‘The Bengal Files’ debate: Cinema, history, and responsibility

'The Bengal Files' trailer reignites debates on how cinema handles history; is it about bringing hidden truths to light, or is it a risky retelling that fuels old conflicts?

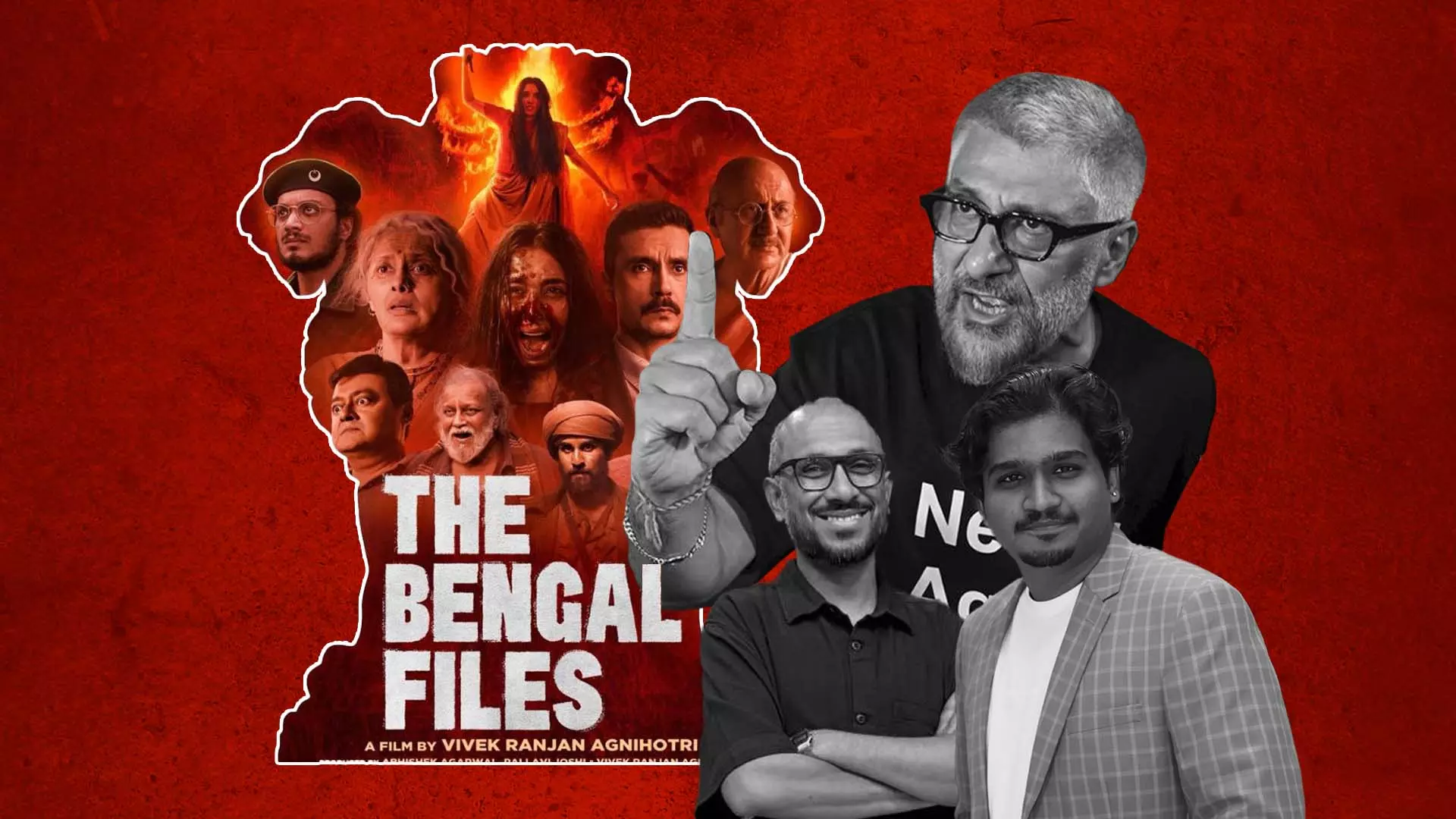

A storm has erupted over Vivek Agnihotri’s upcoming film The Bengal Files, with its trailer sparking heated debates and disruptions at launch events.

The film, claiming to portray forgotten truths of history, has already raised concerns about propaganda, accuracy, and representation.

In this conversation, author and film journalist Amborish Roychowdhury dissects the controversies, the responsibilities of filmmakers, and the role of audiences in engaging with such sensitive portrayals.

