- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How two suicides in UAE uncover the plight of Kerala’s dependent migrant women

The suicides of two young Malayali women in Sharjah expose a trail of domestic abuse, isolation, and systemic neglect faced by dependent migrant wives, women who remain undocumented in the foreign land

Two suicides by expat women in the United Arab Emirates, which shook Kerala, has turned the spotlight on a niche vulnerable group, hitherto not acknowledged or largely overlooked since these women live ‘invisible’ lives. Falling in the bracket of dependent migrant women, these women have trustingly moved to foreign, unfamiliar lands, tagging along with their husbands. Away from...

Two suicides by expat women in the United Arab Emirates, which shook Kerala, has turned the spotlight on a niche vulnerable group, hitherto not acknowledged or largely overlooked since these women live ‘invisible’ lives. Falling in the bracket of dependent migrant women, these women have trustingly moved to foreign, unfamiliar lands, tagging along with their husbands.

Away from their loving families in a country, which largely see them as outsiders, there is no one to turn to when life gets stormy, except the man they have tied their destiny to. And, what if the husband is the one who shatters their dreams and turns into an oppressor? Besides, the husband holds all the cards as these women are on their spouse visa, making them highly vulnerable.

So, if there is marital strife and domestic harassment, these women feel completely alone and abandoned. The conservative family back home in India may not want to shoulder the failure of a broken marriage. Vipanchika Maniyan, a 33-year-old woman from Kollam, Kerala, was one such woman, who ostensibly found she had nowhere to turn to.

On July 8, 2025, Vipanchika and her one-and-a-half‑year‑old daughter Vaibhavi were found dead in their Sharjah apartment. Medical and forensic inquiry in the UAE suggests that Vipanchika ended her own life after suffocating her child. According to reports, it was a case of murder and suicide rooted in alleged relentless intimate partner violence and domestic harassment.

