Cheetahs in India will outrun their foes: Expert overseeing relocation programme

There will be occasional deaths of cheetahs in Kuno, Madhya Pradesh; a few could even be attributed to septicaemia triggered by radio-collars as well as other reasons such as infighting and getting killed by more powerful predators. That’s inevitable.

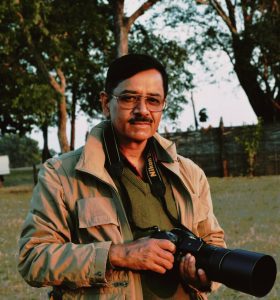

But rest assured the world’s fastest runner will overtake these “periodic hiccups” and eventually adapt to India like fish to water, points out Rajesh Gopal, the veteran big cat expert who is also the chairman of 11-member Steering Committee set up by the Centre to monitor the ambitious cheetah relocation programme in the sub-continent.

Gopal’s confidence — for many years he headed the Project Tiger which was instrumental in saving the tiger from extinction — flies in the face of a large number of naysayers who have been dead against the cheetah relocation programme from day one. This vocal group loosely consist of amateur wildlife experts, photographers and coffee table book writers and others.

Human interface

During a long interaction with The Federal, Gopal underlined several reasons for his optimism. “First of all,” he argued, “there has been recorded evidence that cheetahs flourished in India for well over a thousand years. All those who maintain that India is not suitable for cheetahs do not know what they are talking about. Of course, one cannot compare Africa with India on geographical terms. And this is where the confusion lies.

Watch: Eighth cheetah dies | 4 questions on why cheetahs are dying in Kuno

“The human interface in India is unlike that of Africa. Here, we have different population dynamics in which tigers, leopards and all kind of wildlife has been surviving in close proximity to humans all these centuries. This is not the case in Africa. The geographical realities of two places are different. But to say that the African reality will hold sway over India’s, and therefore cheetahs here are fated to perish, is an erroneous belief. We have handled tigers and other big cats for decades. It all boils down to proper management of habitat as well as the human interface in and around the areas where cheetahs will live in India. We have done that with tigers. We will achieve same results with cheetahs too.’’

Space for cheetahs

Gopal also put to rest another argument brewing of late – that Kuno cannot hold more than 10 or 15 cheetahs without their indulging in fatal infighting. The area of Kuno is roughly 700 square km. But here lies the catch. According to Gopal, more than 6,000 square km of Kuno landscape will be available to the cheetahs, and this include, apart from the national park, the adjoining track of land such as Shivpuri, Greater Shivpuri and Greater Kuno. “This is an uninterrupted stretch which is 10 times more than the area earmarked for the present lot of cheetahs. To make the larger areas accessible to cheetahs, we have been holding meetings with the civil administration of the region,” he said.

On the question of some radio collared cheetahs getting wounds on their neck on account of the collars, and dying because of it, Gopal said this was an issue they were looking at on a priority. “We have sent the samples to the lab. If this is indeed the cause of their death, we will take remedial action.”

Bio-rhythm, homing instinct

Two other important factors, though not understood much by people at large but which are bound to play out with the cheetahs in India, relate to their altered biological rhythm and what is known in the scientific community as “site fidelity”.

Watch: The dark clouds over India’s cheetah project

Site fidelity, explains Gopal, is an exploratory force which plays a crucial role in the life of many animals and birds. In a layman’s language, site fidelity implies a tendency seen among mammals, birds and even fish to return to their original homes. This is often witnessed in domestic cats and even several species of birds who fly thousands of kilometers to lay eggs but after successful breeding return to their homes by the same route. At least for some time, the cheetahs in Kuno could face the pressure of site fidelity but would, sooner or later, accept their new home.

Also, adds Gopal, “there is this aspect of biological rhythm. In Africa, these cheetahs were existing alongside other predators such as lions, leopards, wild dogs and even different set of prey animals. In Kuno, not only the landscape but the predators and prey have altered for the new incumbents. So, they will need time to adjust to their new biological rhythm.’’

Time to settle

Unfortunately, these ancient realities and time-consuming processes which holds sway over a large part of animal kingdom will be difficult to fathom by most humans for whom instant results and immediate gratification remain paramount. It was to this new breed of restive crowd that John W Gardner had quipped half a century ago: “God is not a cosmic bellboy.”

Also read | Cheetah project has not failed, fence their habitat: South African expert

It is for these reasons, stresses Rajesh Gopal, that one should not expect the cheetahs to adopt to Indian conditions within weeks or months. “This will take much longer, perhaps many years before the cheetahs start accepting India as their new home. And in between there will be mishaps and casualties.

“Nobody escapes the rhythm of life and death. So why should cheetahs be immune from this truth? Sure, they will face competition for prey as well as threat from other hunters of the jungles, even from humans. That’s a given. Why, I once saw a group of feral dogs kill a beautiful snow leopard in Spiti. These are facts of life which we much accept,’’ he said.