- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

The unique Gods of religion-neutral Kerala temples

It’s a 100-minute drive from Kannur, cutting inland from the coast through winding roads and rising terrain into the hilly interior of northern Kerala. The road rises and dips, cutting through small towns like Pappinisseri, Peringome, and cashew plantations, until it reaches Cherupuzha. In the foothills of the Western Ghats, the town appears unhurried, somewhat unfazed by the preoccupations...

It’s a 100-minute drive from Kannur, cutting inland from the coast through winding roads and rising terrain into the hilly interior of northern Kerala. The road rises and dips, cutting through small towns like Pappinisseri, Peringome, and cashew plantations, until it reaches Cherupuzha. In the foothills of the Western Ghats, the town appears unhurried, somewhat unfazed by the preoccupations of Kerala’s buzzing politics or religious faultlines.

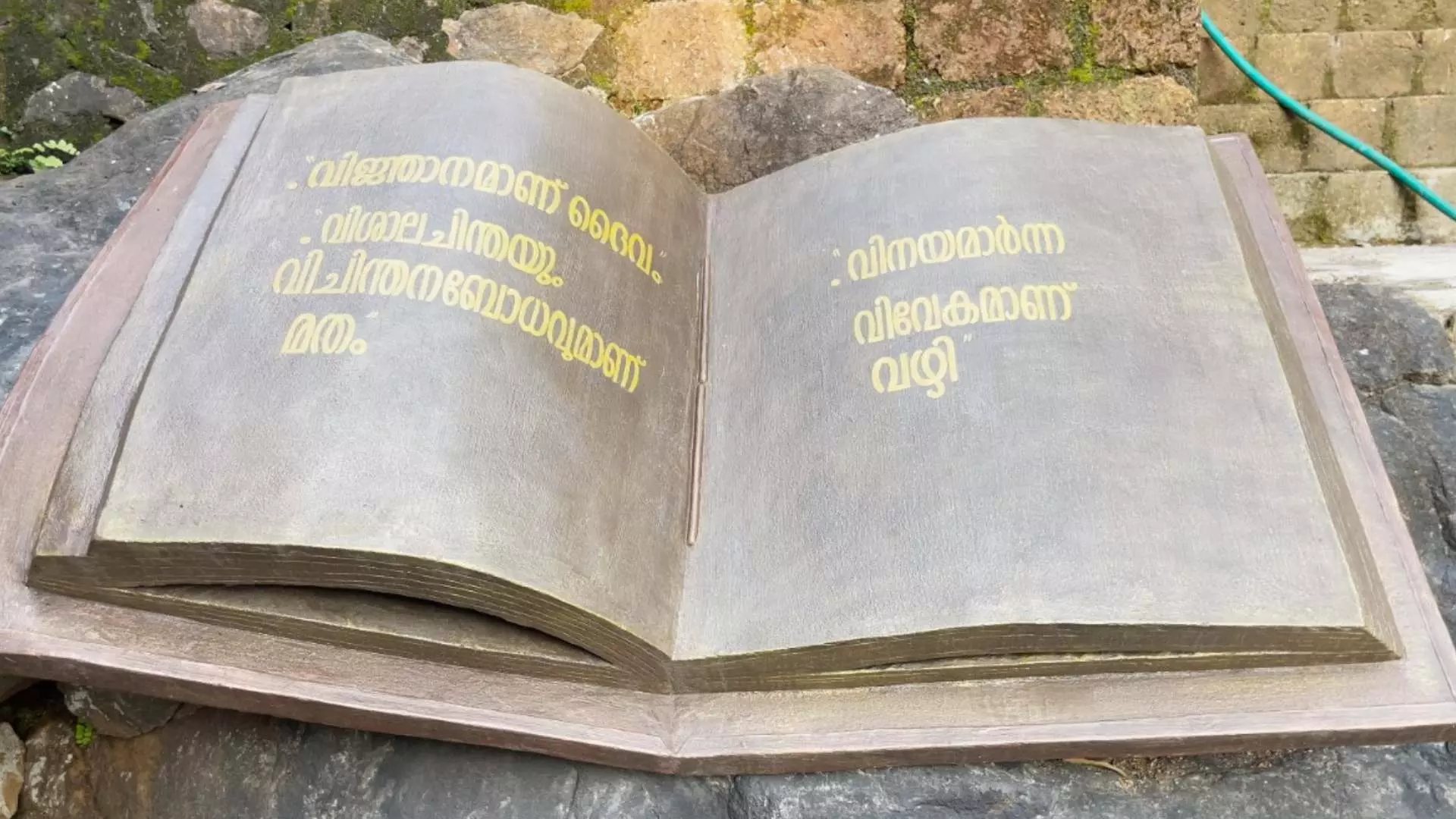

About five kilometres ahead lies Navapuram, home to the Mathatheetha Devalayam—literally, ‘the temple beyond religion’. Here, traditional markers of worship are absent: no gopuram, no temple bells, no priests in saffron or white. Instead, a towering concrete book—a ‘tome deity’—is mounted on a 30-foot stone monolith. At its base are inscribed the words: “God is knowledge. Religion is broad thinking. Humble wisdom is the path.” These aren’t mere mottos—they are the very embodiment of the deity.

