- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How a marble monument and its immortal art are mesmerising viewers at an ongoing exhibition

The show in Delhi, of the art and photography of the Taj Mahal, is a walk through the gilded but forgotten pages of history and a visual delight that enthrals us, just as the monument has mesmerised poets, historians and travellers across centuries.

Mughal rulers left their stamp on India in the form of incredible architecture and beautiful gardens, which were really paradise imagined. Their overwhelming yearning to reach paradise by replicating it is evident here, so much so that even centuries later, viewers never tire of looking and relooking at the beauty of Humayun’s Tomb, the Agra Fort and the many mosques and gardens that dot...

Mughal rulers left their stamp on India in the form of incredible architecture and beautiful gardens, which were really paradise imagined. Their overwhelming yearning to reach paradise by replicating it is evident here, so much so that even centuries later, viewers never tire of looking and relooking at the beauty of Humayun’s Tomb, the Agra Fort and the many mosques and gardens that dot mostly Delhi and Agra. In the past 300 years, many poets, historians and painters have stood in front of these monuments, trying to understand their scale, beauty and purpose. Was it love, was it just a beautiful place to rest in eternal peace, or was it an attempt to leave behind the materialism that the empire itself revelled in and reach heaven?

Of all these monuments, however, none can surpass the beauty and immortality of the Taj Mahal.

And now, the DAG (earlier the Delhi Art Gallery), in an exhibition titled “The Mute Eloquence of the Taj Mahal: Ba-Zaban-E B-Zabani”, has brought us a huge collection of paintings and photographs, covering 300 years, that opens up a forgotten world before us. Wonderfully curated by medieval history expert and a proponent of India’s cultural heritage, Rana Safvi and on view till December, the exhibition gives us the privilege to stand before ages of great art created by travellers, calligraphers and painters, all of them sharing a universal belief — what a thing of beauty!

The passing of Shah Jahan, artist unknown. Photo by Binoo K John

Shah Jahan’s court chronicler, Abdul Hamid Lahori, spoke of the mute eloquence of what he called the ‘Rauza-i-Munawwara’, the first name for the Taj. According to Safvi, the tomb speaks to us of the beliefs, aspirations and condition of emperor Shah Jahan and his queen, Mumtaz Mahal, for whom he built this monument. The exhibition also throws light on the twin roles of the Taj as a private family monument and a public imperial one.

Also read: How GI tag has brought fresh focus to ‘Kutch Ajrakh’, helped find new platforms for promotion

What catches the eye immediately is the huge number of company paintings that have completely romanticised the Taj and what it stood for. Company painters of the Agra school (all Indians, but no name attached) painted in intricate detail, including the motifs on the monument, while other colonial or British painters preferred a romaticised view of the Taj. Two wonderful paintings by Charles William Bartlett, ‘Taj Mahal from the Desert’ and’ Taj Mahal at Sunset’ (Japanese woodblock print on paper), are stark examples. Another one, by Frederick Swinnerton, ‘View of Agra with the Taj in the background’, is also so realistic. Both paintings have camels in the foreground walking through the river bank. S. Bagchi’s oil on canvas captures the ochre sky of sunset with the Taj reflected in the river Jumna (or Yamuna). “The Gateway of the Taj”, a watercolour by Dutch painter Marius Bauer, is equally fascinating. Near the gate on the left of the painting can be seen a traveling minstrel with his impediments.

