- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Used and forgotten: The untold stories of Dalits of 2002 Gujarat riots

Sejal ben’s day starts at 5 am with usual household chores. She then leaves for work. For the last 20 years, Sejal ben has worked as a manual scavenger around the villages in Ahmedabad district to earn a livelihood and raise her daughter.Forty-one-year-old Sejal is the wife of Dulat Parmar, one of the accused in 2002 Gulberg Society riots case. Her world fell apart in June 2016 when...

Sejal ben’s day starts at 5 am with usual household chores. She then leaves for work. For the last 20 years, Sejal ben has worked as a manual scavenger around the villages in Ahmedabad district to earn a livelihood and raise her daughter.

Forty-one-year-old Sejal is the wife of Dulat Parmar, one of the accused in 2002 Gulberg Society riots case. Her world fell apart in June 2016 when the Metropolitan Court in Ahmedabad found Parmar and 23 others guilty of murdering 69 Muslims including former Congress MP Ehsan Jafri in Gulberg Society, an upper-middle class gated society in Naroda area of the city.

Amongst the accused were VHP leader Jaideep Patel, former BJP corporator Vallabhbhai Patel, Bajrang Dal leader Rajubhai Patel, along with 19 others out of whom 6 belong to Patel community and the other 16 were Dalit men.

The plight of Dalit families

“When he got jailed in 2016, I had hope that the leaders will help us. After all, my husband was told he is an important member of the Hindu movement. But years passed and he remained in jail. I had to raise my daughter alone with no financial support from anyone. Manual scavenging fetched me around Rs 100 a day as people usually pay less to women. The VHP leaders wouldn’t even meet me. The only person who was accessible was Hitesh bhai (former BJP corporator). He kept assuring me that leaders have not forgotten him (Dulat) and his ‘sacrifice’,” Sejal ben tells The Federal.

In December 2019, the Gujarat High Court acquitted 10 accused of Gulberg Society massacre case on ground of lack of evidence while upholding life sentence of 16 Dalit men on grounds that they were ‘positively identified’ by the victims. In April 2025, the Supreme Court upheld the High Court’s verdict.

Amongst those acquitted were Jaideep Patel, Valabh bhai Patel, Raju bhai Patel and six other Patel men who had been out on bail.

“It was the darkest day of my life. I lost all hope. For years, I have battled financial crisis, social boycott and threats in the hope that one day it will all be fine when Dulat comes home to us. But I feel lost now. They (public prosecutor) told me the case is closed and nothing can be done,” shares Sejal as she breaks down.

“We used to live in Sardarpura area (in East Ahmedabad). We did not have much but we were happy. Shalu, our daughter, was around four years old. I was pregnant with my second child. Dulat used to work in a chemical factory in the city. Money was enough for us sustain. But then he began to attend meetings. Leaders would come and call him and tell him how he had a responsibility as a Hindu to stand up against Muslims,” she says.

“At first I told him not to go. But he was promised house and land that Muslims would vacate. And then one day in February 2002, he left saying he is going to attend a meeting and did not come back for a week. When he came back home finally, he had changed… in fact everything had changed. He was arrested in August 2002 and we had to shift out of Sardarpura. We couldn’t live there anymore. Incidents of violence followed many months after the riots. Muslims and Dalits would kill each other for revenge. I left the day I was threatened with rape. The next week, I had a miscarriage,” she adds.

Sejal now lives in Vejalpur area of western Ahmedabad where around 60 other Dalit families live in a slum flanked by affluent societies. But the 60 huts of the slum have no access to water, sanitation, electricity or any other civic facility. In fact, the homes have been destroyed by local authorities as illegal encroachment several times already and they face a constant threat of eviction.

“In the years, I have lived in many slums across Ahmedabad but have never been accepted by the other residents. Everyone called us murderers and wished my husband was given death sentence. Finally, in 2023, I shifted here in this slum where there are two more families like us whose men are accused of rioting,” tells Sejal.

There are many women who face the same fate as Sejal and bear the brunt of being the family of men accused or convicted of rioting and killing people.

In 2011, a special fast-track court in Mehsana had sentenced 31 people found guilty of killing and burning 39 Muslims to death and raping and murder of three women. All 31 were awarded life sentence, a fine of Rs 20,000 each. Six months of rigorous imprisonment were added for the accused who couldn’t pay the fine.

This was the first verdict in the 2002 Gujarat riots cases. All accused were charged with murder, attempt to murder, arson, rioting and criminal conspiracy.

By 2021, all accused belonging to Patel community including a local BJP leader were acquitted except for three men who belonged to Valmiki, a sub community amongst the Dalits.

The then additional sessions judge, LG Chudasma, while acquitting the 28 men held that the prosecution case was based on “mere suspicion without any evidence on record”.

“There were two parts of the case – one was murder of 39 Muslims, including seven children and the other was rape and murder of three Muslims women. In total 112 witnesses gave their testimony against the accused and identified them. Each witness told their own story of what they endured on the day and singled out the accused who killed their family members. But not one testimony was granted in the first case stating that it was merely the suspicion of the victims who cannot be certain that they saw the same men (accused). Ironically, testimonies of the same victims were admitted in the second case where accused were three dalit men,” says advocate Sohail Tirmizi who represented the victims.

“We are not happy with the verdict and have been preparing to challenge it in the apex court,” he added.

Left like they never existed

Reba Valmiki (name changed) is the wife of one of the Dalit men found guilty in the Mehsana case.

“I never wanted my husband to join these groups. I tried to stop him many times. But did not listen to me. Now, we are bearing the brunt of his actions,” says 57-year-old Reba who has been the sole earner of the family of three since her husband was jailed.

