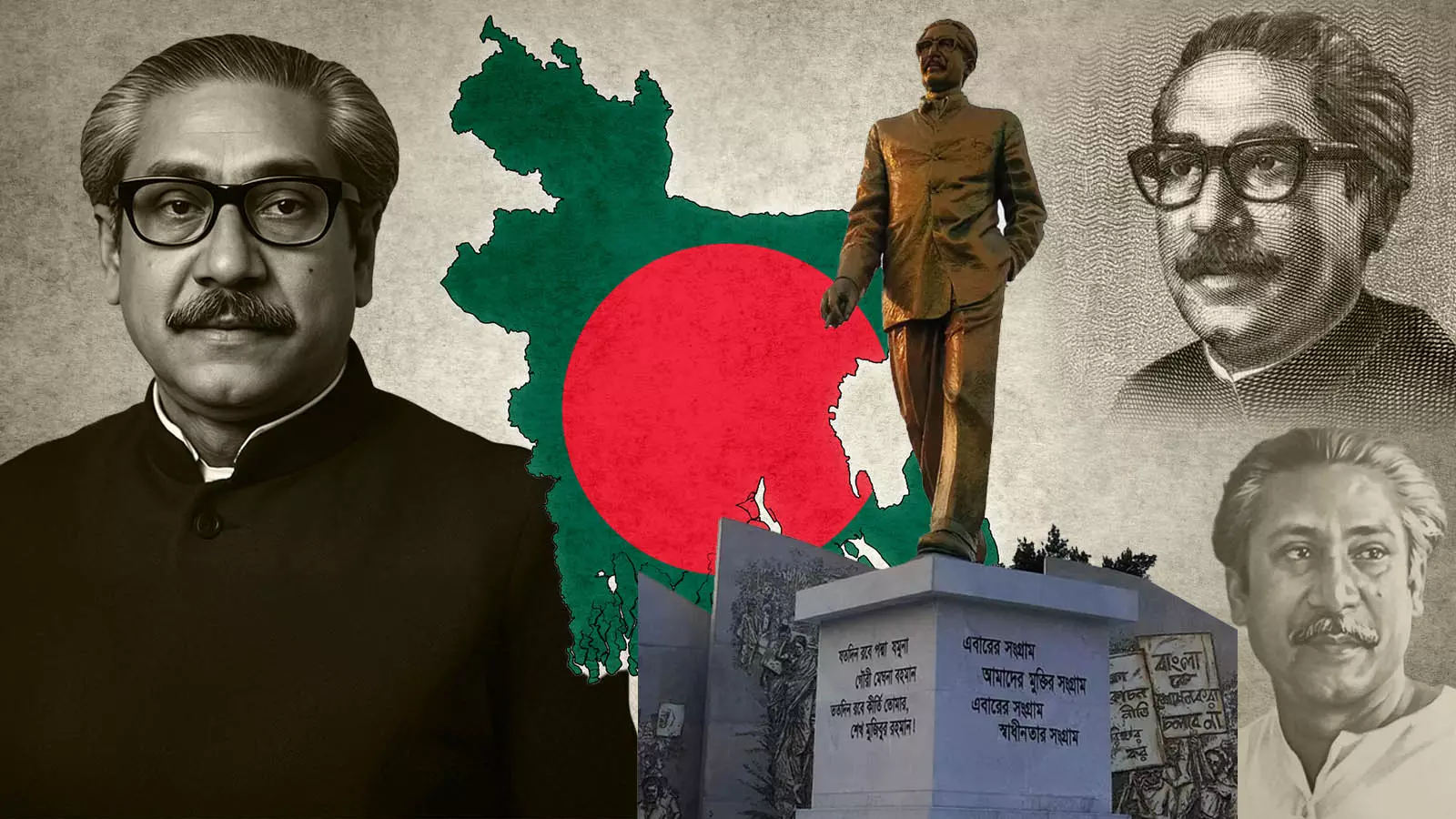

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman: Not a mahatma but a bandhu

The history of the Bengali Muslim’s search for identity is the history of Bangladesh. It is also the story of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s life. First of a four-part series

On August 15, 1975, the newly forged nation of Bangladesh was shaken to its core. A coup d'état silenced the voice that had roared for Independence, and in the process, assassinated its architect, its father — Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

As we mark the 50th anniversary of the dark day, we begin a four-part series to explore his life, enduring legacy, and his charismatic leadership.

