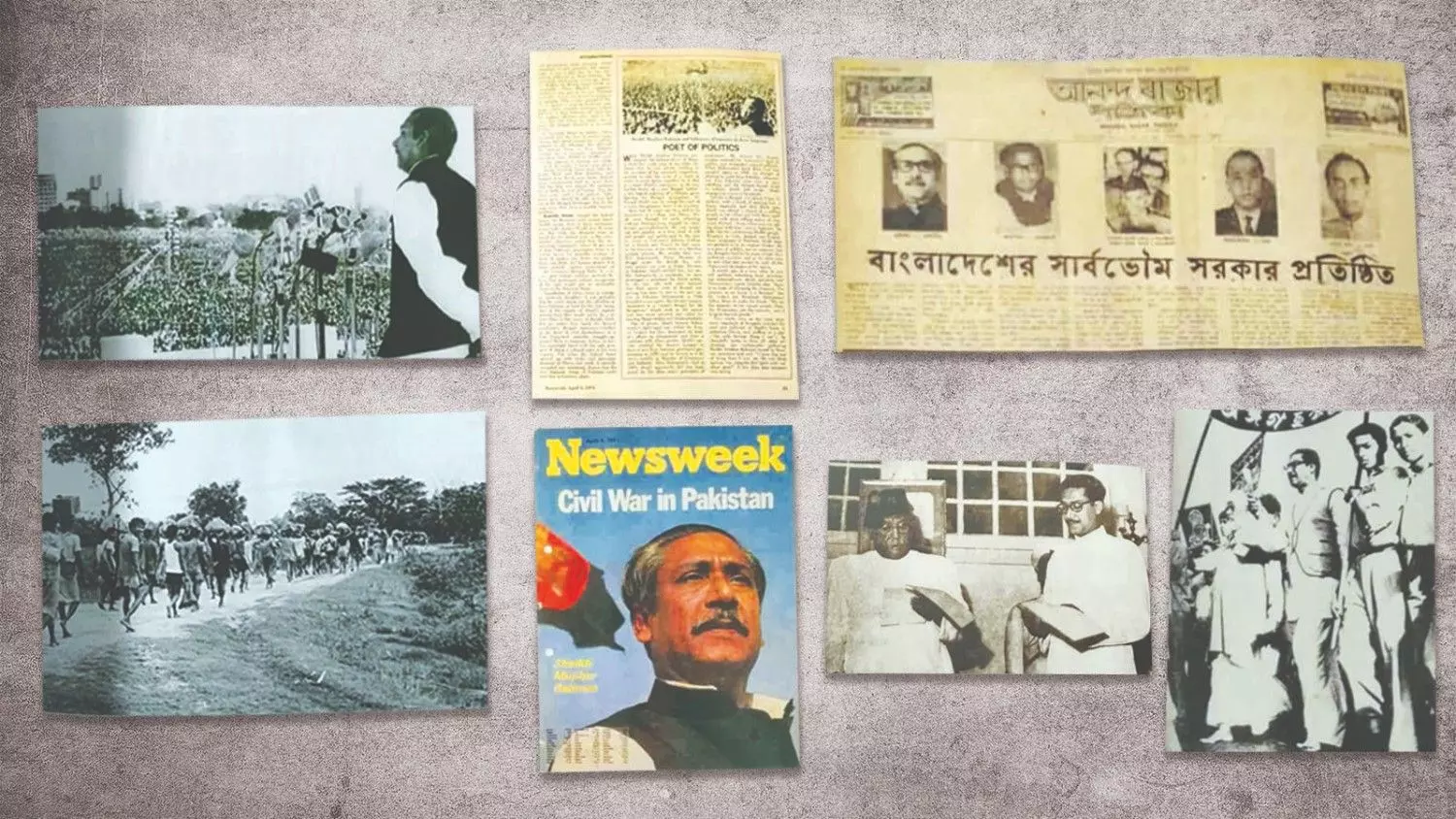

How Sheikh Mujib’s six-point charter became a clarion call for liberation

Mujib’s leadership and the Awami League's push for provincial autonomy paved the way for a secular Bengali nationalism and the eventual creation of Bangladesh. Second of a four-part series

On August 15, 1975, the newly forged nation of Bangladesh was shaken to its core. A coup d'état silenced the voice that had roared for Independence, and in the process, assassinated its architect, its father — Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

On the 50th anniversary of this dark day, here is the second of a four-part series exploring his life, enduring legacy, and his magnetic leadership. You can read the first part here.