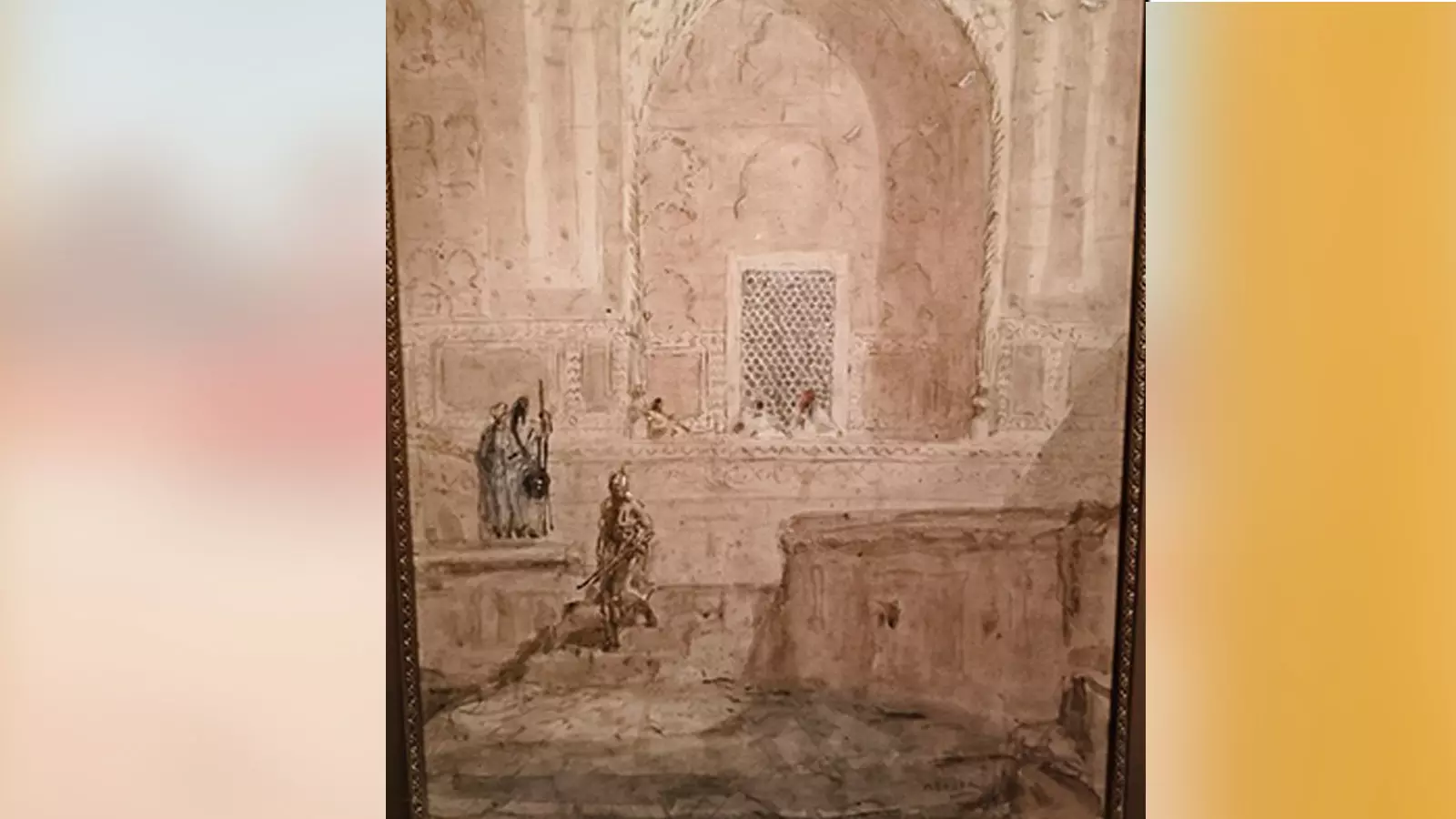

The Gateway of Taj, by Marius Bauer. Photo by Binoo K John

Perhaps the best oil on show is one by Danish artist Hugo Vilfred Pedusin, “The emperor Shah Jahan imprisoned in Agra”. Completely poignant, it shows the half-naked emperor trying to elbow himself up on his bed to talk to a regally dressed attendant and through the open window can be seen the Taj in the distance. This painting resonates with the only photograph of a Mughal emperor we have, Bahadur Shah, in his last days in Burma. But Bahadur Shah had no thing of beauty to peer at through the window.

A nude painting of Mumtaz Mahal in all her glory, painted in a red hue, is equally amazing. Her cloth cover is pulled aside to show her breasts and the magnificent jewellery that adorns her. This painting must have been done to show why Shah Jahan was completely in awe of her.

The Imprisonment of Shah Jahan, by Hugo Vilfred Pedusin. Photo by Binoo K John

Samuel Bourne, Felice Beato and other European photographers captured the Taj from various angles and most of them from the back with the river flowing. Many photographers neglected the interiors of the Taj as well as the inscriptions with inlays that adorn the marble. Bourne, however, shot the screen enclosing the sarcophagi in the basement of the Taj, which can be seen in the exhibition.