August 15, 2025, marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. For many Bengalis in Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujib is “Bangabandhu” (friend of the Bengalis), the icon of Bangladesh’s war of liberation. The emergence of free Bangladesh in 1971 was one the most spectacular and heart-warming events of the 20th century.

It capped nearly 10 months of resistance and covert counter-offensives by a tiny nation of seven crore people against the Pakistani establishment’s genocidal pogrom, which was carried out in the name of national integrity with moral and logistical support from the United States.

Also read: Bangladesh to hold general elections in February 2026 amid rising voter apathy

The world watched with incredulous admiration as the Bengalis of Bangladesh took control of their destiny at the cost of three million lives and unspeakable suffering endured by those who survived.

Rahman's radio message

For the entire duration of that war, Sheikh Mujib was incarcerated in West Pakistan. He was arrested from his Dhaka home on the night of March 25-26, 1971, but not before he sent out a radio message declaring Bangladesh was a free nation. When he came back on January 10, 1972, via London and Delhi, it was to a liberated Bangladesh.

Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali said Urdu was the only language that could keep the people of the eastern and western zones “jointed together”. The response from the student community in Dhaka was instant and sharp.

One doesn’t know what the future holds, but Bangladesh, which is reinventing itself by dropping references to Sheikh Mujib as the “father of the nation”, and where even his grave does not seem safe from threats of violation, still celebrates March 26 as its independence day.

If the nation is an imagined entity, designating a leader as its “father” is an invention that provides a focal point for the values that breathe life into that ideological construct. In the process, it also makes an icon of that leader. A nation usually has very real and physical arrangements to protect its existence. The destructive power of the armed forces of modern nation-states makes it easy to forget that the “nation” is a human construct. To threaten a nation’s existence is to face its army.

Also read: Awami League resistance turns deadly as Bangladesh govt’s political push falters

Not so in the case of a “father of the nation”. It is far easier to imagine a “father of the nation” out of existence once the values symbolised by such a figure are forced to retreat. That is what appears to be happening to the once-iconic status of Sheikh Mujib in Bangladesh.

On the 50th anniversary of his death, this essay attempts to understand what had once elevated him to that status, and it will do so by reflecting on certain key moments of his life, moments that were transformative in the life of Bangladesh.

The birth of Bangladesh held a promise — of economic emancipation of a long-suffering people and the defeat of fanaticism. It was a proud moment for secular Bengali nationalism. In the years immediately following the liberation, however, that promise lay shattered as Bangladesh descended into a spiral of violence, chaos, terror attacks, soaring inflation, and unemployment, beset by natural disasters and famine, and gripped by despair.

“Bangabandhu” began to lose control, and his socialist economic programme bred anxieties in the short run that were sharpened by the way armed groups went about subverting the rule of law. Then came the assassination, wiping out Mujib and his entire family (except his two daughters, who were in Germany) and setting the clock backwards in the now “Islamic”1 republic of Bangladesh. Events since then have shown that the Pakistan years have left wounds that never quite healed and put down roots too deep to pull up completely.

The wait for Pakistan

Coming back to Mujib, it is sobering to remember how his own life mirrored the life of the country that he was in the habit of calling “Bangladesh” long before Bangladesh became a sovereign nation. To understand how that happened, we must take up the story from the decade when East Bengal’s Muslim majority eagerly waited for Pakistan — the 1940s — and even perhaps look a little further into India’s past.

