Mujibur Rahman had feet of clay in post-war Bangladesh

The Awami League leader feared for his life as his grip on Bangladesh loosened fast, eventually leading to the fateful dawn of August 15, 1975

On August 15, 1975, the newly forged nation of Bangladesh was shaken to its core. A coup d'etat silenced the voice that had roared for Independence, and in the process, assassinated its architect, its father — Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

On the 50th anniversary of this dark day, here is the fourth and final part of a series exploring his life, enduring legacy, and his magnetic leadership. You can read the first, second and third parts here.

What happened after Bangabandhu’s return in January 1972 makes a painful story, but there was perhaps an element of inevitability about it. In the end, Mujib was consumed by the revolutionary transformation that he had brought about.

Mujib couldn't rise to post-war challenges

Like all great leaders in history, Mujib had feet of clay and could not rise to the challenges that post-war Bangladesh presented. It is doubtful that there was anyone else who would.

It is worth remembering that he had been absent from the scene of action during all three major movements that led to the birth of the nation, as the late Ghulam Murshid observed in the book Muktijuddha O Tarpor (The Liberation War and Thereafter) — published by Dhaka’s Prothoma Prokashan in 2010.

He was in jail during the language movement of 1952 and the uprising of 1969, and also during the liberation war of 1971.

Also read: Bangladesh to hold general elections in February 2026 amid rising voter apathy

It was Tajuddin Ahmad who headed the government-in-exile, handled the diplomatic exercise that turned the international community against the Pakistani military’s genocidal pogrom and steered the Bangladesh campaign to a successful close in the face of subversion and sabotage from within the movement.

Did Mujib feel a little challenged by Tajuddin’s successful leadership during the war? Was he perhaps apprehensive that his leadership was no longer undisputed? At any rate, one of his worst mistakes during this period was to allow a rift to grow between him and Tajuddin.

True, it was all done in Mujib’s name. He was named the president of Bangladesh by the government-in-exile. (Syed Nazrul Islam was acting president.) Worldwide, Mujib was the face that the movement became known by.

But Mujib himself, incarcerated in West Pakistan, knew nothing of what was happening until it was all over.

It is not inconceivable that after returning to Bangladesh in January 1972, he felt somewhat uneasy about Tajuddin. It was, so to speak, almost like Lord Ram coming back to sit on the throne that Bharat had kept warm and waiting for him.

Did Mujib feel a little challenged by Tajuddin’s successful leadership during the war? Was he perhaps apprehensive that his leadership was no longer undisputed? At any rate, one of his worst mistakes during this period was to allow a rift to grow between him and Tajuddin. It is said that Mujib never deigned to even ask Tajuddin about what happened during the nine months that he was away.

Also read: Yunus announces elections for February 2026, but is Bangladesh ready?

“Bangabandhu loved, trusted and respected Tajuddin,” wrote Rehman Sobhan.

“Between them, they provided the formidable and indestructible core to the direction of the liberation struggle. One of the post-liberation period’s deepest tragedies, culminating in the assassination of both Bangabandhu and Tajuddin1 in 1975, was the conspiracy by Tajuddin’s enemies to separate him from Bangabandhu.”2

The forces that were active against Tajuddin during the liberation war were the ones that now fed the coldness between Mujib and Tajuddin, — notably Sheikh Fazlul Haq Mani, a nephew of Mujib, and Khondakar Mostaq Ahmad, a senior Awami League leader who would later support the coup against Mujib.