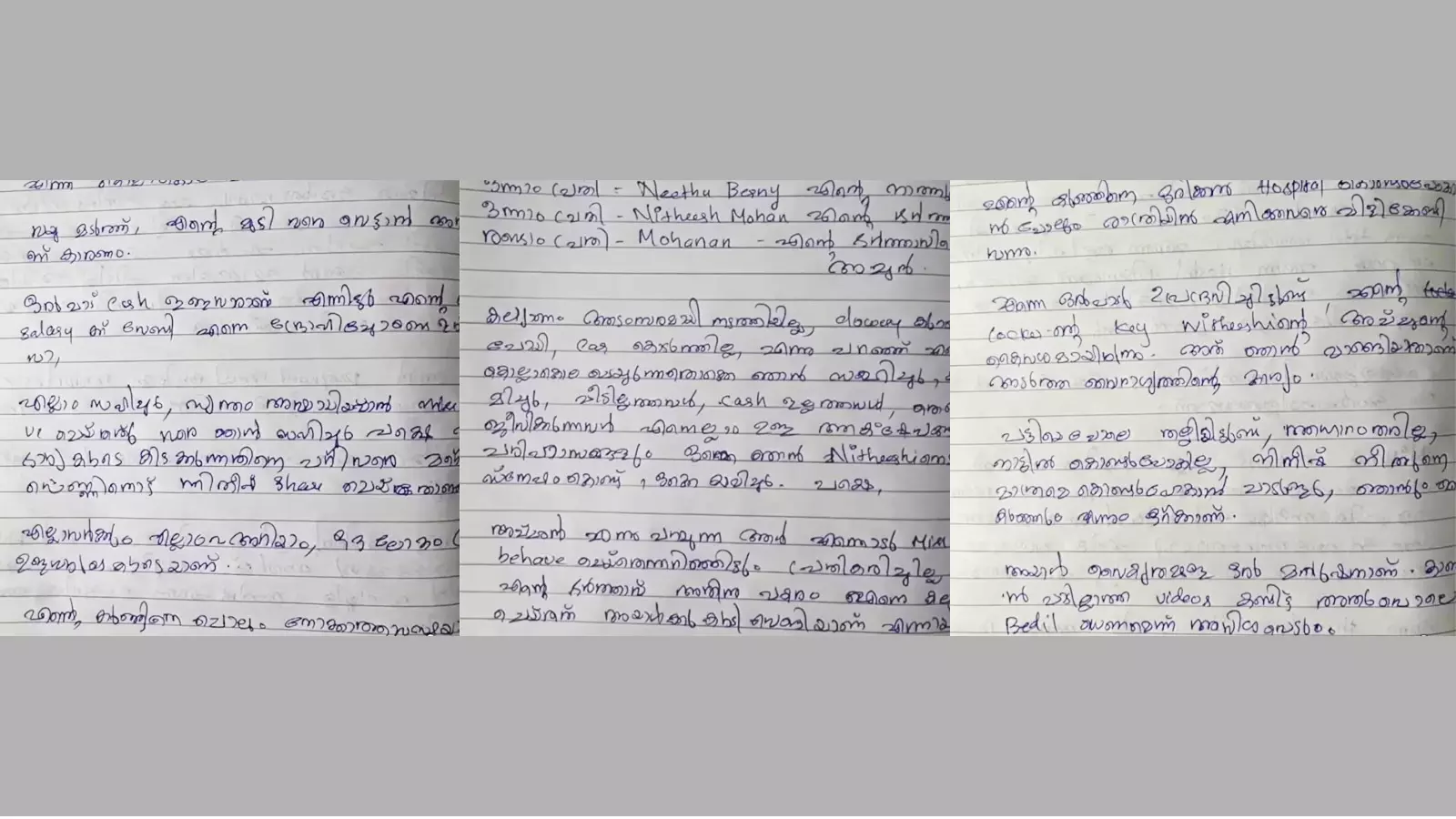

A short-lived Facebook ‘suicide note’ allegedly posted by Vipanchika, named her husband, father‑in‑law, and sister‑in‑law as perpetrators of severe physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, describing her as allegedly being ‘beaten like a dog’, and pushed out of her home while pregnant. Besides, she was also forced to shave her head to diminish her fairness. The note also hinted at incestuous abuse by her father-in-law and pornographically-inspired sexual harassment by the husband.

Also read: In Uttarakhand’s Tehri Garhwal, women help boost rural tourism as nature guides

A painful dispute followed over final rites. Her mother, Shailaja, travelled to Sharjah and demanded that both bodies be repatriated to Kerala, along with a re‑postmortem. Despite a Kerala High Court order requiring central and consular authorities to facilitate the return of Vipanchika’s remains, her husband insisted that Vaibhavi be cremated in Sharjah.

A mediated agreement resulted in Vaibhavi being cremated in Sharjah, while Vipanchika’s body was transported to Kerala and cremated there after a formal re‑postmortem.

Thus, mother and daughter remain physically separated even in death — one laid to rest far from home, the other returned to be mourned — and the circumstances that led to their deaths remain under investigation by cross‑border authorities.

Days after Vipanchika’s suicide, on July 19, 2025, 29-year-old Athulya Satheesh, originally from Kollam, Kerala, was found dead in her Sharjah flat.

In the hours before her death, she had shared video-clips with friends showing bruises, threats, and physical assaults from her husband, incidents of torture that had been going on since their marriage in 2014. Some accounts indicate she had submitted complaints to Sharjah police earlier, but no protective action was taken.

She was due to join a new design job the day she died. Athulya’s recorded last pleas offer a haunting testimony to what her life had been.

A short-lived Facebook ‘suicide note’ allegedly posted by Vipanchika, named her husband, father in law, and sister in law as perpetrators of severe physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

Athulya’s parents, after returning from Sharjah, lodged a formal complaint alleging prolonged physical, verbal, and dowry-related abuse. Local police in Kerala registered a case under appropriate criminal sections against the husband and father-in-law.

These two linked incidents illustrate the harsh realities of dependent migrant women subject to domestic cruelty, physical and sexual violence, and legal invisibility under visa restrictions. Together, they begin to frame a broader story of vulnerability and systemic neglect in dependent-gendered migration frameworks.

“These suicides are not just shocking incidents, they are symptoms of a much larger crisis we haven’t acknowledged: women living invisible lives, with no help, no voice, and no way out. We must start talking about this, openly, urgently, and with compassion,” says Nisha Ratnamma, independent journalist and educator based in the UAE.

“In both cases, the pattern is painfully similar. It starts with emotional manipulation disguised as love, like ‘I don’t want you to work because I care for you’ and then comes the slow isolation. These women are gradually cut off from family, friends, even neighbours. They are confined to the four walls of a flat, with no emotional outlet or support. Back home, even if her parents sense something is wrong, they may tell her to adjust, suffer, or stay for the sake of the children,” points out Ratnamma.