Also read: Why should Sheikh Hasina submit to a sham tribunal in Bangladesh?

A Muslim homeland, it was hoped, would allow Bengal’s Muslim majority to come into its own as a nation, through economic emancipation and a sociocultural revolution that would give dignity to Muslim lives.

In a province where divisions between the landowning class and small tenants/landless peasants overlapped fault lines of religion and caste — where landowners were mainly upper-caste Hindus while Muslims and lower-caste Hindus made up the bulk of small tenants and landless peasants — the emergence of such aspirations was a matter of finding the right historical juncture. In other words, it was inevitable at some point.

Also read: Ex-Bangladesh PM Hasina indicted in crimes against humanity case

What lent the force of repressed steam to this aspiration, at least in the countryside, was the ecosystem of social exclusions and ritual barriers that the landowning Hindu upper castes had nursed over many generations. For young political activists such as Sheikh Mujib who reposed faith in the Muslim League to bring about a transformation, the condition of Muslim peasants and labourers was what they particularly hoped would change in Pakistan.

In August 1947, the politically conscious Muslim majority of East Bengal 2 expected to reap the harvest of the movement for Pakistan. It was this population that had provided the ballast for the Muslim League’s campaign for Pakistan in undivided India. (It was not a coincidence that both the Lahore Resolution of 1940 calling for a Muslim homeland and the 1946 resolution calling for Pakistan at the Muslim League convention of elected legislators in Delhi were moved by politicians from Bengal — A K Fazlul Huq and Hossein Shaheed Suhrawardy, respectively.)

With Pakistan attained in 1947, Dhaka throbbed with political excitement about what the future was going to hold. The city of Sheikh Mujib’s own political apprenticeship was Calcutta, where he had established himself from the early 1940s as a committed, articulate, and popular student leader of the Muslim Chhatra League and a protégé of Suhrawardy in the Muslim League. Although his roots were in East Bengal,3 Dhaka became his arena of political activity only after Partition. It turned out to be no less politically stimulating than Calcutta.

Delayed rise of Muslim middle class

In the fraught history of colonial Bengal, a literate Muslim middle class was slower to emerge than its Hindu counterpart. The colonial administration in the 19th century actively nurtured not only the growth of an educated Hindu middle class with a working knowledge of English, but also the development of the modern Bengali prose that educated Hindus were quick to own and convert, with spectacular success, into a vehicle of literature.

Muslims, suspicious of the entire exercise, chose to stay away from the new education system. When the tide started to turn at the end of the 19th century, education fostered a radical political consciousness among the Bengali Muslims and a new awareness of an identity that set them apart from Bengali Hindus.

The establishment of Dhaka University in 1921 was a compensatory move against the revocation of the 1905 partition of Bengal, which the majority of Bengali Muslims from East Bengal had eventually welcomed.4

Many young people in this age of super-expensive private universities that offer higher education as a commodity might find it hard to fathom, but universities have traditionally served as spaces where young people learn to think, question, and argue, challenge old ideas, and nurse value systems that nourish society.

Dhaka University, which was East Bengal’s only university at the time of Partition5, played a crucial role in the nurturing of an educated Bengali Muslim middle class and the emergence of a Bengali intelligentsia in the early 20th century.

Also read: Former Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina sentenced to 6 months in prison: Report

So did the “emancipation of intellect” movement (Buddhir Mukti Andolon) in the 1920s and 1930s in Dhaka.6 Notwithstanding eminent exceptions like Qazi Abdul Odud, many of the participants of this rational humanist movement had no hesitation in proudly asserting their Muslim identities.

Identity is, however, never static. Multiple identities can be embraced at the same time, and equally, one identity can be prioritised over another and alternatively, subordinated to or even rejected in favour of another. The history of the Bengali Muslim’s search for identity is the history of Bangladesh.

It is also the story of Sheikh Mujib’s life.

