Writer B Jeyamohan

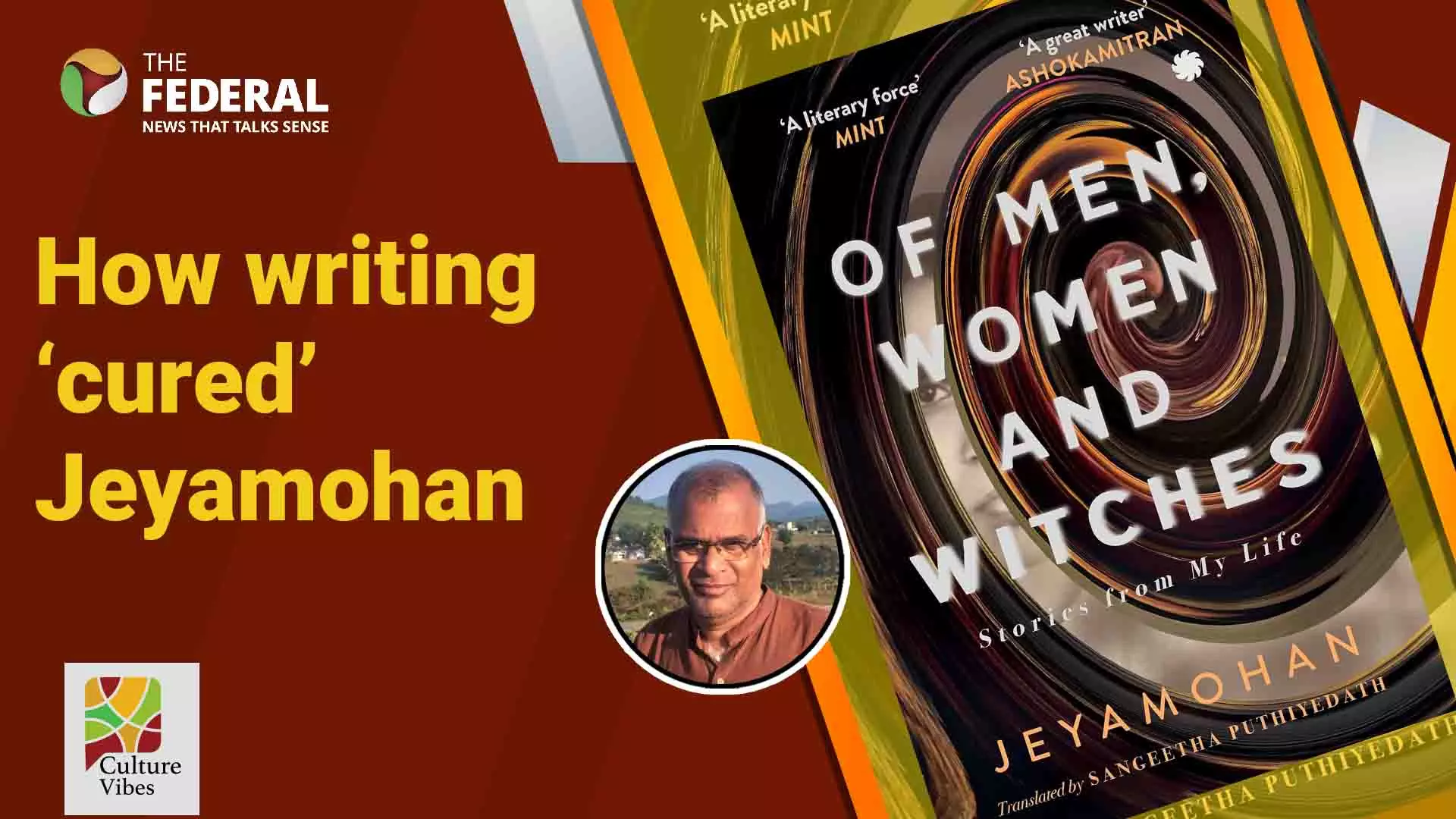

Jeyamohan interview: ‘Devastated by my mother’s death, I found refuge in writing’

Tamil writer Jeyamohan opens up about his memoir, Of Men, Women and Witches: Stories from My Life, his unhappy childhood, why great human dramas are best way to fight identity politics, and more

In the latest episode of Culture Vibes, The Federal’s special programme on arts and literature, celebrated Tamil-Malayalam writer B Jeyamohan, who lives in Nagercoil, Tamil Nadu, spoke about his memoir Of Men, Women and Witches: Stories from My Life (Juggernaut), which has recently been translated by Sangheetha Puthiyedath. A collection of personal essays, it was first first published in Malayalam in 2011 as Uravidangal, and gives a glimpse of Jeyamohan’s early life in the village of southern Tamil Nadu (part of old Thiruvithamkoor). It was also made into a Malayalam movie, Ozhimuri (Divorce Record), in 2012.

