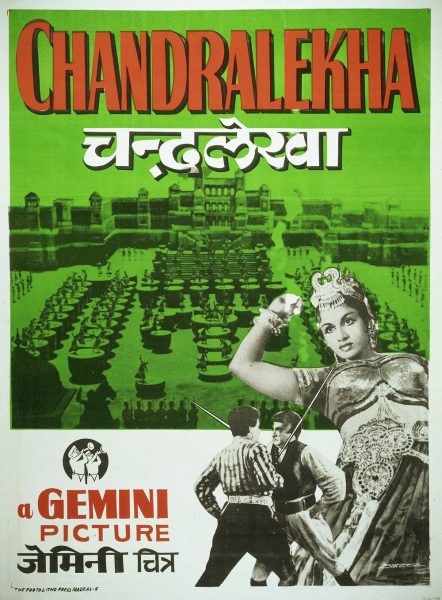

How ‘Chandralekha,’ a 1948 Tamil film, paved the way for big-budget Indian films

As SS Vasan's masterpiece celebrates its diamond jubilee this year, a look at how it marked a turning point in the history of Indian cinema

Seventy-five years ago, Chandralekha, the first big-budget Tamil film, released on April 9, 1948. It marked a momentous occasion, and a turning point, in the history of Tamil cinema and Indian cinema as a whole. Produced and directed by media mogul SS Vasan, this big-budget film broke new ground by incorporating elements of entertainment on screen.

In December of the same year, the film was also dubbed in Hindi, which opened up new markets for Tamil films in North India. “Vasan’s film marked the first real assault on the Hindi film market, and he captured it with masterly ease. His success paved the way for a series of Hindi films from the South, made under the banners of AVM, Vauhini, Prasad, and Devar,” said P Neelakantan, former principal, MGR Government Film and Television Institute, Chennai, in his article “Progress of Tamil Cinema,” in Fifty Years of Indian Talkies, 1931-1981: A Commemorative Volume, published by Indian Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Bombay, 1981).

As Chandralekha celebrates its diamond jubilee this year, revisiting the film provides insight into the commercial elements that SS Vasan introduced in his work. Though it required a significant investment, it elevated the film to new heights, and laid the foundation for big-budget films in the Tamil film industry, long before the term ‘pan-India’ became popular in trade parlance.

The story of inspiration

It is interesting to note that some production houses in Tamil film industry, like Vasan’s Gemini Studios in Chennai, had their own “story department”, where a group of writers, after many brainstorming session, came up with a script. They would get a collective credit — “kathai: kathai ilaakaa” (Story: Story Department) — instead of an individual writer’s name.

Drawing inspiration from the works of American film producer and director Cecil B. DeMille, who was famous for movies like The Ten Commandments (1923), Vasan aspired to create a grand and captivating entertainer. To achieve this goal, he tasked his story department with developing a script that could showcase his vision’s grandeur and spectacle.

Before Chandralekha, Gemini Studios had made successful heroine-centric features like Mangamma Sabatham and Balanagamma. They were written by Gemini writers, like Kothamangalam Subbu, Ki. Ra. Sangu Subramaniam, Veppathur Kittoo, and others. After the success of the two films, the writers came up with another heroine-centric story.

“When Vasan’s story department pitched the story of a tough and talented woman who outwits a vicious bandit, culminating in the ultimate insult of slashing off his nose and filling the bloodied wound with hot, red chili powder, Vasan initially found it too gruesome, crude, and vulgar. However, the name of the woman, Chandralekha, stayed with him even after he dismissed the story,” says film historian Randor Guy.

Also read: Tamil film ‘Narai Ezhuthum Suyasaridam’: Poignant study of post-retirement life

After three months, the story department presented Vasan with a script that drew inspiration from the English novel, Robert Macaire: Or, the French Bandit in England (1856) by George WM Reynolds.

‘A small kingdom’

Gemini Studios began shooting the film in 1943, and over the next five years, it went through a series of re-writes, re-shoots, and re-edits, ultimately costing over Rs 3 million. “It was the most expensive movie made in India till then,” writes Guy in his book Starlight, Starbright: The Early Tamil Cinema (1997). He further adds that Gemini Studios, located in the heart of the city, thereafter became a bustling hub of film-making activity.