The first part of this essay dealt with the history that we must keep in mind in order to understand how Sheikh Mujib ultimately became the icon of Bengali aspirations. If his own disillusion mirrored the disenchantment of Bengali Muslims in Pakistan, his uncompromising pursuit of a political solution would come to symbolise the Bengali search for liberation.

A household name

Already in 1949, Mujib was well known for his tireless interrogation of government policies, and his great personal charisma was quickly making him a household name, especially in his own district, Faridpur. As a rabble-rouser, he was a natural.

At a rally in Dhaka’s Armanitola Maidan held on October 11, 1949 — when Prime Minister Ali was in the city — Mujib spoke of the prevailing food crisis.

Also read: What China-Bangladesh-Pakistan trilateral mechanism means for India

“What should be the punishment of a murderer?” he thundered at the crowd. “Hang him!” the crowd roared back. “And what about those who cause the deaths of thousands of people?” he asked again. “Hang them too!” came the response. “No! They should be shot!” he flung back. “Come, walk with us, let us show Liaquat Ali what the people of East Bengal want.”1

The Mujib of later years was much more nuanced, sophisticated, and politically correct as well as imaginative in his interactions with the masses, without losing his earthy chemistry with the people. His politics was qualitatively different from that of his mentor, Suhrawardy, whose backroom compromises with elitist politicians in West Pakistan did not always serve the interests of East Bengal.

Mujib of the later years was much more nuanced, sophisticated, and politically correct as well as imaginative in his interactions with the masses, without losing his earthy chemistry with the people

For all Mujib’s unwavering affection for Suhrawardy, for most of his life, his own politics had the people at its centre.

As early as the late 1940s, Mujib and his Awami League colleagues combined the demand for provincial autonomy with the demand for democracy. A democratic transition, they believed, was possible only if East Bengal had provincial autonomy; the first Awami League manifesto included this demand.

Also read: Bangladesh to hold general elections in February 2026 amid rising voter apathy

The 1952 language movement, which identified language rather than religion as a marker of nationhood, prepared the ground for the secular Bengali nationalism that Mujib and the Awami League came to represent.

Mujib, with his infallible finger on the pulse of the people, knew when the time was ripe to strike. Suhrawardy’s passing in December 1963 may have been personally devastating for him, but it had also freed him from the restraining influence of his moderate mentor.

In 1949, the new party was not confident enough to announce its secular character. It took another few years for the party to shed “Muslim” from its name, in late 1955.2

As the 1950s progressed, however, and certainly in the 1960s, secular Bengali nationalism became practically identified with the demand for democracy and provincial autonomy.

Denial of democracy

The provincial assembly election of 1954 showed the ascendancy of opposition politics in East Bengal. The Muslim League was all but wiped out — with just nine seats in the new assembly of 309 members. The opposition coalition, United Front, won 223 seats, with the Awami League alone securing 140.

The central government in Karachi, however, invented one pretext after another to subvert the democratic process. Consequently, Mujib and the Awami League were soon back in their opposition role, until General Ayub Khan seized power in October 1958 and political activity became banned in Pakistan for the next four years.

Also read: Bangladesh after Sheikh Hasina: What India has failed to see

This enforced hiatus in active politics turned out to be a crucial time for the Bangladesh movement. In the early Sixties, the disparity in the allocation of resources between the eastern and western zones of Pakistan began to feature in the work of prominent economists in Dhaka — Dr A Sadeque, Dr Nurul Islam, Dr Habibur Rahman, Dr Akhlaqur Rahman, Dr Mosharaff Hossain, Abdur Razzaq, Professor M N Huda, Professor A F A Hossain, and Rehman Sobhan.