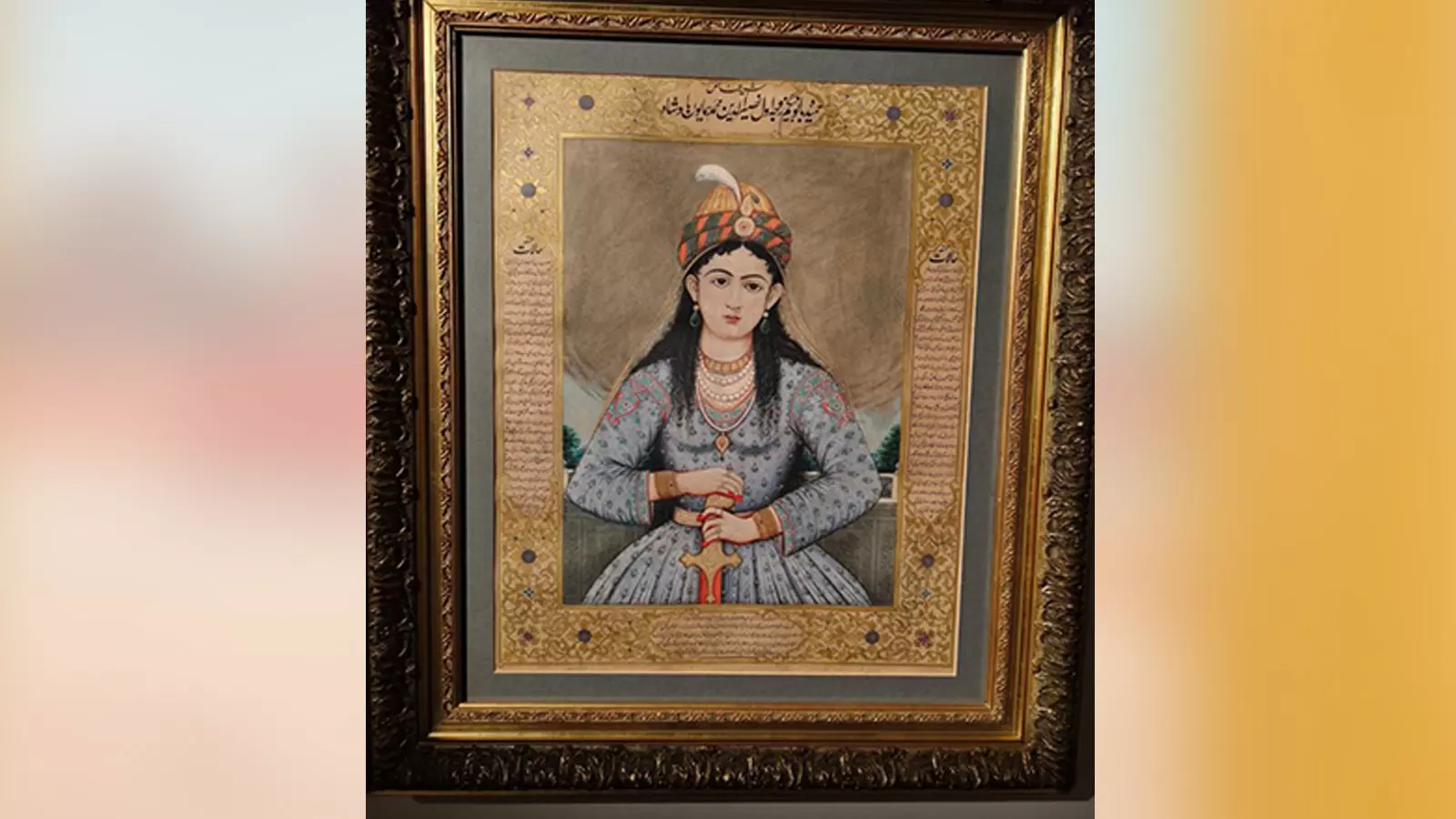

Portrait of Hamida Banu Begum, wife of Humayun, by unknown artist. Photo by Binoo K John

“Pictures of the interior of the tomb give us a more intimate view of the burial place of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan. The best and most numerous works of this kind are by Company artists from the early 19th century. They developed an ambitious depiction of the whole height of the interior. Though this view was often repeated, they focused more usually on details of the pietra dura inlay, the coloured ornament on the cenotaphs, and the surrounding screen…the photographers followed suit,” writes Safvi.

In many photographs of the 20th century, the Taj is a monument raising its head in the background, while people went about their lives in the foreground. This is especially visible in the photos of Raghu Rai (not a part of this exhibition), who reinterpreted the Taj in a book of photographs of the monument. The area around the Taj or Taj Gunj finds play in paintings, but photographers largely avoided it, inexorably attracted towards the marble monument. The tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulah in the complex — built by Nur Jahan, wife of emperor Jahangir, for her father Mirzā Ghiyās Beg, who had been awarded the title I'timād-ud-Daulah, meaning pillar of the state — popularly referred to as the ‘baby Taj’, can also be seen in many of the paintings on display, just like the Agra Fort on the bend in the river.