Bengal Pact: An unrealised promise

Chittaranjan Das’s 1923 Bengal Pact had been a visionary attempt at building an understanding between the two communities in Muslim-majority Bengal on the basis of a distribution of power/resources that would reflect the province’s demographic reality.

The pact mandated that 55 per cent of government jobs in Bengal would be reserved for Muslims, with 80 per cent of fresh appointments going to Muslims until the 55 per cent target was reached. It also accorded 60 per cent representation in local bodies to the majority community, that is, the Muslims.

Notwithstanding its rejection by the Congress7 , Das tried to hold on to the pact, knowing how important it was for a province where Muslims were an increasingly assertive majority with a newly awakened middle class and yet lagged behind the Hindus in education, employment, and political representation.

But Das died in June 1925, at a time when his protégé and supporter Subhas Chandra Bose was incarcerated in Burma. Hindu-Muslim animosities were rising all over north India during this decade, and the pact quickly became history.

The fight for Muslim identity

The distrust that now grew between the communities meant that by the 1940s, the politically aware Bengali Muslims, eager to find their place in the sun, found it expedient to prioritise their Muslim identity in their thoughts about a future homeland. In the radicalised political atmosphere of this tumultuous decade, Dhaka had a bunch of liberal, progressive political activists who, like Sheikh Mujib, were passionately invested in the idea of Pakistan.

So, when Mujib arrived in Dhaka8 in 1947, he walked into a fellowship of like-minded young men — Tajuddin Ahmad9, Shamsuddin Ahmad, Shamsul Haq, Abul Mansoor Ahmad, Shaukat Ali, Mohammad Toaha, and Oli Ahad, to name a few.

They did not always stay together on the same political platform in later years, but in the 1940s, they formed an assertive group with a secular and socialist worldview within the Muslim League.

Like Mujib, this group had supported the candidature of the liberal Abul Hashim10 as the Bengal Provincial Muslim League general secretary in 1944 against the influential and reactionary candidate propped up by the Nawabs of Dhaka. Hashim had won.

A certain vision of what Pakistan ought to be like held these men together in those volatile days of their youth. In his unfinished autobiography (Asamapto Atmajeeboni11), Sheikh Mujib recorded the fervour that animated his student years:

“I had started immersively engaging in political activities. Holding meetings, giving speeches. All the time it was only Muslim League, and Chhatra League. Pakistan had to be achieved, nothing else could save the Muslims. Whatever the newspaper Azad12 wrote appeared true to me.”13

Indeed, to read this book is to follow a young Mujib rushing around Bengal like a whirlwind in pursuit of a political vision. Pakistan would be the new homeland where Bengali Muslims would lead productive lives with dignity and in a peaceable coexistence with their Hindu counterparts.

Pakistan, Hashim told young Muslim Leaguers in Calcutta before 1947, was not meant to separate Hindus and Muslims but to enable them to live as brothers. The Muslim League, he told them, would have to be “rescued from the grip of reactionary forces” and brought out of the “pockets of landlords”.14

Bengali aspirations versus League plans

On the eve of Partition, progressive Muslim Leaguers in East Bengal had thoughts on the status that Bengalis should enjoy in the new nation and the socioeconomic path they should follow. The Partition Plan was announced on June 3. In July, a small leftist group within the League, calling itself the Gana Azadi League (People’s Freedom League), came out with a manifesto that said political freedom would be meaningless without economic emancipation, which alone could ensure social and cultural progress.

It also said, among other things, that Bengali would be the state language of East Pakistan, that the mother language (matri bhasha) should be the medium of instruction and “Bengali is our mother language”.

The leftist scholar-politician Badruddin Umar, who cited this manifesto in his seminal three-volume work Purba Banglar Bhasha Andolan O Tatkalin Rajneeti (East Bengal’s Language Movement and Contemporary Politics, published by Baatighar, Dhaka), also noted that this manifesto concerned itself only with East Bengal. The first-person plural pronoun “our” was only for the Bengalis. Already, before August 1947, there were Bengali politicians who expected their province to be autonomous. Presumably, in their vision, East Bengal would be bound in a loose federation with Pakistan.