Some of them, such as Sobhan, even talked about the need for land reforms (much to the chagrin of the landed oligarchy in West Pakistan), and worse, expressed opinion in favour of provincial autonomy as the only solution to the problem of unequal resource allocation. These economists were hardly very vocal outside the academia. Most of them, unwilling to attract frowns from the ruling junta, preferred to confine their views to academic papers that remained within university circles.

But this was also the time when politicians like Sheikh Mujib3, with enough time on their hands because political activity was prohibited, started interacting with some of them. The economists’ work lent intellectual grist to their ideological mill4.

Until 1969, the Pakistani establishment paid scant attention to the economists’ complaints about unequal allocations and chose to treat critical views expressed by Bengali economists as politically motivated. When policymakers in West Pakistan finally woke up to the problem, it was too late.

Mujib’s Six Points: Blueprint for autonomy

Under Mujib’s leadership in the 1960s, the Awami League’s commitment to provincial self-rule became forcefully linked to a socialist vision. His negotiations with the central government (and with West Pakistani politicians), whether during Ayub’s time or Yahya Khan’s and right up to the last days before the fateful night of March 25, 1971, were always backed up by the meticulous work of a team of economists.

Also read: Awami League resistance turns deadly as Bangladesh govt’s political push falters

Scholars such as Nurul Islam and Sobhan lent their services to the party to build a case for the feasibility of provincial autonomy and the socialist economy that this would facilitate.

The charade of democracy5 that marked the Ayub years, combined with the hardships that followed the 1965 war with India, created disquiet in both wings of Pakistan. In East Bengal, especially, war-induced feelings of isolation and insecurity sharpened aspirations for autonomy.

Mujib, with his infallible finger on the pulse of the people, knew when the time was ripe to strike. Suhrawardy’s passing in December 1963 may have been personally devastating for him, but it had also freed him from the restraining influence of his moderate mentor.

In 19666, Mujib came into his own as a visionary politician with his Six-Point Charter of demands7, called “Chhoi [six] dapha” in Bengali, which presented a paradigm for provincial autonomy.

When Mujib tabled the charter at a convention of opposition leaders in Lahore in February 1966, West Pakistan politicians were not impressed. Not all politicians in the province were sympathetic, either. Maulana Bhasani8, whose political somersaults eventually marked him out as an absurd figure though he never completely lost his personal popularity, even called it a “CIA document”.

But the Six-Point Charter struck an instant chord with the people of East Pakistan. A leaflet explaining the demands was circulated, and Mujib himself was once again tearing around the province like an irresistible hurricane, with law-enforcers in hot pursuit. In the first three months of the campaign, he was arrested eight times after holding rallies in Dhaka, Chittagong, Jessore, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Khulna, Pabna, and Faridpur9.

On the midnight of May 8, he was arrested in Dhaka following a rally in Narayanganj. It was a long haul this time. Mujib would come out again only on February 22, 1969. Other Awami League leaders, including Mujib’s right-hand man Tajuddin Ahmad, were also locked up.

The military dictatorship ruled by force rather than consensus. If it condescended to allow a dialogue on provincial autonomy, which was what the Six Points were about, was it not but a short step from countenancing outright secession? This wariness about allowing self-rule in a province that was refusing to be treated like a colony anymore was what would ultimately split Pakistan.

What Six Points meant for Bengalis

But what did the campaign mean to the ordinary people of East Pakistan? What did it mean for its beleaguered Hindu minority? Perhaps it will not be amiss to look at the testimony left by the poet Nirmalendu Goon in his third book of memoirs, Atmakatha Ekattor (My Story, ’71).

In 1966, Goon was 21, studying for his B.Sc. degree at Mymensingh’s Anandamohan College. The communal riots of 1964 had prevented him from securing admission in Dhaka University’s newly opened pharmacy department despite having cleared the entrance test.

In 1965, he cleared the admission test of East Pakistan University of Engineering and Technology10 but failed the viva. He had let it slip during the oral interview that he had an elder brother in India and believed that this why he was denied admission. “What if I left for India after passing out? India was then the newly announced enemy state, and the Hindus of East Bengal were Pakistan’s unannounced enemies.”