Since 2011, Rita has done everything to earn a livelihood and feed her two children – a son and two daughters who are now 22, 26 and 27 respectively.

“Just after the riots, we were moving around from one area to the other as no Dalit locality would have us. They feared that if we come to stay with them Muslims might retaliate and attack them as well. During those days many such incidents used to happen often. There were incidents of communal attack by both groups. We could only settle down in a slum of Valmikis (a sub caste of Dalits considered lowest in hierarchy) in 2013. Initially nobody would hire me in any job even as a manual scavenger. So, I began to brew country liquor in my house. However, the money wasn’t enough and there was a constant risk of being arrested. In 2017, one of my buyers asked me if I would like to get into a drug trial with promises of a good money. I readily agreed. Since then I have been part of four different drug trials that caused several illness. But I had to do it to feed my children,” shares 47-year-old Valmiki, who looks frail and older than her age.

“I am currently struggling to get my daughter married. But no one wants to marry the daughter of a riot accused. My son is also struggling to find work. He has studied till class eight. It has been more than 20 years, yet we have not been able to live a normal life. My husband’s actions still haunts us,” she shares.

“The Muslims were exposed to horrific the violence in the 2002 riots but the next biggest casualty were the Dalits. Out of more than 1,200 killed (officially) more than 100 were Dalits. These young Dalit men were misguided by the Right-wing leaders and now when all big leaders are acquitted, the Dalits are in jail. Now no one takes care of the families of the many Dalits who were arrested for the riots or those who died. The women of these families bore the brunt of the situation. Many women have been pushed into illegal activities like brewing country liquor and prostitution and some even opted to be guinea pigs for drug trials for the sake of money,” says Martin Macwan, who heads the Dalit rights NGO Navsarjan.

“Even the Right-wing organisations were hesitant for many years in helping the families of riots accused and convicted. Up until 2016, Dalits were pushed to a corner and largely remained invisible for political parties as well. It was only when the Una flogging incident happened, the issue of Dalit rights came to be included in political discourse. The incident brought back the issue of Dalit-Muslim unity with upper caste Hindus as common enemies,” Macwan tells The Federal.

The riot’s face effaced

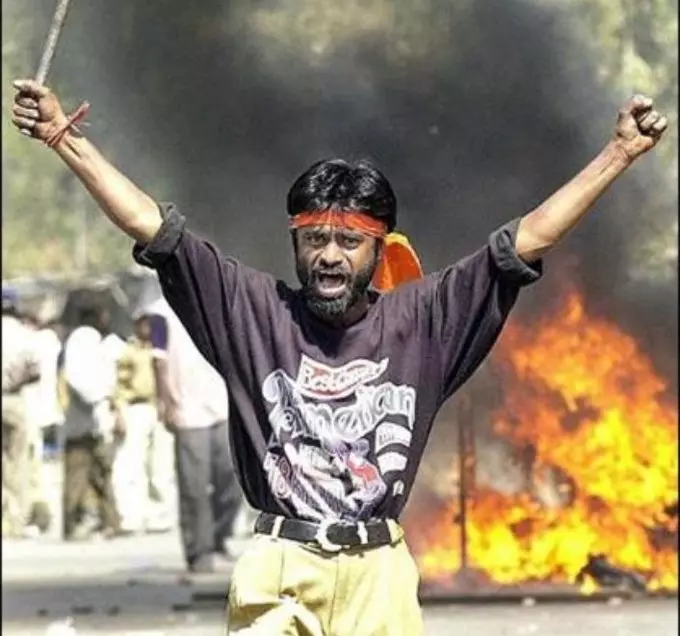

Ashok Mochi, a Dalit man, whose face became a symbol of the riots with a saffron band around his head and a steel rod in one of his hands, also joined the Dalit Muslim solidarity platform post Una incident that were spearheaded by Dalit leader and Congress MLA Jignesh Mevani.

In 2002 | Ashok Mochi, a Dalit man, whose face became a symbol of the riots with a saffron band around his head and a steel rod in one of his hands,

In over 20 years, Mochi has distanced himself from Bajrang Dal. Out of jail in 2020, after serving 10 years under rigorous imprisonment for the Naroda Gam riot case, Mochi now works as a cobbler on the footpaths of Shahpur area in Ahmedabad and lives in an adjoining school.

“Whatever I earn is hardly enough to provide food and clothing much less a house,” he says.

Noticeably, Mochi, along with six other Dalit men, was found guilty in the case while prime accused former BJP Minister Maya Kodnani, Bajrand Dal leader Babu Bajrangi and VHP leader Jaideep Patel were found innocent.

“I am single. The photograph as the face of Hindu aggression during the riot and then a case against me are the primary reasons that nobody married me. Besides I am poor. Even after 20 years, no one from VHP, Bajrang Dal, BJP or RSS have come to offer me any financial help,” shares 45-year-old Mochi.

Noticeably, after the 2002 riots, 27 cases were filed in different districts of the state. By the year 2023, 205 accused were acquitted in these cases including BJP leaders Maya Kodnani, VHP leader Jaideep Patel, around dozen BJP former corporators and VHP and Bajrang Dal members belonging Patel communities.

Thirty-seven men were found guilty in the 27 cases and were awarded punishment ranging from ten years of rigorous imprisonment to life imprisonment. All these men, barring Bajrang Dal member Babu Bajrangi belong to the Dalit community.

Ashok Mochi in 2025

Babu bhai Patel or Babu Bajrangi, as he is known, was the prime accused in 10 of the 27 cases. However, he was acquitted in all of them except the Naroda Patiya case where he was awarded life sentence. He has been granted bail 17 times since his imprisonment in 2009. Currently, he is out on parole on ground of deteriorating health conditions.