Kothamangalam Subbu, the film’s assistant director, reminisced years later about the production process of Chandralekha, stating, “During the making, our studio looked like a small kingdom… horses, elephants, lions, tigers in one corner, palaces here and there, over there a German lady training nearly a hundred dancers on one studio floor, a shapely Sinhalese lady teaching another group of dancers on real marble steps adjoining a palace, a studio worker making weapons, another making period furniture using expensive rosewood, set props, headgear, and costumes, Ranjan undergoing fencing practice with our fight composer ‘Stunt Somu’, our music directors composing and rehearsing songs in a building… there were so many activities going on simultaneously round the clock.”

Circus, elephants, choreography

The main reason for the film’s enormous success was the incorporation of elements such as circus, elephants, and grand choreography within the script, instead of adding them as mere embellishments. For instance, the character of Chandralekha (played by TR Rajakumari) rescues Prince Veerasimhan (MK Radha) with the help of elephants from a circus troupe.

“The sequence of elephants moving in a single file on a mud track, followed by cages with big cats and clowns singing a lively song, is one of the most memorable moments in Indian film history,” writes S. Theodore Baskaran, a film historian and environmental writer, in his 2013 article “The Elephant in Tamil Films,” written for Hasti, a symposium on elephants.

In the later part of the film, Chandralekha is seen trying to escape from the clutches of the villain Sashankan (Ranjan) by taking refuge with a circus troupe, where she eventually becomes a gymnast herself. The movie’s screenplay required scenes depicting circus performances and artistes’ training sessions, making it one of the earliest Tamil films to feature an actual circus troupe. This proved to be a major attraction for audiences at the time.

Also read: Sarjun KM interview: ‘Burqa’ sprang from real-life experience, not against purdah

Vasan, who believed in creating spectacle for the masses, had a particular fondness for elephants, in addition to his love for race horses, and used them extensively in two of his films, he adds. “In 1948, visitors to the Gemini Studios’ campus in Madras would have been surprised to see numerous elephants being kept and looked after there, making it look like an elephant camp,” says Baskaran.

“During the shooting of Chandralekha, which was being filmed at the time, two famous circus companies, Kamala Circus and Parasuram Lion Circus, were camped on the studio grounds. After the movie’s completion, at least one of these companies changed its name to Gemini Circus,” he adds.

It’s worth noting that since Chandralekha, many other Tamil films have used elephants as an entertainment factor, primarily to attract children.

In the climax of the film, there was a grand dance sequence arranged by the heroine. Dancers performed on a number of tall and big drums, inside which the hero’s men were hiding, waiting to come out and fight the villain. The scene was reminiscent of the Trojan Horse and created a thrilling moment for the audience.

“Vasan had nearly 400 dancers on monthly salary, and they had daily rehearsals for six months; that single sequence cost Vasan Rs 5 lakh (half a million) in the 1940s, it was said. The man who designed all this was Chief Art Director A.K. Sekhar, whose contribution was palatial splendour. The two music composers, M.D. Parthasarathy and S. Rajeswara Rao, created a wonderful blend of music styles, including Carnatic, Hindustani, and even Western music such as waltzes and jazz. Many of the songs from the movie became hits,” says Guy.

The impact of Chandralekha

To top it all, Vasan launched a massive publicity campaign that made the nation sit up and take note, adds Guy. “His budget was said to have been nearly a million rupees, an incredible sum in those days. Full-page ads, huge multi-coloured posters, glossily printed brochures, press books, expensively printed songbooks, were to be seen everywhere… it was all unheard of in India,” he writes.

P Thirunavukkarasu, editor, Nizhal, a film magazine, tells The Federal that it was after the success of Chandralekha that Bollywood gained confidence to create huge sets. “After watching the film, noted filmmaker V. Shantaram expressed his concerns about the survival of Hindi cinema if Tamil films continued to spend money like this. The huge sets erected by Gemini Studios commanded awe and respect, and it was this film that inspired and gave courage to Bollywood to create grandiose productions like K. Asif’s Mughal-E-Azam (1960),” he says.

Also read: Jubilee review: A lavish ode to Hindi cinema, an epic tale of ambition and stardom

However, Baskaran offers a different perspective. While many claims have been made about the film, such as it having 200 prints at the time of its release, the film itself does not make any social commentary, he notes.

“The film’s sole purpose is entertainment. The makers did not concern themselves with the period of the story, which includes fencing fight scenes and guns, with no clear mention of place,” he says. “However, it was this film that established the norm that an entertaining film should have dance, fight sequences, and a male gaze as main ingredients. Chandralekha made a lot of money, which is why the same formula is still being followed in Tamil cinema today,” he adds.

Baskaran goes on to criticize Chandralekha for lowering the standards of Tamil cinema. He notes that while this film was being made, it was at the same time that movies like Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) were being produced in other parts of the world.