The Six Points made sense to him as a way out of the senseless prison of denied opportunities that East Pakistan now felt like to the young poet.

On June 7, 1966, the people of East Pakistan responded as one to a call for a general strike by the Awami League to demand the release of Sheikh Mujib and other party leaders. In Dhaka, there were casualties when the police fired at peaceful demonstrations.

The arrests were indiscriminate: close to a thousand people were picked up from the streets, including people going about their daily business11. That evening, Goon watched a train from Dhaka chugging into the Mymensingh station.

It was practically empty, pointing to how successful the day’s strike had been. The emptiness of the bogies carried the silent scream of people who had had enough.

“Looking inside that passenger-less train, I could see the Bangladesh of the future,” Goon wrote. Back in the Anandamohan College hostel that night, he wrote his first poem on Sheikh Mujib and his Six Points — “For a Golden Rose”.

“Not all huddled up like a patient on a winter’s night,

But fearless like the fiery people of the town.

Nothing fearsome about the colour of blood,

All you free people of a free country, rejoice.”12

The empty train held for the young poet the vision of a country where he would not have to be at a disadvantage because of his religion. Half of his family had by this time migrated to India, and some of the departures were traumatising.

He and his parents had stayed back. In an autonomous East Bengal, under a leader like Mujib, perhaps he would never be forced to leave. Perhaps, too, he would be free to become what he wanted.

The Six Points brought a whiff of freedom to a repressed people. Collectively, and for the individual, it meant the promise of more control over destiny.

Popular uprising in 1969

By December 1968, the wind blowing in that whiff had grown into a storm. East Pakistan politics in those heady days of December 1968 and the first two months of 1969 was heavily influenced by student activism in Dhaka. The Dhaka University Central Students Union (DUCSU) set up the All-Party Chhatra Sangram Parishad in December. This left-leaning group’s 11-point demand charter (Egaro Dapha) included Mujib’s Six Points and projected the vision of a socialist state.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, the National Students Front (NSF), a student organisation that had been nurtured by Governor Abdul Monem Khan13 to counter forces sympathetic to the Awami League on college campuses, pitched its tent with the Chhatra Sangram Parishad at this time.

There seemed to be a rare unity among political parties too. Eight political parties of the province — including Awami League, Council Muslim League, Pakistan Democratic Party, National Awami Party, Jamaat — came together on a common platform, Democratic Action Committee (DAC), to press for restoration of democracy.

Ayub Khan could feel his throne wobbling.

The strategy of dumping Awami League leaders in jail had backfired. Mujib’s incarceration, in particular, made him a hero in people’s eyes — especially his detention in the Kurmitola Cantonment from January 1968 under charges filed against him in the Agartala Conspiracy Case14.

All newspapers in East Pakistan, including the ones dedicated to the “official” views, published detailed daily reports of the depositions of the accused during their trial by a special tribunal.

The expectation probably was that these reports would turn public opinion against Mujib. In reality, these provided the jailed leader an excellent opportunity to get his voice across to the public.

In Goon’s description, Mujib’s deposition was “well-written, well-thought-out and emotive”. When he finished deposing, the crowd gathered at the cantonment to watch the proceedings started cheering for him.15

Dhaka exploded in the first two months of 1969. Two decades of economic deprivation, denial of democracy, repression of dissent, and efforts to choke the cultural freedom of a people aware and proud of its heritage had created a pressure-cooker situation that could no longer be contained.

For many years, dissent had been kept alive by cultural activists like Sufia Kamal, Sanjida Khatun, and Wahidul Huq, and found poetic expression in the work of writers such as Shamsur Rahman. The mid-1960s had a bunch of angry young poets (including Goon) whose lifestyle as well as their poetry challenged many established notions and showed a healthy disregard for authority.

Liberal arts departments in the universities of Dhaka and Rajshahi16 had moulded generations of students to question and argue. Dissent informed a conscious nurturing of Bengali language and literature and refusal to junk “Hindu” literary giants such as Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore, in fact, became an icon of resistance in the face of the regime’s repeated and pig-headed attempts to erase his legacy.