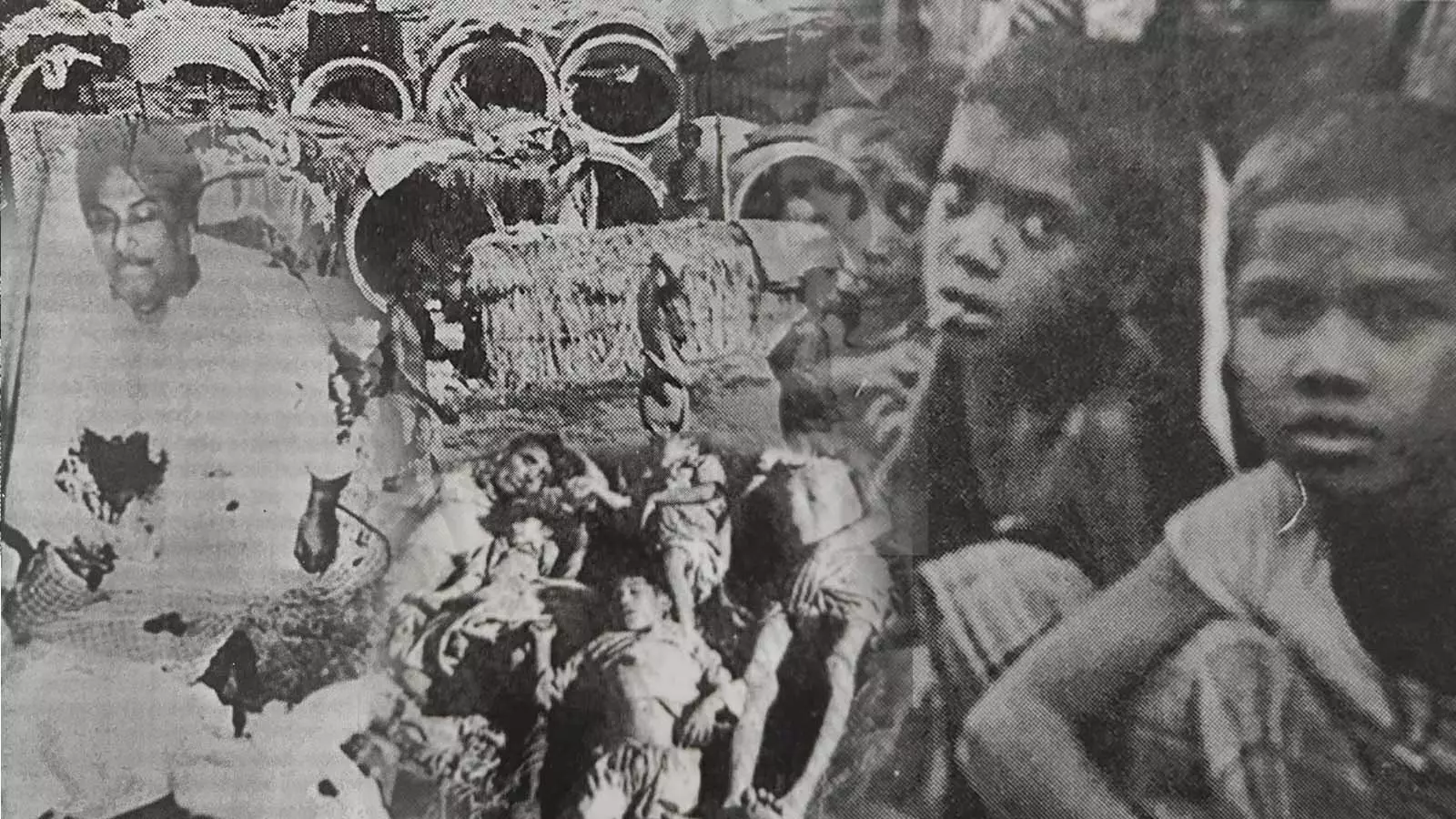

Musicians Pandit Ravi Shankar and George Harrison perform at The Concert for Bangladesh in New York, US, in August 1971. Picture credit: The book 'Muktijuddho o Tarpor' written by Ghulam Murshid, published by Prothoma Prokashon, Dhaka.

Sheikh Mani was part of a group of youth leaders who were opposed to Tajuddin’s leadership and made no secret of it during the war. There were tensions between the Mukti Bahini, controlled by the government-in-exile headed by Tajuddin, and Mujib Bahini, set up at the initiative of Mani and the other youth leaders. The Mujib Bahini kept trying to undermine Tajuddin’s authority.