Pakistan's geopolitical absurdity

Unfortunately, the Muslim League clique that seized power in Pakistan in 1947 did not share this vision. The new nation had to grapple with a geopolitical absurdity from the moment of its inception — its two wings were separated by about 1,600 kilometres of Indian territory. Constructing an Islamic identity and denying civilisational ties linking Pakistanis to their “Indian” past seemed to be the logical way of preserving territorial integrity. The first blow was struck on language.

Attack on language

On February 25, 1948, the Congress’s Dhirendranath Datta moved a motion in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan15, seeking the adoption of Bengali as an official state language (rashtra-bhasha) along with Urdu. He was shouted down, with even members from East Pakistan, including chief minister Khawaja Nazimuddin, opposing the motion.

Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali said Urdu was the only language that could keep the people of the eastern and western zones “jointed together” and alleged that the object of Datta’s motion was to strike at the unifying force that Urdu could become.

The response from the student community in Dhaka was instant and sharp.

Student leaders quickly formed the “Rashtra-bhasha Bangla Sangram Parishad” (State Language Action Committee) and called for a programme of protests on March 11. Sheikh Mujib was among those arrested that day in Dhaka and detained for five days — his first incarceration in Pakistan.

Pakistani Governor General Muhammad Ali Jinnah reiterated his government’s position when he came visiting a few days later. Once again, the student community registered its objection — with shouts of “na, na” (no, no) greeting the Quaid-e-Azam’s speech at a Dhaka University convocation.

That unhesitating expression of dissent was among the first indications of the role that students would play in the agitations that rocked East Pakistan in the later years, particularly in the mass uprising of 1969.

Jinnah said to have stood, silent and bemused, for a few moments before continuing with his speech. Perhaps he was taken aback. Perhaps, like his own Muslim League government at the centre and in the province, he had expected a docile submission from Bengalis.

But Bengalis had other ideas. If being Muslim had appeared to be the identity to be proclaimed before August 1947, being Bengali became, in a few months, the identity that needed to be protected.

Language movement of 1952

The language movement of March 1948, however, did not find resonance beyond a limited circle of students, teachers, and intellectuals. It did not spread outside the provincial capital. Even in Dhaka, the protesting students did not have much popular support. But the situation had changed by the time of the second language movement in early 1952.

This time the spark was provided by Nazimuddin, who, on his first visit to Dhaka as the prime minister16, declared that Urdu would remain the only state language, adding, for good measure, that research was underway on adopting the Arabic script for written Bengali.

The defiant violation of curfew by students in Dhaka on February 21, 1952, and the subsequent spilling of young blood in police firing is the stuff of legend, and we need not linger on it here. Sheikh Mujib was incarcerated17 during this agitation — shuffled around between jails in Dhaka, Gopalganj, Khulna, and Faridpur for some 27 months since his arrest in October 1949 over a face-off with the police during protests that marked prime minister Ali’s visit to Dhaka.

He was, however, in contact with political colleagues and was part of the discussions that called for action on February 21, the day the provincial assembly was scheduled to meet.

Unlike in 1948, the agitation this time had overwhelming popular support in Dhaka, and from February 22, it spread far beyond the capital, sucking in people from across the social spectrum. It was a spontaneous and unstoppable outburst — even schoolchildren refused to be left out of it.

What had changed in the intervening four years to make this possible?

Umar’s book traces how the repression unleashed by the provincial Muslim League government on the popular movements that washed over East Bengal in wave after wave in those early years radically changed the political consciousness of the people.

Concern for the mother language was no longer the preserve of the educated class. By 1952, people of all social classes were able to recognise it as an issue that directly affected them and their prospects in a system that would demand proficiency in Urdu.