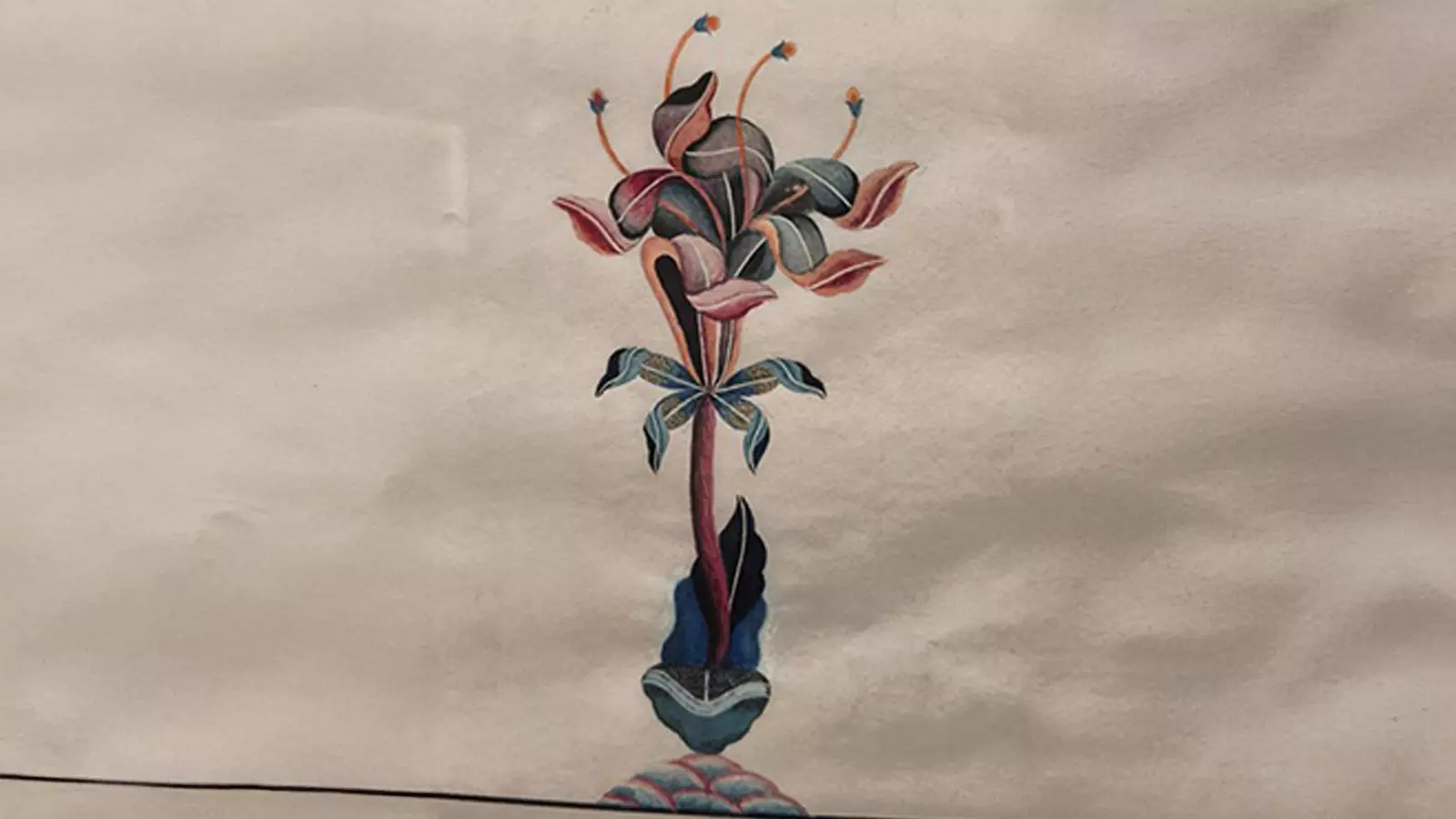

Agra Artist Company painting, Details of Shah Jahan's Tomb. Photo by Binoo K John

Also read: A prized possession for generations, why Mysore silk sarees are failing to keep up with demand

The exhibition is an experience in itself. Whether as a walk through history or admiration of the sheer creation of beauty on view, all the paintings seem to prove what Shah Jahan’s court poet Kalim wrote in 1643 on the 12th anniversary of Mumtaz's death:

“Since heaven’s vault has been standing , an edifice like this

Has never risen to compete against the sky

IN colour resembles dawn’s bright face,

For both inside and out, it is entirely marble,

No, not marble, for in respect of delicacy and beauty

The eye can mistake it for a cloud.”