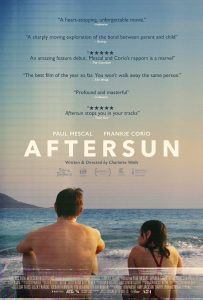

'Aftersun' review: Disruptive, heartbreaking and personal

'Aftersun' depicts an unvarnished portrait of a young man grappling with responsibilities, struggling to hold on to his own life while willingly shouldering responsibility of another. Rarely has a film been so empathetic towards a parent while siding with the child

There is this memory of my father I keep going back to: he is sitting on the bed and asking me what is the matter. I have thrown a tantrum because I want a new dress. My mother is staring at me, livid, even as her lips are moving audibly in evening prayer. The next thing I remember is Baba carrying me in his arms and climbing the stairs of a shop. I have no memory of the dress or Ma accompanying us. But the tangibility of that embrace — a middle-aged man carrying his young truant daughter with both their chests heaving in unison — is etched in my mind.

Watching Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun felt like revisiting that decades-long moment over and over again. It felt like I could hear that memory, listen to him run out of breath. Like I had. And then midway through the film, I could see my father’s face turn ashen with exhaustion. But in the image that persists in my mind, he has no face. All I remember from that summer evening is clutching my father’s shirt tightly and staring at my grasp as it swayed with every step.

Also read: 40 years after ‘Arth’, Hindi cinema’s elusive quest for women empowerment

That’s the thing with memory: you inhabit it in totality but the mind captures it in fragments. When I held hands with the one I loved for the first time, all I had seen were two pairs of eyes staring at me. That is my enduring memory although the moment was different.

Language of remembrance

In her distinct, startling feature debut, Wells frames the story around a father-daughter relationship and conveys it through the language of remembrance. Describing Aftersun this way makes it seem ordinary. But this speaks more of Wells’ towering achievement and less of the inherent limitation of the written word.

Memory has forever served as the bedrock of art. Artists draw from their lives to create something new. In doing that, they seek narrativising their past and embellishing it with the merit of experience. Wells’ singular achievement resides in her refusal to do so. The Scottish filmmaker has not just made a film on how a daughter remembers her father, but mapped out a unique cinematic language that mimics attributes of memory in all its untranslatability and, perhaps even, unreliability. Her ambition is so purist in intent that it feels radical in execution.

Aftersun opens with handheld footage of a daughter trying to capture her father in a camcorder. He breaks into a dance and we hear her voice from behind, curling in embarrassment. Sophie (Frankie Corio) is 11, her father Calum (Paul Mescal) is 30. His birthday is in two days. The grainy footage is from a trip they took in Turkey. In a matter of seconds all gets blurred and the blank screen outlines a silhouette. Someone was watching the recording. This moment appears briefly but it underlines the throbbing soul of the film, hinting that what we are witnessing is a piece of art that dares to look at memory through the pinhole of another memory. The composite image from afar is that of a grown daughter looking at what she remembers of her father while confronting how she wanted to remember him.

Layered reminiscences

Wells’ outing, designed as a layered stack of reminiscence, centers around their trip – the few days they spend together, dancing, breaking into uncontrollable laughter and sometimes snapping at each other. They take dives together, laze around the pool watching the sky. Calum swathes lotion on Sophie’s back as she, an adolescent on the cusp of teenage, looks at the world with a pair of eager eyes.

Also read: RRR, All That Breathes find a place on BAFTA 2023 longlist

We get an idea that Sophie’s parents are separated amicably. Calum has left Scotland and harbours no wish to return. He has outgrown the place, he says. These moments, brimming with tenderness and intimacy, unfold like they are overlapping on each other. Like, they are spiraling from a grown Sophie’s memory. The form Wells adapts to showcase this slipperiness feels disruptive for being so immersive (Gregory Oke is the cinematographer).

At nights, when Calum stands outside the balcony and Sophie lies on the bed, the frame is punctuated with the sound of her breathing; as if she is pretending to sleep, all too aware of her pretension, and watching her father for longer than she can. When they are together, the camera trails back to the image of their hands, clumsily intertwined. The implication is still the same: this is what Sophie remembers from the moment; the tactile intimacy is what she continues to hold close.

But Aftersun is not just about looking at things, it is also about looking back. It is about a woman, now as old as her father was when she was 11, looking at a picture from her childhood and shifting her gaze to her parent — recognising, probably for the first time, vestiges of him buried in her instead of looking for herself in him. It is about an adult looking at another with belated empathy. More tellingly, it is about a daughter reliving her father’s memory in intricate details because maybe that is all she has.

Imagined recollections

Keeping with the aesthetic craftsmanship of the film, these insinuations are subtle but definitive. The older Sophie has a child with her partner. She is queer. This simple fact underlines her own beleaguered status, making her more attuned to the pathos of her then young father. Her memories from the trip are interspersed with imagined recollections. The gap between what had happened and she had seen is filled with her assumption of what might have unraveled.

There is a scene of both of them in Turkey at a carpet store. Calum asks the price and with a diffident smile makes it clear he cannot afford it. Later, we see the same carpet at Sophie’s house. We don’t see him buying it but we do see Calum, as the adult Sophie might have envisioned later, lying down on the carpet alone, marinating perhaps in his inadequacy of providing his daughter what she wants. In another scene, right after his birthday, we see him sobbing in a room alone. Rarely has a film been so pointedly on someone and yet unfolded as a story of someone else.

Across its runtime, stitched together with the real and the invented, Aftersun depicts an unvarnished portrait of a young man grappling with responsibilities, struggling to hold on to his own life while willingly shouldering responsibility of another. Rarely has a film been so empathetic towards a parent while siding with the child. Mescal’s face radiates with the heartbreak and humiliation from assuming a role he is not quite prepared for. In many ways, Calum is a theoretical extension of Connell, his character from Normal People.

Calum is what Connell would have been after graduating from college: married young, had a child and increasingly disillusioned with life. Both characters share a similar texture of incurable emotional isolation and Mescal is terrific in how he evokes so much with so little. In the scene when his character tells Sophie that he has outgrown Scotland, Mescal’s face tells another story: the place has outgrown him. Corio as Sophie is a revelation. She is intuitive, eager, cruel and sympathetic at the same time. Her face distills the follies and vagaries of youth.

Also read: AR Rahman announces launch of new digital music platform, ‘Katraar’

The strange bit of Aftersun is how tragic it feels despite most of the film being imbued with the dappled warmth of companionship. The sucker punch of a last scene accentuates this reading but it is mostly for Wells’ ability to uncover the primal trait of memory: to remember is to mourn. We never really know what happened to Calum after the trip (though there is an inkling of him dying). But even without such confirmation, it breaks your heart to see a daughter rewinding the accumulated memories of her father.

It is the same reason why, as a 30-year-old living away from my father, I keep reliving that evening. I look back to convince myself that he wasn’t always a 70-year-old frail man. That once upon a time he was robust and agile and didn’t need to lean on me to do something as basic as walk. Maybe Aftersun is a similar exercise in mourning where a daughter, stung by the cruelty of time, looks back to persuade herself that things were not always like this. That before the gloominess of dusk, there was a hope of dawn. But to look at dawn in retrospect, to live in this land of aftersun, is the tragedy.