas, along with the distinguished thinker...

The year was 1975. A movement to use theatre as a cultural expression of democratic upsurge and the yearning for radical change was quietly gathering strength in Bengaluru. Among its key figures were the now-renowned theatre personality Prasanna Heggodu and Bangalore University professors like C Veeranna, KV Narayan, Ki Ram Nagaraj and Shudra Srinivas, along with the distinguished thinker and cultural critic DR Nagaraj and the Dalit poet Siddalingaiah. They named it Samudaya, a theatre collective committed to bringing about social change in Karnataka.

The movement gathered momentum with the declaration of Emergency by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi the same year. “It was Prasanna, who was then studying at the National School of Drama (NSD), who conceived the basic idea of Samudaya,” recalled CK Gundanna, former secretary of the troupe that turned 50 this year.

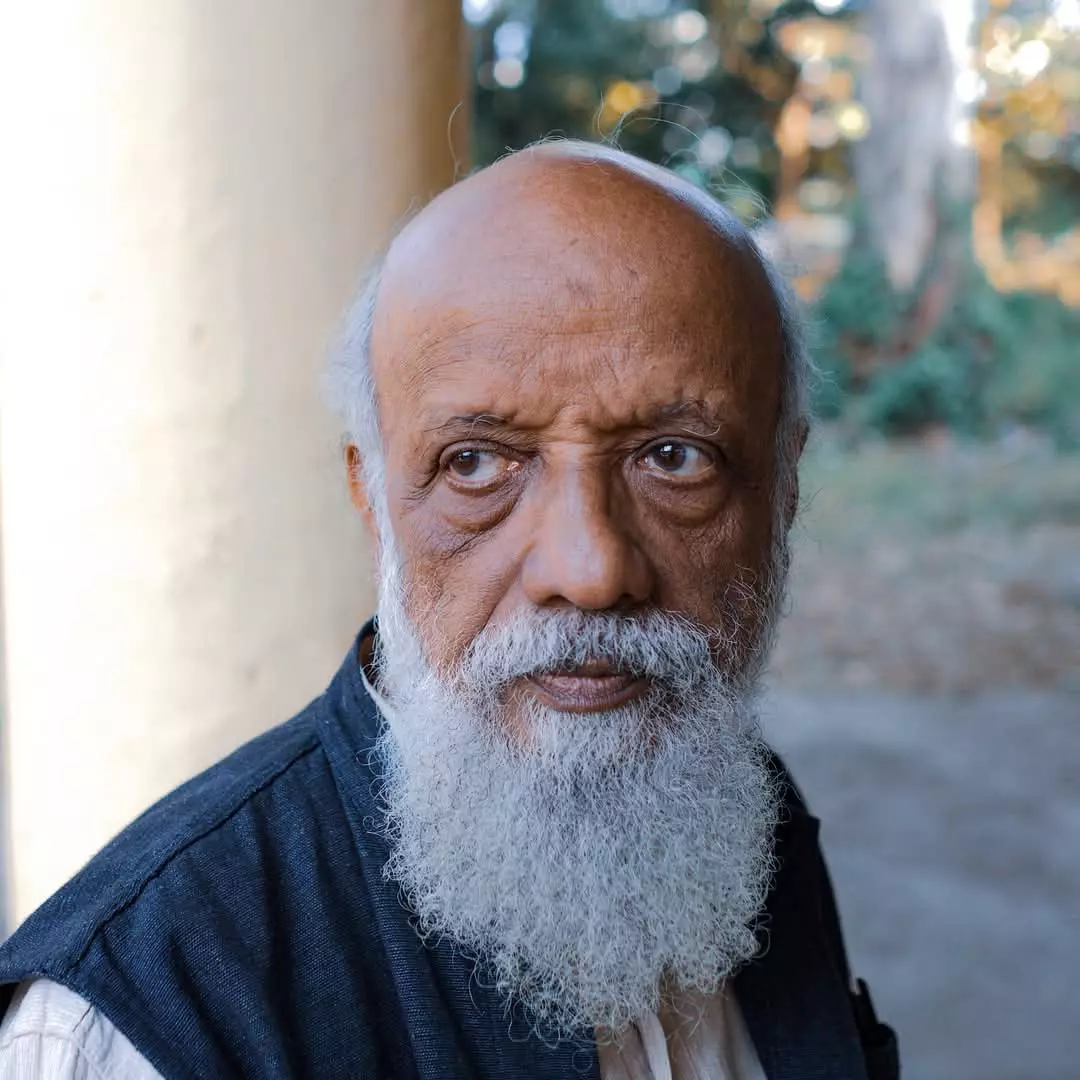

Prasanna, who conceived the idea of Samudaya while still a student at NSD as a cultural movement grounded in the philosophy of 'Art for Life'. Photo by special arrangement

Currently the convenor of Samudaya’s Golden Jubilee celebrations, Gundanna added: “His vision was to encourage a cultural movement grounded in the principle of ‘Art for Life’, as opposed to the reactionary notion of ‘Art for Art’s Sake’. He saw theatre and visual media as vehicles of social change. During holidays at NSD [when he would visit Bangalore], he shared his ideas with fellow theatre enthusiasts, cultural personalities and thus, the foundation of Samudaya was laid.”

The scope of the movement soon broadened. “Along with theatre, the idea of including cinema and circulating progressive literature took root. These efforts sought to inculcate a scientific temper, support struggles against exploitation, and uphold national sovereignty, integrity, democracy, and world peace — seen as essential preconditions for social change,” Gundanna told The Federal.

Also read: How West Bengal is teaching kids compassion for strays, ways to avoid dog bite