“Many women from Kerala come to the Gulf with the hope of building a better life eager to work. But they often lack language skills, confidence, or access to the right networks. And those who are not educated are even more vulnerable with limited opportunities and due to the complete financial dependence, they become easy targets for control and abuse,” adds Ratnamma.

Academic and sociological studies on migration have long focused on labour migrants, particularly men whose movements are traceable through employment records, visa categories, and remittance flows. In this framework, dependent women migrants, especially those who accompany their spouses to the Gulf countries on family or spouse visas, are often unnoticed.

Also read: Pulicat women bottle palm nectar, revive Tamil Nadu’s neglected palmyra trees

Generally, these dependent women do not earn wages, many of them do not send remittances, and are largely absent from public records or migration data. As a result, they remain statistically invisible despite playing significant roles in the transnational migration ecosystem as caregivers, homemakers, and emotional anchors in migrant households.

Their economic invisibility also contributes to policy blindness. Since they are not recognised as workers or economic contributors, their vulnerabilities such as isolation, legal dependency, domestic abuse, and lack of access to support systems remain unaddressed in both home and host country.

Moreover, the remittance-based understanding of migration treats income as the primary marker of participation and success, reinforcing a gendered blind spot. It ignores the structural constraints that prevent these women from entering the labour market, including visa restrictions, patriarchal control, and social expectations around gender roles.

The two women, who took their own lives, may not strictly fit the typical profile, as Vipanchika held a well-paying job as an HR manager and Athulya was about to start a respectable position. However, their suicides have drawn attention to the dependent visa status under which both had migrated to the Gulf.

The government, too, is gradually waking up to the problem. K.V. Abdulkhader, chairman, Kerala Pravasi Welfare Board, tells The Federal: “Generally, there has been a widespread belief that couples, especially wives or partners, would be psychologically better off living together rather than being separated across countries.”

However, the recent shocking incidents of two women and a child taking their own lives, have deeply shaken that assumption, he adds. “This is a new reality and an emerging social phenomenon. The government is taking it seriously, and as a society, we must begin to address this issue with a fresh perspective. We are currently exploring various solutions.”

Often, the husband has the upper hand since he can cancel his wife’s residency permit if he wants to snap ties with her. Take the case of Jumaina (name changed), 38, a postgraduate in physics from central Kerala, who lived in Ajman for nearly a decade. Her expat life ended abruptly after she questioned her banker husband’s extravagant lifestyle. In retaliation, he threw her out of their flat in the middle of the night during the COVID pandemic and cancelled her residency status for that single act of defiance.

“I migrated to the UAE after our marriage in 2011. I was 23 then, just out of college. I wanted to work, and initially, he supported that. I even joined an IT firm and worked for a few months. But when I became pregnant, I had to quit. Then I had a miscarriage and everything changed,” shares Jumaina, now a higher secondary school teacher in Kerala.

“After the miscarriage, I developed some health issues. That’s when he began to distance himself. He started ignoring me and spending every night out, living what seemed like an extravagant nightlife. When I began to question this, everything escalated,” Jumaina recounts.

“I was literally locked inside the flat, sometimes he even took the key with him when he left,” Jumaina recalls. “When I finally confronted him, it turned violent. He assaulted me and then threw me out of the house. I had to spend an entire night in a friend’s car. Within a week, he cancelled my residency permit. That was the beginning of the end; it eventually led to our divorce.”

So, the threat of cancelling the spouse visa is often deployed to force the women into submission. “For many husbands, cancelling the spouse visa becomes a tool to force obedience. Women, often unaware of the rules and regulations of the host country, are left with no real options. They either have to comply or return home,” says Honey Bhaskaran, a Dubai-based Malayalam writer.

Migrant dependent women remain statistically invisible despite playing significant roles in the transnational migration ecosystem as caregivers, homemakers, and emotional anchors in migrant households.

“In many Gulf countries, wives can work even on a dependent visa, provided they obtain a work permit. However, once the husband cancels the spouse visa, the woman loses her legal right to stay. Even if she is employed, she is left with no choice but to leave the country,” points out Bhaskaran.