Bengalis in East Pakistan had shown the world that dissent need not only be about protests and politics. Bengali dissent had turned itself into a cultural efflorescence through Bengali New Year (pahela baishakh) festivities, celebrations of Tagore’s birth anniversary, the staging of plays and poetry-reading sessions, and of course, the February 21 programmes every year.

Bengali dissent had turned itself into a cultural efflorescence through Bengali New Year festivities and celebrations like Tagore’s birth anniversary.

Visually, the most joyous expression of Bengali dissent perhaps consisted in the resplendent alpana (floor drawings with rice flour or any coloured powder) that covered the main streets of Dhaka on these occasions, a tradition that still endures.

But now it was time for a conflagration. People pouring into the streets in January-February 1969 thought nothing of defying curfews, refused to be cowed down by bullets, and vented their fury by burning symbols of authority—residences of ministers and judges and offices of pro-government newspapers.

Publicly held namaze janaja (funeral prayers) for those killed during the agitation were attended by lakhs of people, and huge public rallies called for the unconditional release of Sheikh Mujib and other political prisoners.

When Ayub Khan, increasingly on the edge, called for talks with opposition leaders, the Chhatra Sangram Parishad warned DAC leaders not to start a dialogue with any of the leaders in jail. In the end, the government was forced to release all political prisoners and fold up the Agartala Conspiracy Case.

Charges against Mujib were dropped. On February 22, 1969, he walked out of the Kurmitola Cantonment, but not before making sure that all others charged in the case were also freed. He was the last to step out into freedom.

Mujib’s speech after release

The next day, Mujib spoke at a public meeting convened by the Chhatra Sangram Parishad in the Ramna Racecourse. The historic March 7 speech in 1971, counted among the best political speeches in the world, was delivered in a moment of extreme tension when the future of Bangladesh hung in balance.

But February 23 in 1969 marked a moment of pure exhilaration. The people had made the military regime bend to its wishes, and Dhaka could take stock of the gains of the past two months of agitation. The promise of freedom was in the air.

In that meeting, attended by 10 lakh people according to Goon, Mujib received the title of “Bangabandhu” — proposed by student leader Tofael Ahmed and endorsed with thunderous applause from the crowd.

Goon was at the Ramna Kali Temple17 with another young poet that day and had arrived early enough to watch the huge empty field fill up with people. It was he would later write, like looking at floodwaters rushing in.

When Mujib stood up to speak, he declared his resolve to keep fighting to secure the rights of Bengalis. But he also joked, shared anecdotes18, told stories, made people laugh, and asserted East Bengal’s right to hold Tagore close to its heart.

To read Goon’s account of that speech is to be reminded that humour, rather than bluster, is the mark of a great leader. Listening to Mujib’s witty jibes making laughingstock of the figures of authority that had ruled with an iron fist for so long must have been a liberating experience for his audience. To be able to laugh at the bully who expects deference is to lose fear.

With the crowd listening in pin-drop silence, Mujib told, too, the story of how he was taken out of Dhaka Central Jail one cold January night in 1968, to be rearrested at the jail gate in the Agartala case. Perhaps the truly unafraid do not hesitate to talk about their vulnerabilities.

Mujib, who in 1971 would respond to threats of hanging in his West Pakistan prison with the request that his body should be buried in Bangladesh, told the gathering how that night his heart sank in apprehension and how he stooped to scoop up a handful of mud and rubbed it, the soil of Bengal, on his forehead and recited a favourite line from D L Roy’s song: Amar ei deshetei jonmo/ jeno ei deshetei mori (In this land of my birth/May I breathe my last).

To a poet, albeit one who was a lifelong and blind admirer of Mujib, the narration sounded like a lover whispering a piteous tale into the ears of his beloved.19 Mujib and his listeners were bound by a common idiom.

The next part will trace the historical process that ensured that the Bengalis of East Pakistan already believed themselves to be a free nation when the tanks rolled out of the military cantonments on the night of March 25, 1971.

ENDNOTES

1 Asamapto Atmajeeboni, page 132. Badruddin Umar, who was no admirer of Mujib’s, has recorded, in his book on the language movement, a somewhat differently worded account of this call to action.