In Sthala Purana, an essay that forms part of the anthology Multiple City: writings on Bangalore, edited by Aditi De, photo and visual artist Pushpamala N, chronicled the early years of Samudaya. The idea was to “form a broadly Left theatre group based on the lines of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and the Kerala People’s Art Club. The name Samudaya was suggested by the cultural critic Ki Ram Nagaraj, describing the movement as ‘eternal and unfading’,” she wrote.

Pushpamala added: “In the Samudaya jatha [fair] started by Prasanna, urban youth travelled all over rural Karnataka, for the first time, putting up agit-prop street plays, while staying with locals.”

A play by the collective. Photo by special arrangement

Samudaya’s first production, Huttava Badidare (Beating the Burrow), was written by KV Narayan and directed by Prasanna. It offered a radical reinterpretation of Vigada Vikramaraya, a play by noted dramatist and novelist Swamy Venkatadri Iyer (known by his pen name Samsa), who himself suffered from persecution mania. In Huttava Badidare, a valiant king was presented through the eyes of two palace guards who observed that nothing in the system truly changed, even when kings were replaced. “It was a resounding success,” recalled Shashidhar Bharigat, a renowned theatre personality in Karnataka and one of the group’s earliest members.

As the socio-political impact of the Emergency started being felt across Karnataka, Samudaya responded with plays that directly challenged authoritarianism. “Although the repression in Karnataka was not as severe as in the northern states, democratic resistance was visible here too. Dalit and anti-caste movements, along with workers’ and peasants’ struggles, created a strong demand for social and economic transformation. In such a climate, the role of writers, artists, and their social commitment came under sharp scrutiny. Many were radicalised by these circumstances — and Samudaya was the outcome,” theatre and film personality, HS Krishnamurthy (popularly known as HaSaKru), a close associate of Prasanna and a founding member of Samudaya, told The Federal.

Also read: Why the same activists, political leaders are detained every time PM Modi visits Gujarat

By mid-1977, when the Emergency was lifted, Samudaya had grown into a vibrant statewide progressive cultural movement, recalled JC Shashidhar, current president of the collective.