Khondakar Mostaq Ahmad, who was a minister in Tajuddin’s Cabinet during the war, tried to scuttle the freedom movement by reaching out to the Pakistani establishment with proposals of a compromise. Mujib, who was made aware of this after his return in 1972, not only forgave him but, inexplicably, seemed to repose an inordinate faith in him.

As for Mani, Mujib had a soft corner for him, as he did for many of his relatives and friends.

Mani, whose activities contributed to Mujib’s steady loss of popularity, was killed in his home soon after his uncle’s assassination in 1975. Khondakar not only seized power, however briefly, after the coup but also described Mujib’s killers as “children of the sun”.

Travails of an inexperienced government

The Awami League formed the first government in liberated Bangladesh. Tajuddin stepped down as prime minister to make way for Mujib and was made the finance minister.

As Murshid has pointed out, the Awami League’s assumption of power was not as inevitable or even appropriate as it might appear at this distance in time. The party had won a huge mandate in 1970 for the movement for self-rule.

Also read: Awami League resistance turns deadly as Bangladesh govt’s political push falters

But though it led the freedom movement, it was not the only party that participated in that struggle. The Muzaffar Ahmad and Bhasani factions of the National Awami Party (NAP), the pro-Soviet Communist Party, and supporters of the Students Union of Dhaka University had all joined the movement.

Young students who had no party affiliation joined guerrilla groups and thought nothing of risking their lives for the country. Many peasants and workers who did not belong to any party had also joined the struggle.

Perhaps, says Murshid, a government of national unity, with representation from all stakeholders of the liberation struggle, would have been more appropriate.

But it did not happen.

What happened was that an inexperienced government led by the Awami League took charge. (Mujib had a brief experience as minister in the mid-1950s, for about a year.)

An impoverished and traumatised population expected this government to not only ensure food, clothes and shelter but also heal the wounds of war and dispense justice.

Also read: Bangladesh says Mymensingh building, set to be demolished, not linked to Satyajit Ray

The challenges posed by a devastated economy and war-ravaged infrastructure were formidable. The entire system of production and the supporting infrastructure had collapsed during the war — manufacturing industries, trade networks, distribution and civil supplies networks, export and import had all broken down.

Roads, bridges, and rail tracks all over the country were destroyed, either by Pakistani soldiers or by guerrilla units trying to thwart the military’s movements. Factories had stopped producing, properties had been looted, and educational institutions had barely functioned for a year.

As luck would have it, natural disasters further crippled Bangladesh’s chiefly agrarian economy in those initial years. A severe drought in the early months of 1972 was followed by floods in Sylhet (June), Sirajganj (July-August) and then Chandpur.

Khondakar Mostaq Ahmad, who was a minister in Tajuddin’s Cabinet during the war, tried to scuttle the freedom movement by reaching out to the Pakistani establishment with proposals of a compromise. Mujib, who was made aware of this after his return in 1972, not only forgave him but, inexplicably, seemed to repose an inordinate faith in him.

Unseen forces seemed to wreak a mindless fury on a hapless people through cyclones that year — in Mymensingh, Kishoreganj, Dhaka, and Laksam, killing people and livestock. Giant tidal waves crashing on coastal areas destroyed crops in Barishal and Khulna in December 1973.

The worst came in August 1974 when one-third of Bangladesh was inundated by floods. The long and short of it is that agricultural production took a hit in the years following liberation, and Bangladesh did not have the resources to prevent the famine that this led to in 1974, from August to October. Food security was already shaky in 1972, and hunger had started stalking the countryside from 1973.

Also read: Why should Sheikh Hasina submit to a sham tribunal in Bangladesh?

The international help that came in was apparently not enough, and to make matters worse, the US diverted two shiploads of food meant for Bangladesh to punish the country for trading with Cuba. As it always happens in such situations, the greed of hoarders made matters worse. Naturally, Mujib’s inexperienced government was held responsible for the situation in popular perception. Power has its pitfalls.