In the interview, Jeyamohan opened up about his memoir, literary choices, and the evolution of identity politics and serious fiction — his matriarchal childhood and meditative writing practices. His insights span decades of literary and cultural transformation, all rooted in personal tragedy, philosophical inquiry, and a writer’s quest for meaning.

Matriarchal roots and family influence

Jeyamohan reflects on his childhood in a matriarchal Nair household near the Tamil Nadu–Kerala border. He contrasts this upbringing with patriarchal Tamil society, which, he argues, often strips women of power after marriage. “Suddenly, one day a woman can become poor. Her father is still rich, but she is left with nothing,” he observes.

For Jeyamohan, the strength of his mother and grandmother left a lasting imprint. “They were scholars. They had their own land dealings, court cases, and culture. They were free women,” he says, affirming his deep respect for the matrilineal order, which nurtured independent, land-owning women with strong sibling bonds—especially among sisters.

The shaping power of literature

Jeyamohan recounts how early Malayalam romantic literature, particularly the poem Ramanan, by alayalam poet Changampuzha Krishna Pillai, shaped his mother’s worldview. “My mother had an obsession with suicide. She loved Ramanan. It was part of a literary wave then—suicide was glorified in literature and film,” he says. These cultural currents tragically influenced his mother, who eventually took her life.

He further notes that he is “truly bilingual,” deeply rooted in both Tamil and Malayalam literary traditions. This duality enriched his sensibility and deepened his ability to see nuances in social structure, gender, and personal loss.

Memoir, memory, and mourning

His memoir, Of Men, Women and Witches was born from a request by his editor at Mathrubhumi. “I started to write personal narratives,” he says. The stories also inspired a Malayalam film, which won a national award. “It’s probably the first time a non-fiction book became a film,” he notes.

Reflecting on personal trauma, he says, “It’s not the loss of my parents that haunted me, but the loneliness after their death.” His parents both died by suicide, triggering years of emotional imbalance and insomnia. “I couldn’t sleep for more than two hours a day,” he recalls.

Writing as healing

“I found refuge in writing. It was curing me,” he says. Writing became not just a profession but a spiritual act. During the COVID lockdowns, he wrote 136 short stories—one a day. “Writing is my meditation. What meditation was to Buddha, writing is to me.”

His writing offers emotional connection and transformation. “A mother of a writer never dies. She lives through his words. That’s what I believe,” he adds, tearfully recalling vivid memories of his mother.

Literature vs identity politics

Jeyamohan expresses strong views on the dominance of identity politics in literature. He does not oppose it but seeks to transcend it. “I’m not fighting it. I ignore it. I’m trying to create a holistic picture—a non-religious spiritualism,” he says. His philosophy leans toward Gandhian “micro politics,” which involves working with women, tribal groups, and the marginalised at a grassroots level.

He rejects state recognition, including the Padma Shri. “I said no. I don’t accept awards from government or government institutions,” he asserts.

Language and literary culture

Jeyamohan critiques the decline of multilingualism and deep language engagement among India’s youth. “Even urban kids in Tamil Nadu can’t read a page of Tamil,” he laments. However, he finds hope in a new generation of translators like Priyamvada and Suchitra Ramachandran, who, despite their English education, are returning to Tamil out of personal interest.

“Multilingualism is no longer a talent,” he says, noting that today’s knowledge economy depends on metalanguages and analytical tools rather than literary language.

On serious vs popular writing

Jeyamohan draws a firm line between commercial and serious literature. “Commercial writing is consumer-oriented. Serious writing is writer-oriented,” he explains. He likens commercial fiction to a product engineered for mass taste, whereas serious literature is an invitation for the reader to step into the writer’s world.

He also critiques postmodern literary criticism, saying it eliminated distinctions between pulp and high literature. “In Tamil, critics still hold that line. But not in English or American academia,” he points out.

A writer’s legacy

For Jeyamohan, literature is a medium of direct, emotional communication. “The stories are tools. I am the spider behind the web, waiting for the reader to connect,” he says. He shares a spiritual bond with writers like Dostoevsky, Shivaram Karanth, and Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay—writers who transcend time to engage directly with the reader’s soul.

“There is always an intelligent reader somewhere. You cannot cheat them with formulas,” he asserts. According to him, serious literature is an intimate communion, not mass entertainment.

B Jeyamohan’s journey from trauma to transcendence is marked by literary conviction, spiritual inquiry, and defiance of consumerist culture. Whether it’s rejecting state honours or resisting identity-based categorisation, his voice remains singular and uncompromising.

In the interview on Culture Vibes, this deeply personal and philosophical conversation illuminates not only his creative journey but also the enduring role of serious literature in a fast-changing world.

The content above has been generated using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.