One of Samudaya’s landmark initiatives was the 1978 cultural jatha, ‘Against Authoritarianism’, organised in the wake of Indira Gandhi contesting a crucial by-election from Chikkamagaluru. A wide anti-authoritarian platform was forged with other theatre and cultural groups to stage plays, street performances, and public campaigns. Plays like Turkman Gate, inspired by the brutal demolitions in Delhi during the Emergency, were staged across Chikkamagaluru. Encouraged by this success, Samudaya began conducting large-scale cultural jathas.

During its first decade, Samudaya worked both in the proscenium and in public spaces, creating significant productions. In 1979, Badal Sircar’s Shatabdi troupe staged four plays under its banner, marking a significant exchange between radical theatre movements across states. The post-Emergency years saw a surge of workers’ and peasants’ struggles. The Malaprabha peasant revolt shook the state in 1980. In response, Samudaya organised the ‘Towards Peasants’ jatha. Similar cultural campaigns were held after the Bhopal Gas Tragedy (1984) and during the severe droughts in Karnataka.

“Progressive movements in Karnataka like the Bandaya [Rebel, literary movement] and Dalit awakening and the People’s Science Movement, grew out of Samudaya,” wrote Pushpamala.

Late actor Irrfan Khan (left) with Prasanna. Photo by special arrangement

A major moment came in 1989, when the murder of street theatre activist Safdar Hashmi in Ghaziabad sparked outrage across the country. For three-and-a-half months, Samudaya units staged protest plays and performances.

The cataclysmic events of the early 1990s — the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc, the Bombay riots, the demolition of the Babri Masjid, and the rise of communal politics — however, had a profound impact on Samudaya. These posed new threats to the country’s diversified culture, secular and federal values. And Samudaya needed to reinvent itself to meet the demands of the time.

The group had already begun facing a shortage of artists and organisers by the 1980s. “Most artists who went to the NSD never returned,” claimed Bharigat. By the 1990s, ideological disorientation and declining cadre strength made survival difficult. Yet dedicated activists kept the organisation alive and provided leadership that continues to this day.

Also read: How ragi and jowar rotis, a village staple, became urban superfood in Telugu states

As Samudaya turns 50, “a volume is being planned on the movement, along with a national (or possibly international) theatre festival, district-level street play festivals, seminars, conventions, and lecture series”, said GN Mohan, a member of Samudaya’s Golden Jubilee celebration committee. “The group also plans to publish more than fifty booklets on social and cultural issues and to use digital platforms to widen its reach,” Mohan added.

A pressing question on some minds is, however, whether the collective can continue to stand against the socio-economic and political climate today, perceived at times as “authoritarian, anti-democratic, and [with] divisive tendencies”? For musicologist, theatre person, writer, and editor MK Shankar — himself once part of Samudaya and an actor in plays such as Thaayi (Kannada term for Bertolt Brecht's play, The Mother, an adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s novel about the Russian Revolution) — this is the “central challenge” facing Samudaya.

“Samudaya sharpened public awareness of a crucial denial — that of freedom of expression and a free press. Its campaigns helped spread the realisation that Indira Gandhi’s draconian measures must be resisted and that she had to be defeated electorally. And defeated she was — a reminder that despite her overreach, she had not dismantled the democratic process itself,” Shankar said. Today, however, “those very [electoral] institutions stand on shakier ground,” he claimed.

In such a context, Shankar cautioned, organisations like Samudaya could not restrict themselves to addressing broad issues of socio-economic hierarchies and inequalities alone. “They must also draw attention to the subtler but equally dangerous manipulations of electoral processes.” Acknowledging Shankar’s arguments, Prasanna agreed that Samudaya had to change to meet the contemporary democratic requirements of the society.

In his work Staging a Change published by Samudaya Publication in 1979, Narendra Pani, economist and professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS) Bengaluru, stated, “no matter how many questions Samudaya is stopped from asking, in an unjust world, there will always be many more to ask”. He was right then and remains so today.