Even the trailer launch of The Bengal Files faced disruptions and hurdles. What does this tell you about the challenges filmmakers face while dealing with sensitive subjects?

Every film, however truthful or problematic, has a right to exist—just like every human being has a right to exist, whether good or bad. Films like The Bengal Files, Santosh, or Dibakar Banerjee’s Tees should have the right to be screened, and people should have the right to watch and decide for themselves.

But in India, too many elements interfere. Passions run high, and barriers emerge between a filmmaker and the audience, especially when the subject matter is considered controversial.

Also read: 'Kesari 2', 'The Bengal Files' under fire as TMC slams makers of both movies

Do films based on sensitive historical episodes act as reminders of forgotten truths, or do they end up re-triggering old conflicts?

In India, it’s often the latter. People here are extremely passionate and tend to react emotionally and aggressively to such subjects. Instead of detachment, which is needed to view a work of art as art, we see audiences being triggered.

This leads to anger and sometimes even actions against films. Unfortunately, our culture still lacks the detachment needed to examine history critically through cinema.

When portraying real-life characters on screen, how careful should filmmakers be in balancing fact and fiction?

It’s a very thin line. Cinema has always depicted real-life figures both accurately and inaccurately—sometimes for aesthetic reasons, sometimes for pushing an agenda. Quentin Tarantino’s portrayal of Hitler’s assassination is just one example.

But filmmakers should remain mindful of the impact their work may have. In India, the emphasis on research is alarmingly low. Too often, films prioritize passion or agenda over accuracy. History is rarely black and white, yet Indian cinema often reduces it to heroes and villains. The real challenge—and responsibility—is to depict the greys.

Also read: Award for Kerala Story: Kerala CM says it's an insult to Indian cinema's legacy

How can filmmakers maintain balance if they are inclined towards one side of history?

Striking a perfect balance is difficult. Every work of art is political—it reflects the creator’s worldview, upbringing, and biases. A fiction film also needs to entertain, which pushes filmmakers to dramatize or fictionalize characters, sometimes at the cost of accuracy.

The attempt should always be to get as close to the truth as possible. A visible effort to research and adhere to historical facts is essential, even if complete neutrality is impossible.

Vivek Agnihotri claims his characters are inspired by real people and reflect historical truth. Is that enough for historical storytelling?

Of course, a filmmaker will claim their work is factual. But the responsibility lies with the audience too. Cinema is like any purchase—you apply discretion before accepting it.

When a film claims to be based on history, viewers must do their own research, especially if it deals with episodes that caused mass suffering. Today, resources are widely available, and audiences should question whether a film is simplifying history, demonizing groups, or painting heroes and villains. History is never simple, and audiences must demonstrate discernment.

How important is it for actors to understand the historical and cultural context of films like this?

There is no one rule. Many actors play roles that are politically different from their personal beliefs. Nawazuddin Siddiqui, for instance, played Balasaheb Thackeray despite possibly not sharing his ideology, because he found the role compelling.

Actors often only know their portions of a script, not the full politics of the film. Some actors refuse roles that conflict with their values, while others embrace roles that are challenging, even if the film itself is problematic. It ultimately depends on the individual actor.

Also read: Kerala CM inaugurates Film Conclave, slams National Film Awards over Kerala Story

Agnihotri’s previous films have been called propaganda by critics, while others see them as truth-telling. How should audiences judge where a film really stands?

Audiences must develop the rigor to question whether a film is presenting history or pushing propaganda. It requires curiosity and research.

Propaganda itself is not always negative. Utpal Dutt, the legendary actor and playwright, openly called himself a propagandist because he used theatre to push the Leftist politics he believed in. On the other hand, Nazi propaganda was destructive.

Films like The Bengal Files have the right to exist, but audiences must ask why such a story is being told and whether it’s close to truth or designed to stir emotions for mass appeal.

Bengali cinema has historically reflected progressiveness and pluralism. Where does The Bengal Files fit into that tradition?

I haven’t seen the film, so I can only judge from the trailer and Agnihotri’s past work. The trailer shows troubling signs: fake Bengali accents, oversimplified depictions, and cardboard-like portrayals of figures like (Mohandas Karamchand) Gandhi and (Muhammad Ali) Jinnah. It doesn’t reflect deep research or nuance.

Bengal is too complex to be reduced to a single episode or simplified narrative. Its history includes poets, intellectuals, and filmmakers who navigated layers of politics and culture. To depict it in black and white strips away that richness.

Ritwik Ghatak’s cinema, for example, explored the tragedy of Partition with depth and humanity. That kind of engagement with truth is what defines responsible art. Entertainment cannot come at the cost of historical honesty.

(The content above has been generated using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.)