Knowledge over blind worship

The temple, nestled in a neighbourhood named after 15th-century Malayalam poet Cherusseri, was not the vision of a spiritual leader or political reformer, but of Prapoil Narayanan—a writer, teacher, and the very author of the words inscribed at its base. Born in Cherupuzha, Narayanan lost his father at the age of nine and was raised by his mother. Early encounters with literature sparked in him a conviction that would shape the rest of his life: that books were sacred, and that knowledge could—and should—replace blind worship. By the time he was 16, Narayanan had begun imagining a temple that honoured this belief. It would take decades before he could make it real.

Also read | Man gets life imprisonment for brutally murdering family

“It was the influence of poet Vishnu Narayanan Namboothiri, who was my English teacher at Brennen College, Thalassery, during my pre-degree years, that led me into the world of words. The thrill of meeting a poet in person was overwhelming, and he encouraged me greatly. I too started writing, and he would correct the mistakes in my work—this is how I found my way into the world of words,” Prapoil Narayanan says recalling his formative days.

An idol of Malayalam poet Cherusseri in the temple

“Each book felt like a new pasture to explore. As I ventured into them, I could almost hear them saying, 'You're an idiot.' Every page was a vast territory waiting to be discovered, a realm of knowledge I hadn't yet encountered. In an era without TV or mobile phones, books were my sole doorway to knowledge. It was through this experience that I came to believe knowledge itself is divine. That’s when the idea of making a book the deity, instead of a traditional God, began to take shape in my mind,” he adds.

“After completing the lab technician course, I began offering tuition to local students. What started as a small tuition service eventually grew into a tuition centre, and later, a parallel college. Along with my students, I enrolled in the liberalized graduation programme of Calicut University, and that became both my profession and my identity—the parallel college.”

Also read | Tamil epic heroine Kannagi’s idol portion missing for 50 years

Throughout this journey, Narayanan was nurturing the dream of creating a secular house of worship centered around books, not just a library. He had initially started a local art and cultural society, which eventually evolved into his vision. He poured all his savings, approximately Rs 60 lakh, into the project, along with the two acres of land he owned.

There is no ‘darshan’ in the conventional sense at the temple. People come not to fold their hands in submission, but to read. Or to write. Or to simply sit among books and think.

The Mathatheetha Devalayam, designed by Narayana himself, opened its doors to the public in March 2021. The towering granite sculpture of the ‘tome deity’ was completed that October. Both the tome and the sculpture of Cherusseri were crafted by sculptor Santhosh Manasam, while other artworks — models, Gnanamayi, Buddha, Ezhuthachan etc — at the site were created by artist Shibu Vettom. The structure is striking in its restraint. Built without religious symbols, it asserts nothing but its own presence. The path to the book is lined with smaller sculptures extolling learning. An adjoining hall, filled with shelves of books donated by visitors, functions as both temple and library.

Here, there is no ‘darshan’ in the conventional sense. People come not to fold their hands in submission, but to read. Or to write. Or to simply sit among books and think.

“I visited the place with some students after hearing about it from friends. The atmosphere was incredibly captivating. The idea of this kind of dedication, especially centered around books and knowledge, was truly inspiring. Although I am a believer in Islam, it doesn't prevent me from appreciating the people behind this noble initiative, especially Narayanan Master, whom I don’t even know in person,” says KM Safeera, a higher secondary teacher from Malappuram district, who visited Navapuram in 2024.

Offerings of books

In traditional Hindu temples, offerings range from oil lamps to coconuts, incense sticks to elaborate poojas. At the Mathatheetha Devalayam, the only offering accepted is a book. Visitors bring volumes—novels, essays, poetry, non-fiction, textbooks—and place them reverently on the shelves. A catalogue is maintained, but not for ownership. The book becomes part of the temple, part of the god. This act is not metaphorical. The book is the god. There is no other idol.

"Authors often donate books to us, sometimes in large quantities, allowing us to distribute them as prasad. However, this depends on availability," says Narayanan.

Also read | China's 'renaming' of places in Arunachal leaves India combating along 2 borders

Narayanan insists what matters is not what is written in the book, but the very act of reading and writing as a sacred exchange. “When we read,” he says, “we are in conversation with generations. The book connects us to those who lived before, and those who will live after. What is more divine than that?”

Over the last three years, more than 10,000 books have been donated to the temple. The library is open all day, and rarely empty. Schoolchildren come here to study. Retired men drop in with newspapers. A cluster of young women gather around a Malayalam novel in the afternoon heat, whispering and laughing. It is quiet, but never lifeless. People from all over the country pay visits to the unique house of worship.

The idea of a temple that is not religious may seem contradictory. But in Kerala—a state both deeply spiritual and intellectually restless—it makes a certain kind of sense.

The book deity

“Initially, there was a misconception that this was against religion. For us, every religion represents the knowledge of a particular historical period and also a path to truth. Many religions began as rebellions against the conservatism of their time. While there may be distortions as they grow, ultimately, they are rectified from within. We are not against any religion. And more importantly, we do not believe that we are the only ones who are right,” says Narayanan.