2 Progressive politicians within the Muslim League had tried to assert the need for secularism as a political goal immediately after Partition, but such moves could not make much headway then.

3 Mujib, too hot to handle for the junta, was kept behind bars for over two years, from October 12, 1958, to December 7, 1960. But he made good use of his time once he was out.

4 Ahead of the historic election of 1970, the content of the legendary poster on the east-west disparity — Sonar Bangla Samsan Keno (a not very literal translation would be “why golden Bengal is brought to its knees”) — was based on the work of Nurul Islam. “Sonar Bangla Samsan Keno” also became a popular slogan.

The poster of the historic 1970 general election in Pakistan which was swept by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's Awami League. It was prepared by Janab Nurul Islam and drawn by artist Hashem Khan.

5 Field Marshal Ayub Khan’s absurd “basic democracy” with its system of indirect elections that followed the first four years of prohibition on political activity fooled no one.

6 In January 1966, Mujib was elected the president of the Awami League and Tajuddin its general secretary.

7 The Six Points were:

1) The Constitution should provide for a Federation of Pakistan in its true sense based on the Lahore Resolution, and the parliamentary form of government with supremacy of a Legislature directly elected on the basis of universal adult franchise.

2) The federal government should deal with only two subjects: Defence and Foreign Affairs, and all other residual subjects should be vested in the federating states.

3) Two separate, but freely convertible currencies for two wings should be introduced; or if this is not feasible, there should be one currency for the whole country, but effective constitutional provisions should be introduced to stop the flight of capital from East to West Pakistan. Furthermore, a separate banking reserve should be established and separate fiscal and monetary policy be adopted for East Pakistan.

4) The power of taxation and revenue collection should be vested in the federating units and the federal centre would have no such power. The federation would be entitled to a share in the state taxes to meet its expenditures.

5) There should be two separate accounts for the foreign exchange earnings of the two wings; the foreign exchange requirements of the federal government should be met by the two wings equally or in a ratio to be fixed; indigenous products should move free of duty between the two wings, and the constitution should empower the units to establish trade links with foreign countries.

6) East Pakistan should have a separate military or paramilitary force, and Navy headquarters should be in East Pakistan.

8 Maulana Bhasani left the Awami League in 1957 to form the National Awami Party, or NAP

9 See Sheikh Hasina’s Introduction to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Karagaarer Rojnamcha (Prison Diaries), Bangla Academy, Dhaka, 2017.

10 Now called BUET, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology.

11 The information of the approximate number of arrests is from Sheikh Sadi’s biography of Sheikh Mujib, Bangabandhu Purno Jibon, Kathaprokash, Dhaka, 2015.

12 Translated by author.

13 Monem Khan was Governor of East Bengal from 1962 to 1969. He fled Dhaka in 1969 following Mujib’s release, anticipating public fury.

14 A sedition case in which Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and some serving and retired army officers and government officials were accused of hatching a conspiracy to detach the eastern wing from Pakistan with India’s help.

15 Nirmalendu Goon, Amar Kanthaswar (My Voice), Kathaprokash, Dhaka, February 2013. Page 265

16 See Sanat Saha’s essay “Teacher and student in the same bunker” in the collection essays Bangladesher Muktijuddha (Liberation War of Bangladesh), University Press Ltd., Dhaka, 2009 for a discussion on the role of the two universities in the Bangladesh’s struggle for liberation and his recent book Rajshahi Bishwabidyalayer Saat Dashok (Seven Decades of Rajshahi University, Kathaprokash, Dhaka, 2023.

17 This historic 400-year-old temple located inside the Ramna racecourse was destroyed by Pakistani soldiers in 1971.

18 Among the stories he told that day was one about how Governor Monem Khan had remonstrated with Professor Abdul Hai, Dhaka University’s legendary professor of Bengali, about the unnecessary fuss intellectuals made about Tagore songs. Why not write Rabindrasangeet yourself, the Governor is said to have told the bemused teacher. I can, Prof. Hai apparently said, only it won’t solve the problem, because it won’t be Rabindrasangeet, it will be “high sangeet”.

19 Amar Kanthaswar, page 356.