- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

The scars of a Gorkha rebellion in the Himalayan foothills

A few decades back, it was a common sight in many Indian towns during midnight to see Gorkhas patrolling on bicycles, striking cane sticks against the road and blowing whistles. The men, dressed in khaki (though some favoured dark green), carried a whistle, a torch, and a lathi. They concealed a secret weapon within the lower pockets of their shirts: the kukri, a knife characterised by its...

A few decades back, it was a common sight in many Indian towns during midnight to see Gorkhas patrolling on bicycles, striking cane sticks against the road and blowing whistles. The men, dressed in khaki (though some favoured dark green), carried a whistle, a torch, and a lathi. They concealed a secret weapon within the lower pockets of their shirts: the kukri, a knife characterised by its unique recurve, which serves as a traditional symbol of identity for the Gorkhas.

It was widely believed that the kukri must draw blood before it can be sheathed. The Gorkhas appeared composed and serene, and the presence of the kukri instilled in them a sense of bravery and identity. The Gorkhas gained immense popularity, with several individuals quickly becoming celebrated figures in literature and film. In 1986, the renowned actor Mohanlal brought to life the character of a Gorkha named Ram Singh in the Malayalam film Gandhinagar 2nd Steet. This film was subsequently adapted into Telugu as Gandhinagar Rendava Veedhi and into Tamil as Annanagar Mudhal Theru.

Who are these Gorkhas? The term ‘Gorkha’ originates from a small town, which is now a district, in Nepal that shares the same name. Situated 40 miles from Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal, the Gorkha kingdom was founded by Drabya Shah in 1559. Scholars suggest that the terms ‘Gorkha’ and ‘Nepali’ are often used interchangeably in India, although various political movements at different periods have preferred the term Gorkha to distinguish between the citizens of Nepal and those of India.

The Gorkhas, who have governed in Nepal for more than four centuries, were relatively obscure until the unification of Nepal by Prithivinarayan Shah, the 11th monarch of the Gorkha kingdom, as noted by Tanka B Subba, a scholar and author of Ethnicity, State and Development: A Case Study of the Gorkhaland Movement in Darjeeling. It is believed that the Gorkhas are of Rajput lineage and were expelled from Rajputana during an invasion by the Muslims. They initially settled near Palpa after traversing the Kumaon hills and gradually expanded their influence over Gorkha. Following the demise of Prithivinarayan in 1775, several kings emerged, but it was Girvan Juddahbikram Shah who altered the course of Gorkha history by initiating a conflict with the East India Company in 1814.

“The formidable power of this company was subdued by a lesser and poorly equipped Gorkha contingent. It was not until General Octerlony assumed command in 1815 and acquired sufficient expertise in mountain warfare that they were able to defeat the Gorkhas,” writes Tanka B Subba.

A treaty was established between the British East India Company and Nepal after the conflict. Subsequently, Darjeeling in the Himalayan foothills was developed into a tea cultivation area. The British required labour for the tea estates, which led to an open invitation for people from Nepal to migrate and work in the tea plantations. They established their homes in different regions of that area. Some chose to settle in Darjeeling, while others made their homes in Kalimpong. A significant number also migrated to Sikkim. This trend continued until 1900.

The border was not a significant barrier for them, and people frequently travelled back and forth without any substantial restrictions on movement. However, a pivotal change occurred from the early 1900s, when a sentiment emerged among the Indian Nepalese who had established themselves here, suggesting the need for a distinct state for the community. Nevertheless, the concept of a separate state for the Nepalese-speaking population in India has existed since at least the 1900s. After India’s independence, the Darjeeling region was designated as a district within the West Bengal province, where it was subsequently incorporated.

The apprehension that individuals who speak Nepali may become a minority within a larger state has been exacerbated. West Bengal, as a considerably larger state, has both a linguistic and cultural majority, while those who speak Nepali find themselves in a position of linguistic minority. This concern has always been present, and it was further emphasised by national leaders during the independence era. The worry has been that they could eventually be perceived as foreigners in India. This feeling is a fundamental aspect of the Gorkha movement, which aims to confront the fear of being seen as outsiders in their own nation.

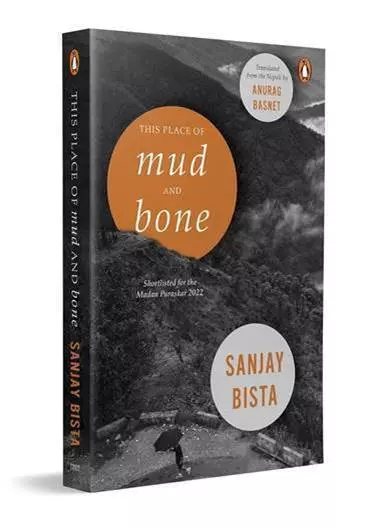

This ongoing situation underscores the historical context of the Gorkhas in India and the enduring anxiety regarding their status as potential foreigners in their homeland, which is a central theme in Sanjay Bista’s recently published book, The Place of Mud and Bone, an English translation of his Nepali novel Matako Ghar, which was shortlisted for the Madan Puraskar (Nepal’s foremost literary award) upon its release in 2022. In his novel, Bista delves into the identity crisis faced by the Nepali-speaking population in the Darjeeling hills, highlighting the idea that these individuals have frequently been categorised as migrants who settled in the Himalayan foothills of Darjeeling and Kalimpong, both of which are districts and Kurseong, which is a town and municipality with in the Darjeeling district.

The Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF) gained momentum in the 1980s due to its pursuit of a distinct state known as Gorkhaland, which was to be formed from the Darjeeling district of West Bengal. Led by Subhash Ghisingh, the GNLF initiated a movement characterised by intense and at times violent demonstrations advocating for the establishment of this state. The movement reached its zenith between 1985 and 1986, resulting in the creation of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) in 1988. But that didn’t solve the problems of the Nepali-speaking people in the Darjeeling hill region.

In 1986, Bista was just 18 years old when he observed two andolans (rebellions) occurring in Labda, a village located near Darjeeling, advocating for a separate state. Six friends ― Karnabahadur, Tshering, Ambar, Buddha, Rajvir, and Sarita attended school together in this village. The winds of andolan swept through Labda, turning the village into a battleground. Students turned against their teachers, families and villagers became divided along political lines, and everyone was compelled to take a stance. After three decades, Bista follows the lives of these schoolmates in the process of a political struggle.

This Place of Mud and Bone narrates the transformation of Karnabahadur into Angulimaal and the circumstances that compelled Buddha to take his life; it explores the reasons behind Tshering’s evolution into Tshering the murderer and ultimately Mad Tshering; it examines Ambar’s decision to end his own life; and it reveals how Sarita found herself selling eggs in a hospital.

The andolan, occurring in two distinct phases from 1986 to 1988 and again from 2007 to 2017, serves as the backdrop for the novel. “The primary motivation for the andolan stems from the anxiety of existing as a linguistic and socio-cultural minority within a predominantly larger state. The aspiration of the Nepali-speaking minority for a separate state within the Indian union can be traced back to at least the early 20th century. Over the decades, this demand has manifested in various forms and iterations, influenced by different political parties and leaders. The andolan took on a violent character in 1986 and has persisted since then,” said Bista, a faculty member at Kalimpong College in West Bengal.

Art plays a significant role in providing context for any political struggle, he said. If this is true, then why was there no artistic engagement during the struggles of the Nepali-speaking Gorkhas in the Darjeeling hills? “The urgency of events and the reactive nature of how situations unfold on the ground often restrict the time and space needed to synthesise and express these events. In the first phase of the andolan in 1986, I believe that the involvement of writers and artists as participants in it circumscribed their artistic space. Violence and political turmoil inevitably lead to migration. We have encountered, and continue to face, significant migration from our towns and villages. Continuous movement and displacement are not conducive to reflection. Nevertheless, the most crucial factor in both phases of the movement that hindered art from fulfilling its roles of documentation and analysis was the establishment of a system controlled by a single party. This has effectively silenced, and continues to silence, many voices,” he added.

As both a witness and a participant in the andolans of Darjeeling, Bista aimed to document these significant events. “Matako Ghar, which is the original title of the novel in Nepali, narrates the lived experiences of the Darjeeling hills over a span of three decades. I composed it to ensure that these events would not remain solely as oral narratives but would be accessible to contemporary and future readers in Nepali. Concurrently, I approached this task with the goal of creating art, emphasising both originality and style. The translation of this novel into English will allow our story to reach a much wider audience,” he said, clarifying the motivation behind his book, which is published by Vintage, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

This Place of Mud and Bone is the third novel based on the andolan, following Fruits of the Barren Tree by Lekhnath Chhetri and Song of the Soil by Chuden Kabimo, to be published in India. All three novels have been released after an extended period of drought and strive to comprehend a series of violent events that impacted an entire region over several decades. “These novels are not only essential for understanding what transpired, but they are also crucial for documenting that which is slowly fading from collective memory. Works like This Place of Mud and Bone are relevant. Should these three novels signify the beginning of a new wave, and should many more follow, they will all be pertinent and welcomed,” said Anurag Basnet, who translated Matako Ghar into English.

Anurag said Matako Ghar adheres to a non-linear structure, featuring an unreliable narrator who is both gossipy and insistent on exploring events from various perspectives, occasionally utilising a Rashomon technique (a term derived from Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film Rashomon, in which a crime is described in four contradictory manners by different witnesses). “In several instances, the author himself feels the need to intervene in the narrative. This all contributes to a vibrant narrative that is challenging to confine within the limits of the novel,” he added.

The Gorkhaland movement, like many other ethnic movements in Asia and Africa, was born out of colonial and neo-colonial rule, according to Tanka B Subba. “The Gorkhas or Nepalis were first subjects of the British and later of the Bengalis. For decades, they had experienced political voicelessness, cultural insecurity and economic deprivation… They were often taunted, evicted, humiliated by their neighbouring communities,” he writes. “There never was any attempt by the government to allow them to grow self-reliant, confident and at par with others. They were made accustomed to a dependency culture that never seemed to go.”