Disenchantment and anger

By this time, too, the scales had fallen off their eyes. Everywhere in the province, the interests of the working classes —railway workers, post and telegraph workers, tea-garden workers, cotton-mill workers, dock workers — seemed to be the most dispensable on the government’s list of priorities.18

Between 1948 and 1950, people had watched how the state machinery fell upon popular movements with extraordinary and unnecessary brutality: the Nankar movement in Sylhet, where peasants rose against what was practically bonded labour; the agitation of the Hajong tribe in Mymensingh and Sylhet; and the Santhal movement in Sylhet.

From 1948, calculated sadism directed at inmates became routine in East Bengal prisons. The case of the legendary Ila Mitra, the communist leader of the Tebhaga movement in Rajshahi, and the torture and sexual violence she experienced in Nachole police station is well known. There were many other equally horrifying stories. Prisoners were killed inside jails in Dhaka, Khulna and Rajshahi districts.

In a particularly disturbing incident, a young student called Anwar Hossein had his skull blown off in firing inside Rajshahi prison in which nine others were also killed.

Unsurprisingly, the Muslim League in 1952 no longer had the support that it enjoyed in the 1940s when the hopes stoked by the Pakistan promise had propelled it to become a huge mass organisation in Bengal.

In Umar’s description, “They [Bengali Muslims] had hoped that once the independent Muslim state called Pakistan was established, the peasant would get land, the worker would get work and the assurance of a living wage, students would be able to access affordable and quality education, and educated young men would get suitable jobs and security of livelihood. They had further hoped that in Pakistan they would be able to nurture a healthy culture that would give fulfilment to their lives.”19

By 1952, it was clear that those hopes had been betrayed.

The remarkable speed with which the Muslim League lost acceptability must also be seen in the context of the near famine that prevailed in East Bengal in 1947. Apart from the physical suffering this caused, it was psychologically devastating for a population whose memories of the 1943 famine were still fresh.

For the next few years, the province continued to face a food crisis with artificial shortages created by flawed policy, grain-smuggling across the border to India (where prices were higher), and unethical stocking by landlords and grain merchants.

The discredited regime did not have the political will to control any of this. A democratic polity, with the promise of regular elections, still might have let off some steam and slowed down the League’s decline. But the regime embarked on a politically suicidal path of trying to crush all opposition, whether by force or by subterfuge20, and not holding elections.

In what was surely a pointer to where things were headed, the Muslim League lost the only election that was held at this time —the by-election to a provincial assembly seat in Tangail, then part of Mymensingh district, held in April 1949.

The Muslim League candidate, local landlord Khurram Khan Panni whose tenants accounted for most of the electorate, was defeated by Shamsul Haq, the first general secretary of the Awami League when it was formed a couple of months later.

Both central and provincial authorities lost credibility

Not only did the provincial government and its largely non-Bengali bureaucracy lose credibility, the central government soon became the villain in popular perception. Karachi, surely, held the strings controlling the puppet administration in Dhaka.

Such a situation naturally cried out for a viable opposition, no matter how hard the Muslim League tried to have the field left to itself. The only two political entities in East Bengal after Partition were the Muslim League and the Communist Party.21 While one had lost legitimacy in popular perception; the other was not quite in step with the bulk of the masses.

Into the political vacuum that was thus created stepped the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League, formed in June 1949 with Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani as the president and Haq as the general secretary. The 29-year-old Sheikh Mujib, who was in jail22 when the party was launched, was one of several joint general secretaries.23 Almost all the founder members were former (disillusioned) Muslim Leaguers.

The next part will discuss how the struggle for democracy and provincial autonomy in East Pakistan became inseparably linked with the rise of secular Bengali nationalism, which the Awami League came to represent under Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s leadership.