Honey, 40, has been in the Gulf for the past 15 years and is a single mother who went through this ordeal in her own life. “Even after having a job visa, life as a single mother has been the most difficult phase I’ve ever faced. I hadn’t worked while on a dependent visa, and later, despite being employed, I had to send my two-year-old son to live with my mother back home. Many expatriate women choose not to tell their parents about the domestic abuse they go through, just to spare them the stress and emotional pain,” she explains.

Further, she says that dependency isn’t always the reason behind domestic violence among expatriate Malayalis. She knows several people, including financially independent professionals like doctors, who have faced such abuse, says Bhaskaran, adding that one doctor she knew was severely beaten by her husband. Bhaskaran got involved in the case and was able to help her then and she eventually got a divorce.

“Because of the strict laws in Gulf countries, many women hesitate to report abuse by their spouses. They often feel guilty, fearing that taking action might ruin the life of their child’s father since Gulf countries take such crimes very seriously. This guilt is one of the reasons why many abusers manage to escape accountability,” points out Honey.

Somy Soloman, a researcher in one of her presentations about dependent migrant women from Kerala, argues that patriarchy and hierarchies of power equip men to dominate the narrative of migration.

“Man gets preferential access to available resources in the society through his power to rule over women. As the dependent migrant women are not part of remittance, her contributions are invisible in the historical narrative,” says Soloman. (However, it has to be noted here that not all dependent women migrants are not part of remittance.)

Women’s position in the host country determines the authority within the family and the sense of control and access to financial matters. According to Soloman, who herself was a dependent migrant in Tanzania for eight years, the social location of the host country determines the position of a ‘dependent woman’ in that country. The position of ‘dependent woman’ in Europe will be different from the social position of ‘dependent woman’ in West Asian countries. The social position of ‘dependent women’ will be different in an African country compared to Europe and West Asia.

The religion, caste, social class all derive the social position and the rights and freedom ‘the dependent women’ enjoy in the society. “In my personal life, I have experienced what it feels like to have your existence reduced entirely to being someone’s spouse. You are seen as nothing but a wife, even legally. The most painful part is how easily women in this position are made invisible,” Soloman tells The Federal.

“Digital access and virtual spaces have become the only avenues for many dependent women migrants to express themselves today. Even this is a relatively recent development, and many are using it simply to assert their existence,” Somy adds.

Also read: How women from Telangana’s Irkode village built a global meat pickle brand

“In the nine years and ten months I lived in the UAE, I never met a single person there without my ex-husband being present. For months, he would lock me inside the flat while he went to work. It felt like being literally in a prison, with comfort, food, and sex, but no freedom,” says Jumaina.

Rejitha Hari (name changed), 36, had been living in one of the GCC countries for a decade with her husband. Migrating in 2013 on a family visa, she soon began teaching classical dance to children, an art form she had trained in. Within a couple of years, her dance classes were doing well and she was earning a modest, independent income.

“At first, my ex-husband was supportive. In a way, we were running the classes together,” Rejitha recalls. “But once I started making money of my own, he became insecure. He couldn’t handle me having financial independence.”

What followed was a gradual descent into domestic abuse. “He started doubting me, accusing me of things, claiming I had affairs with the fathers of my students, and god knows who else,” she remembers. Within three to four years, life became “unbearable” and Rejitha had to move out.

What came next, Rejitha says, was almost predictable. She returned to India, only to be served divorce papers. “I knew going back to that life would ruin my mental health. A relatively supportive home environment is the only reason I survived.”

As a researcher, Soloman feels that the presence of dependent migrant women must be acknowledged in migration narratives, studies, and policies. These so-called ‘invisible women’ need to be brought into both academic and public discourse. She believes that as an academic category, dependent migrant women deserve deeper research and more focussed interventions to better understand their specific challenges and the roles they play within migrant communities.

While many studies suggest migration has improved the economic status of women in migrant families, often pointing to better living conditions and opportunities for the next generation, this picture does not capture the full reality. These gains are largely statistical and do not reflect the lived experiences of many women, especially in Gulf countries.

Within expatriate households, women’s dependence remains deeply rooted. Their roles are often limited to caregiving and household responsibilities, with little room for autonomy or personal growth. Despite contributing significantly to the stability of migrant families, these women are rarely recognised as independent individuals with rights and aspirations.

Most migration studies have failed to examine or even acknowledge this lack of agency. The focus has remained on economic indicators while ignoring the critical question of whether women within these families are able to lead independent, self-directed lives. This silence has allowed the structural inequalities they face to persist, unaddressed and unchallenged.