Unpopular decisions

Mujib, meanwhile, was taking one unpopular decision after another. He antagonised senior army officers by elevating General Safiullah as army chief, although he did not have the required seniority. (In 1975, Gen. Safiullah completely failed to protect Mujib from his assassins.) Worse, he appeared averse to investing in building up a strong and efficient army. Instead, he formed the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini (national protection force), a paramilitary force that became notorious as Mujib’s private army.

Some 8,000 liberation fighters (muktijoddha) were inducted into this force that did not have any code of conduct and were answerable to none but Mujib himself.

The terror tactics employed by it were a major factor in Mujib’s alienation from the people. So were the activities of the “Lal Bahini” (red army), a private militia maintained by a trade union affiliated to the ruling Awami League.

All this did not go down well with the armed forces. Murshid points out that Bengalis in the armed forces had rebelled against their Pakistani bosses to join the freedom movement, and while that reflected their commitment to the idea of Bangladesh, it also made them used to the idea of revolt. They had broken the chain of command once. In 1975, some of them were ready to take things into their own hands to correct what they saw as going wrong in the country.

Law and order broke down

Law and order had practically broken down after the war. The liberation war had left a large section of the population with access to arms, among both freedom fighters and collaborators. Freedom fighters had been supplied weapons by the Indian military while collaborators had been armed by the Pakistani military.

Soon after his return in 1972, Mujib called for the surrender of unlawful arms, but many were not ready to give these up. Though a large number of weapons were given up, many remained unrecovered.

This aggravated the law-and-order problem. The police force, which had suffered heavily during the war and was among the first victims of the Pakistani military action, was not equipped to handle the situation. Newly independent Bangladesh witnessed many incidents of police stations being looted, which led to the deployment of Rakkhi Bahini members to protect police stations. Ultra-left forces also turned out to be a destabilising factor.

The soaring inflation and deepening poverty not only worsened the law-and-order problem but whipped up a kind of rage among the people as they watched some Awami League leaders quickly becoming rich. Mujib himself maintained a simple lifestyle as always, and he did make some moves to check corruption within the party.

The post-liberation years witnessed a boom in smuggling, hoarding, and black-marketing activities, often with open patronage from Awami League leaders and legislators. As early as April 1972, Mujib threw out 16 legislators from the party and showed the door to another 19 in September. These measures were not enough, however, and he could not always display the same strictness to people close to him.

The question of collaborators

And then there was the question of collaborators. If the liberation war spawned stories of courage and resilience, it was also full of stories of betrayals and of Bengali collaborators leading Pakistani soldiers to freedom fighters, secular and progressive intellectuals, and, of course, Hindus. People who had suffered were now waiting for their leader to bring the culprits to justice.

But it was not always possible to tell collaborators apart from freedom fighters. For one, the collaborators were deeply embedded in society, sometimes sharing the same family living space with freedom fighters and Awami League sympathisers.

A “collaborator” father might have a son who had joined the war on the side of Bangladesh.

Many collaborators quickly changed colours after the regime changed. Some of these chameleons, with knowledge of who among their victims during the liberation struggle had capitulated, willy-nilly, and helped the Pakistani war effort, now blackmailed them with threats of exposure and extracted a price for keeping quiet.

Such threats were effective because many of the freedom fighters were now going around dispensing summary justice. There were also those who wheedled their way into positions of power.

The “freedom fighters” came with their own set of problems. The Mukti Bahini recruitments, at least in the initial phase, were heavily skewed in favour of Awami League workers and sympathisers3. This had some rather unfortunate consequences, as some of them allegedly went about settling personal scores in the countryside once they had weapons in their hands.

Mujib’s general amnesty for collaborators (barring those accused of murder, rape, arson) brought no solace to a society that was now deeply divided. Those who remained emotionally and intellectually invested in secular Bengali nationalism, especially the urban middle class that was completely loyal to Mujib in 1971, felt cheated and in later years, blamed his lack of firmness with collaborators and Pakistan loyalists for what happened to the country.

Mujib, dealing with lawlessness, a failing economy, natural disasters, and corrupt colleagues, often behaved, as many historians and journalists4 have recorded, like an autocrat in the way he appointed unsuitable people in positions they did not deserve to fill.

