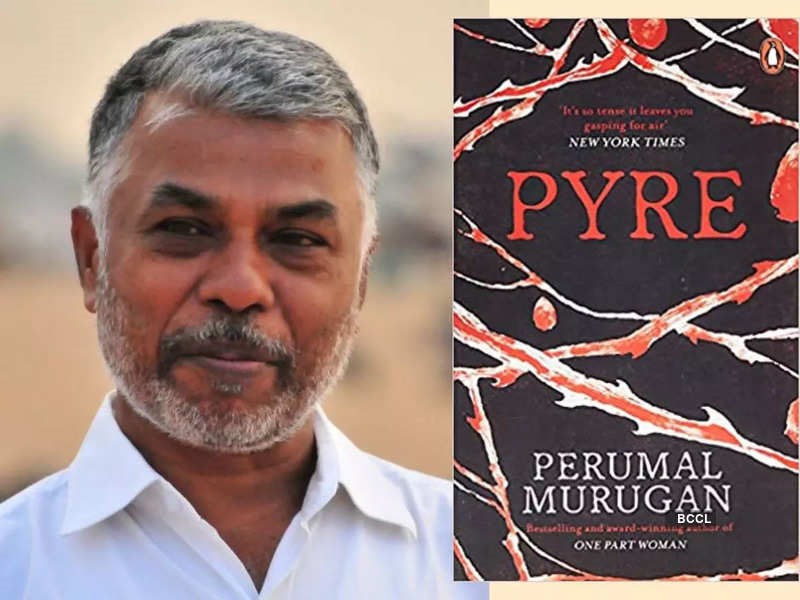

The arid, defiant world of International Booker-longlisted Tamil writer Perumal Murugan

Perumal Murugan’s characters inhabit an arid landscape. When the author, who has recently been longlisted for the International Booker Prize for Pyre (translated by Aniruddhan Vasudevan), takes us there in all his novels, he gives us the impression that there is no hope, only rocks, and miles and miles of nothing and bushes. We can see it as metaphor, we can see it as stark reality that a social realistic novel should have at its core.

It is a landscape that is as barren as the minds of people who inhabit those places. They live basic lives, but are totally controlled by social and religious myths. They stand opposed to modernity and are content to disregard the waves of modernity — the big towns, the fast buses, the things they make in big buildings in faraway towns. In Murugan’s landscape, they live another life. But they are aware of their caste, their colour , their religion, their rice gruel, their ignorance , the complexities of their tradition which they worship and cling on to. In the process, they deny themselves and often embrace darkness.

Taking women through life’s travails

“Beyond the tamarind trees that lined the road, all they could see were vast expanses of arid land. There were no houses anywhere in sight. With each searing gust of wind, the white summer heat spread over everything as if white saris had been flung across the sky. There was not a soul on the road. Even the birds were silent. Just an ashen dryness, singed by the heat, hung in the air. Saroja hesitated to venture into that inhospitable space.” This is how Murugan begins Pyre. We plunge straight into that arid land. Like Saroja, who is now confronted not just with her future with Kumaresan, with whom she has eloped and come straight to this arid hell. We can guess what awaits her.

Also read: Perumal Murugan’s Tamil novel ‘Pyre’ longlisted for International Booker Prize 2023

In fact, everything that a woman fears is lying in wait for her: Kumaresan’s mother who suspects she is from another caste since she is fair-skinned and constantly taunts her, the many suspicions of that villagers whose minds are as arid, the total hopelessness of everything that surrounds Saroja, who is so innocent and so full of love for this man, this useless soda maker who has neither any future nor any idea to go about it. But he, too, has sworn to look after her.

We know where Murugan’s empathy lies. His heroines have a quiet determination. In his debut novel, One Part Woman (2010), his heroine, the so-called infertile woman, goes in search of succour in a fantastic climatic upheaval. Here, too, the heroine is a masterly creation caught, as any Indian woman is, between the terrible trappings of convention and superstition and the urge to become a real woman. Murugan knows women like few Indian writers do and he holds their hand as he takes them through life’s travails.

Pastoral romance

In Poonachi , the name of the protagonist goat, it falls upon this cute domestic animal to reflect the pathos of poverty and struggle, again set in the arid lands of south Tamil Nadu. It is difficult to figure out if Poonachi is the real woman, suffering and looking on painlessly . “Poonachi was beset by acute hunger. She was constantly famished. The green fronds were not enough. She ate the bark off trees. With great effort, she chewed and swallowed sticks and twigs. She couldn’t even fill her belly with water. The old woman trudged to some distant place and came back carrying a pot of water. From the pot, she would measure out a little water and give it to Poonachi.” In Murugan’s world, water is the most precious; every drop helps to keep people afloat. Here it is the goat Poonachi. Goat and man are one. Both are helpless.

Also read: Writer’s eviction from Chennai Book Fair unacceptable: Perumal Murugan

Murugan’s novels also have the settings and contours of a pastoral romance. Here too, love, though furtive, holds sparks of light in the enveloping darkness. Like Kumaresan and Saroja, the main characters are deeply in love, often wondering what awaits them, but then summoning the courage that comes from within : “He looked at her face. A lock of hair had escaped her plait and swayed against her cheek. He longed to gently tuck it behind her ear.” This is how restrained and detached love can be in Murugan’s doomed villages.

Tragedy and foreboding

With Pyre, Murugan is again in familiar terrain where people live on the brink and though they are close to the intersection where one road leads them to the future, they all prefer the remoteness of their existence, the only contact with the world outside when they go stand in a queue to collect free rations like in Poonachi. The sense of tragedy and foreboding is present at every turn and Murugan is master of this art.

Murugan’s familiarity with tragedy and poverty is astounding. Often a drop of water or a pinch of salt to add to the rice gruel takes away a few sentences. Poonachi dies and turns into a stone idol. His women, too, are doomed to go that way. But in One Part Woman, she is defiant and, in a way, triumphant as during the booming drumbeats of the temple festival she moves away, and goes in search of the man who will impregnate her and, thus, finally get rid of that eternal shame of being infertile.

Murugan’s concerns are real, far away from the middle-class living room novels that are dime a dozen. Here, there is no wait for the visa to go to a bigger world and start counting the dollars. Here, they wait for raindrops to fall and the little green leaves to sprout so that their goats can eat. Perumal Murugan’s novels hold a mirror to our pathetic lives and our villages, rooted in the past. In that sense, he is the real Indian novelist.