ENDNOTES

1 On the morning of August 15, 1975, people in Bangladesh woke up to a radio broadcast by Major Dalim, one of the core planners of the military coup that carried out the assassination. It went like this: “This is Major Dalim speaking. Sheikh Mujib has been killed. Bangladesh military has seized power under the leadership of popular leader Khondakar Mostaq Ahmad. Martial law has been imposed and there is a curfew across the country. Bangladesh from now on will be an Islamic republic.” (Translation by author)

2 After Pakistan was formed, the eastern wing was called East Bengal until the Constitution of 1956 changed its name to East Pakistan. The change was resented by Bengali nationalists such as Mujib.

3 Mujib was born in 1920 in the village of Tungipara in Gopalganj subdivision (now made a district) of Faridpur district. Mujib’s body lies buried in Tungipara.

4 Indeed, the university physically occupied the infrastructure that was in the process of being created for the new provincial capital of Dhaka. Dhaka University’s sprawling campus, with its many “halls” with residential quarters for teachers and hostels for students, was an inheritance left by a provincial capital that became redundant in 1911.

5 Rajshahi University was established in 1953 and the University of Chittagong in 1966. Jahangirnagar University was inaugurated in January 1971.

6 The group that carried out this movement was known as the Shikha Gosthi (Shikha group) after the Bengali journal Shikha (Flame) published by the Muslim Sahitya Samaj, or Muslim Literary Society, of Dhaka.

7 The 1923 Coconada session of the Indian National Congress rejected the Bengal Pact.

8 Mujib had completed his graduation in Calcutta from Islamia College, now named Maulana Azad College. After Partition, he enrolled as a law student in Dhaka University.

9 Tajuddin Ahmad, who from the mid-1960s served as the general secretary of the Awami League, headed Bangladesh’s government in exile, which took oath as the prime minister on April 17, 1971, at what came to be known an Mujibnagar in Kushtia. In Mujib’s absence, it was his able leadership and statesmanship that gave direction to the war of liberation and held it together in the face of factional feuds.

10 Abul Hashim, along with Hossein Shaheed Suhrawardy, and the Congress’s Sarat Chandra Bose and Kiran Shankar Roy, made a last-ditch attempt in May 1947 to stop the partitioning of Bengal and instead carve out an autonomous province that would have the right to choose whether it wanted to stay independent or join any of the two dominions of India and Pakistan.

11 Published by University Press Limited, Dhaka, June 2012, with introduction by Sheikh Hasina, Mujib’s eldest daughter and then the prime minister of Bangladesh.

12 Bengali-language newspaper that started publishing from Calcutta in 1936, edited by Maulana Akram Khan. It was an important mass media vehicle for Muslim aspirations in Bengal and Assam in the 1940s. The paper moved to Dhaka after Partition and aligned itself on the side of the language and later the nationalist movement in East Pakistan.

13 Page 15. Translated by author . An English translation of the book by Professor Fakrul Alam of Dhaka University, titled 'Unfinished Memoirs'.

14 Asamapto Atmojeeboni, page 28.

15 The session was held in Karachi, then the capital of Pakistan, presided over by then governor-general Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

16 Khawaja Nazimuddin, who was the first chief minister of East Bengal in Pakistan, became the governor- general of Pakistan following Jinnah’s death in September 1948 and the prime minister following the assassination of Liaquat Ali in October 1951.

17 Mujib started a fast in jail on February 16. He was released on February 28 after his condition became too alarming for the jail doctor to handle.

18 The second volume of Badruddin Umar’s book has an extensive discussion on this.

19 Badruddin Umar, East Bengal’s Language Movement and Contemporary Politics.

20 In order to scuttle opposition political activity, hired goons of the Muslim League often snatched microphones when political opponents tried to hold public meetings and also attempted to disrupt such meetings through violence. Government bodies frequently denied use of public buildings for indoor meetings.

21 The Congress lost its relevance after Partition.

22 Mujib was arrested in Dhaka in April 1949 during an agitation supporting the demands of Class 4 employees of the Dhaka University.

23 Among other joint secretaries were Ataur Rahman, Abdus Salam Khan, Ali Ahmad Khan, and Ali Amjad Khan.