Narayanan deliberately calls it a devalayam (abode of God) rather than a library or centre. “This is not just a place for reading. This is a sacred space. We have simply replaced superstition with thought. Most of our visitors are word worshipers, students, teachers and obviously writers,” he says.

Also read | Govt okays Rs 3,706-cr HCL-Foxconn semiconductor plant at Jewar

There are no priests here, and no one to enforce silence. People talk. Sometimes they argue. Every April, during the traditional school break for summer holidays, the temple organises a week long gathering, the festival.

Celebrating learning

During Vidyarambham, many children and their parents visit the temple to mark an auspicious beginning to the child’s education. Even beyond the festival, people often come here to symbolically start their child’s learning journey. The children are free to write whatever they wish—there are no constraints or rituals to follow.

The recent annual festival featured performances by the folk band Atheena, artists such as Baul singer Santhipriya, Bharatanatyam and Mohiniyattam recitals, and a seminar on Theyyam – a folkloric art – as narrated in Malayalam literature. No one comes to seek blessings. Instead, they come to share stories, ideas, and, occasionally, food. The result is a celebration not of ritual but of thought.

“I had always wished to visit that place someday and dedicate my first novel there. But the opportunity never came. It was during this year’s grand festival at Navapuram—where dance, literature, and music converge—that I got invited to the literary camp being held there. I was filled with joy. I had the chance to meet many writers I had never met before, understand the ideas of Narayanan Master, listen to enlightening talks, and speak on stage,” KV Reena a Kannur-based teacher and poet wrote on her social media handle.

“The sculptures carved into the rock crevices atop the hill, the sacred books radiating serenity within the temple, and the hosts who warmly welcomed every visitor—all of it deeply moved me. This gathering filled me with immense peace and calm,” added Reena.

The Mathatheetha Devalayam is physically small—spread across just two acres of reclaimed land—but its aspirations are wide. Two modest ‘Ezuthupura’ cottages, intended for writers and artists to work in peace, lie at one end. There is no rent. Guests are encouraged to contribute a book or a lecture instead. The place draws writers, teachers, students, and curious passersby from across the state. Some stay for hours. Others come regularly, treating the temple as an extension of their personal study space.

Importantly, there are no religious qualifications for entry. There is no need to remove footwear. No restriction on gender, caste, or religion. A devout Hindu might sit beside an atheist discussing the works of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, MT Vasudevan Nair or even Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

This radical openness is not a marketing strategy. It is the core of the temple’s philosophy: that knowledge belongs to no single tradition, and reverence for the book cannot be fenced in by faith.

Narayanan cuts an unassuming figure—soft-spoken, lean, and usually seen with a satchel of books slung over his shoulder, he looks more like a schoolteacher than the founder of a temple.

He lives nearby with his wife, Shyla, who is both his partner in running their parallel college and helps maintain the space, occasionally cooking for visitors as well. Their daughters, Nimna 29, a teacher, and Neeraja 23, both of whom have babies, also pitch in whenever they can.

"The idea was with my family even before I was born. As kids, both of us grew up with this idea and its eventual execution. We believe in what our father believed. Now, as a family—my sister, mom, grandma, and our husbands—we are all actively involved in the activities. It could be anything from cooking for the guests and handling chores to participating in discussions, especially as a literature student and teacher," says Nimna Narayanan, the elder daughter of Prapoil Narayanan.

It was important to Narayanan that the temple not bear his name. Though the land belonged to him and the structure was built using his savings and income from a tuition centre and small-scale farming on his property, he chose to keep himself in the background. Sabu Maliyekkal, Narayanan’s friend, stands by him in organising the festival and other activities, effectively serving as the de facto secretary of the temple.

Grants and donations

No political backing, no sponsors. Today, the temple operates without government grants or corporate donations. Maintenance is handled by Narayanan and family.

“No donation is truly a donation if it is asked for. I believe donations should come from the donor's will. As of now, this is a private institution, but we have plans to establish a trust. Many people, including the local government, are considering ways to help us. A couple of months ago, CPI(M) leader MV Jayarajan paid a visit to us," said Narayanan.

A secular house of worship centered around books

Workshops are held every few months—on creative writing, filmmaking, translation, folk traditions, and even financial literacy. The focus is not on certificate-giving but skill-sharing.

In an age of social media and algorithmic echo chambers, the temple offers something slower, quieter, and more deliberate: time to think. The idea of a secular, book-worshipping temple might seem like a novelty. But in Kerala, where literacy is often worn like a badge of honour, it also feels like a natural next step. The Mathatheetha Devalayam challenges not only religious orthodoxy, but also intellectual elitism. It says: the book is sacred, but it is not exclusive. It belongs in the hands of everyone. In doing so, it revives a question that often lies buried under rituals and doctrines: What does it mean to be spiritual in our times? For Narayanan, the answer is clear. “To think freely. To learn continuously. To respect the intelligence of others.” That, he says, is worship.