Worse, he acted like a village elder by micromanaging not only matters of administration but also disputes between people out to get a share of the pie. Murshid says this was in large part because Bangladesh was a tiny country where networks of kinship and friendship spread wide and deep.

When everyone knows everyone else, it is tempting for the leader to personally get involved in every small thing. In such a set-up, unpopular decisions can foster anger against the individual instead of against the system.

No checks and balances on power

The Awami League’s victory in the general elections of 1973 cemented Mujib’s dictatorial tendencies. It won 292 of the 300 seats. There were allegations that the elections were rigged. There were probably some instances of rigging, unlike in 1970 when the election was widely recognised as free and fair. Nevertheless, even without rigging, the Awami League would surely have won. It was still quite popular in March 1973.

But the victory had the effect of deepening Mujib’s faith in his own popularity. When he began to lose it, he did not apparently realise that the ground was shifting beneath his feet.

One of the things that crucially deepened Mujib’s growing unpopularity was the heavy-handed way in which he tried to suppress workers’ revolts. His vision was socialist, and a just distribution of wealth was his aim in the long run. In the difficult and strife-torn short run, however, he tried to stop the workers from making too much noise about their dues.

The Rakkhi Bahini, Lal Bahini, and the Awami Chhatra League were his instruments in this effort. The once tireless champion of democracy was not able to grant democratic space for opposition and dissent. The regime became notorious for police action on protesters.

The opposition in Bangladesh’s newly elected legislature was too weak to act as a check on the ruling party. Ironically, Mujib, who had recorded in his autobiography how the Muslim League lost acceptability by trying to throttle the voice of the opposition, tried to suppress criticism by curtailing the powers of the judiciary and clamping down on press freedom.

In a country that was now used to violence as a means of settling disputes, this only led to a culture of back-stabbing and assassinations. The Awami League and its student supporters became part of this muscle-flexing culture. Incidents of police firing on protesting students seemed to complete a cycle and brought back memories of the Pakistani regime.

Resurfacing of dormant tendencies

Perhaps the development that contributed most to Mujib’s vulnerability after 1972 was the resurfacing of ideologies that had been suppressed by the nationalist and anti-Pakistan sentiments of the 1969-1971 period. Even during that time, some views did not favour a rupture with Pakistan, both among the general population and in political parties.

After 1972, fears about “big brother” India calling the shots created fertile ground for communal and pro-Pakistan forces to rear their head again. Secular Bengali nationalism was now suspect because it held out the promise that Bangladesh also belonged to its Hindu minority, as much as it did to its Muslim majority. This promise sharpened fears about the Mujib government potentially becoming a puppet in the hands of “Hindu” India.

The poet Nirmalendu Goon, who returned to village home after Mujib’s assassination because he was too disturbed to stay in Dhaka, heard stories about a Muslim man who, bare-bodied and with a kerchief tied on his head, went running around the village upon hearing the news of the assassination. The “father of the Hindus” was dead and there was no need for any fear anymore, he screamed and urged fellow Muslims to come out and celebrate5.

As insidious campaigns branding Mujib and his followers as “Indian agents” gained ground, right-wingers within the Awami League and among student activists became more assertive.

In the midst of all this, Mujib, painfully aware that he was the leader of a small, impoverished and underdeveloped nation, was keen to get recognition from the international community and ready to make compromises to that end.

Notwithstanding all Mujib’s failures, the one thing that secures his place in history is his legitimising the idea of secular Bengali nationalism. He was not its only champion but was certainly its most visible and charismatic face.

The formation of BAKSHAL — Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League — in 1975 was Mujib’s final (desperate?) attempt to hold the nation together. But the transition to a presidential system of governance only undermined his status as a democrat. Tajuddin, whom Mujib had dropped from his ministry in late 1974, was not a member of the rubber stamp Cabinet that now took oath under Mujib as the all-powerful president.

Mujib had already closed all legitimate routes of protest. Now, all political parties apart from BAKSHAL, which was little more than the Awami League in a new avatar, were outlawed. Murshid records having read in an article published in the daily newspaper Prothom Alo in 2008 that Tajuddin’s response to the whole exercise was to phone Bangabandhu to say, “Mujib bhai, you have left no way of removing yourself except through a bullet.”

Fear of death?

Abdul Gaffar Chaudhury, famous for his song on the 1952 language movement (Amar bhaier rakte rangano ekushe february — "Drenched in the blood of my brothers, the 21st of February"), has said in his memoirs6 that Mujib started fearing for his life from the end of 1973. He seemed to have been sure that he would die an unnatural death and was disturbed by the military coup that got rid of Chile’s Salvador Allende. He was in a hurry to finish what he had set out to do and seemed to know that he did not have much time.

“A bullet is chasing me,” he told Chaudhury weeks before his death.

Yet, he also often expressed confidence that he was too well-loved in Bangladesh to be unsafe. Former Indian PM Indira Gandhi and the Cuban leader Fidel Castro are said to have warned him that a plot was afoot to kill him. He did not take the warnings seriously and apparently did nothing to tighten his security. The assassins seemed to have got to him with amazing ease at his Dhanmondi residence7 on the dawn of August 15, 1975. (Mujib had never moved to official accommodation for the head of state and only used it as his office. He came back home every evening to Dhanmondi.)

The circumstances of Mujib’s assassination have never been wholly cleared up.

Was it just a coup by a group of disgruntled army officers? Were there foreign powers involved? Was it Pakistan extracting its revenge? Did the CIA have a role in it? It might never be known. About the only thing that can be said with certainty is the rise of fundamentalism and right-wing politics in post-Mujib Bangladesh. The Awami League regimes under his daughter were unable to significantly reverse this trend.

Yet, notwithstanding all Mujib’s failures, the one thing that secures his place in history is his legitimising of the idea of secular Bengali nationalism. He was not its only champion but was certainly its most visible and charismatic face, one that linked this idea with aspirations for democracy and freedom. The cornerstones of the Constitution that he gifted to the new nation in 1972 were secularism, democracy, socialism, and nationalism.

It was not the kind of nationalism that creates an identity by stressing differences and building walls. By emphasising the linguistic oneness of Bengalis across an ancient religious divide, secular Bengali nationalism from the very outset allowed Bengalis of East Bengal/East Pakistan/Bangladesh to lay claim to a common cultural heritage.

It is this breadth of outlook, missing in most Bengalis from West Bengal, that allowed secular Bengali nationalism to have its face turned outward to the world from its inception, and not inward within itself. Mujib will always remain the father of the nation for those who believe in this worldview.

Like the Mahatma in India, it was Bangabandhu’s destiny to fall to an assassin’s bullet. Perhaps there is nothing more endearing about his memory than the fact that he was not a “mahatma” but a “bandhu”, a friend of Bengalis everywhere.

To deny his role in the birth of Bangladesh’s Bengali-speaking nation is to deny history. And that, as Bangladesh has discovered to its cost, always extracts a price.

END NOTES

1 Tajuddin was arrested and put behind bars after Mujib’s assassination, along with three other Awami League old-timers who had been Mujib’s most trusted colleagues and had formed the government-in-exile —Syed Nazrul Islam, Mansoor Ali and A.H.M Qamruzzaman. They were all assassinated in jail in November 1975.

2 See Rehman Sobhan, Untranquil Recollections

3 Anisuzzaman records in his memoirs Amar Ekattor (My 1971) that he warned Tajuddin, whom he held in immense respect, about this.

4 Notably Anthony Mascarenhans in The Legacy of Blood.

5 Nirmalendu Goon, Raktajhora November (A bloodied November), Kathaprokash, Dhaka, 2013.

6 Itihasher Raktapolash: Poneroi August, Pochattor (History’s Flame of the Forest, 15th August 1975), Agamee Prakashani, Dhaka, 2017.

7 This historic dwelling place of Bangabandhu was destroyed by a violent mob in February 2025.