When Mujibur Rahman was branded India’s agent

Right-wing political opponents tried to run many campaigns, but such efforts were blown away in the pro-Mujib gale

On August 15, 1975, the newly forged nation of Bangladesh was shaken to its core. A coup d'etat silenced the voice that had roared for Independence, and in the process, assassinated its architect, its father -- Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

On the 50th anniversary of this dark day, here is the third of a four-part series exploring his life, enduring legacy, and his magnetic leadership. You can read the first and second parts here.

Both wings of Pakistan witnessed pro-democracy agitations in 1969. Although Ayub Khan was replaced by another military ruler and a fresh martial law regime in March that year, Yahya Khan came with the promise of holding elections that would be followed by a transfer of power to elected representatives.

These would be Pakistan’s first parliamentary elections based on universal adult franchise.

Also read: Bangladesh to hold general elections in February 2026 amid rising voter apathy

Mujib stood by his Six Points (and the Chhatra Sangram Parishad’s 11 Points) at the round table conference (RTC) that was held in Islamabad in February-March 1969. He travelled to the Pakistani capital with the knowledge that the recent movement in East Pakistan reflected the people’s impatience for self-rule. As it turned out, the RTC was neither here nor there because Ayub was anyway on his way out and knew it.

But Mujib, with three years’ incarceration scarcely behind him, had a team of economists with him to help him present his case for Six Points at the RTC.1

The pitch for Six Points informed the Awami League’s campaign for the December 1970 elections. The election would be Mujib’s key to secure people’s endorsement for this blueprint for autonomy.

Bangladesh’s liberation war had its fair share of sabotage and subversion, as all such epochal events invariably do. But in 1971, the vast majority had found in Mujib a symbol of their aspirations for liberation, and his detractors lost their voice.

But though it was the charter that had the Pakistani establishment rattled, the Awami League election manifesto also held enough cause for consternation in the radical economic reforms that it proposed.

Awami League's socialist vision

Rehman Sobhan, who had helped to put the manifesto together in his capacity as an economist, explains in his memoir why this was necessary.

“[T]he reality of 1969 East Pakistan demanded that Bangabandhu must reach out to a broader national constituency where the great majority of households were working people. … It was this large constituency of the deprived who could invest him with the massive mandate he needed to politically challenge the military and who would stand by him if this confrontation could not be resolved through the democratic process route.

Also read: Awami League resistance turns deadly as Bangladesh govt’s political push falters

“In such a confrontation, Bangabandhu, more than any radical politician, realized that the emerging Bangali bourgeoisie, who were rapidly climbing onto his political bandwagon after 1969, were important but unreliable allies. He apprehended that when the moment of truth arrived, to stand up to the might of the Pakistan army, this class would be the first to press for a compromise on the struggle for self-rule.”2

Does this mean Mujib could foresee the genocide unleashed by Yahya’s regime in 1971? Perhaps, but again, maybe not. Genocide or not, that the Pakistan military could be used to ruthlessly suppress a popular movement was a no-brainer; and Mujib would have realised the need to be prepared for a violent crackdown.

The history of Pakistan, after all, was littered with compromises by East Pakistani politicians who betrayed the interests of the province for a share of power at the centre.

In any case, Mujib’s faith in the electoral process as reflecting popular will was evident through most of his political life. Indeed, it must have deepened in a regime that for so long had refused to hold elections based on universal adult franchise. He has left enough evidence of this in his Asamapto Atmajeebani (Unfinished Autobiography), which traces his early political life in great detail.

In the 1940s, elections in undivided Bengal had established Bengali Muslims’ support for partition. The Tangail by-election in 1949 had shown the Muslim League was losing support, and the 1954 provincial assembly polls had conclusively proved this. Now, elections were about to prove East Pakistan would settle for nothing short of self-rule.

Also read: Why should Sheikh Hasina submit to a sham tribunal in Bangladesh?

The Awami League’s election manifesto reached out to the subaltern classes with the promise of a redistribution of wealth. It proposed to abolish the feudal systems of landholding (jagirdari, zamindari, sardari) in West Pakistan; and introduce land reforms in favour of actual tillers of the soil throughout the country.

All landholdings would be subject to a ceiling and the excess land would be redistributed. Holdings up to 25 bighas, or 8.33 acres, would be exempt from tax and tax arrears waived. The manifesto envisioned a socialist economy through nationalisation and cooperative enterprises.

The manifesto was ratified by a party council on June 6, 1970, but Mujib had flung himself into the election campaign as soon as open political activity was permitted from January 1. He had been locked up from May 1966 to February 1969, and some of his closest aides such as Tajuddin were also jailed during this time.

Also read: Ex-Bangladesh PM Hasina indicted in crimes against humanity case

Other players, including reckless young student leaders, had filled the political vacuum this must have created. The long campaign for the 1970 election3 gave Mujib the opportunity he needed to reconnect with the people.

Bangabandhu’s election campaign

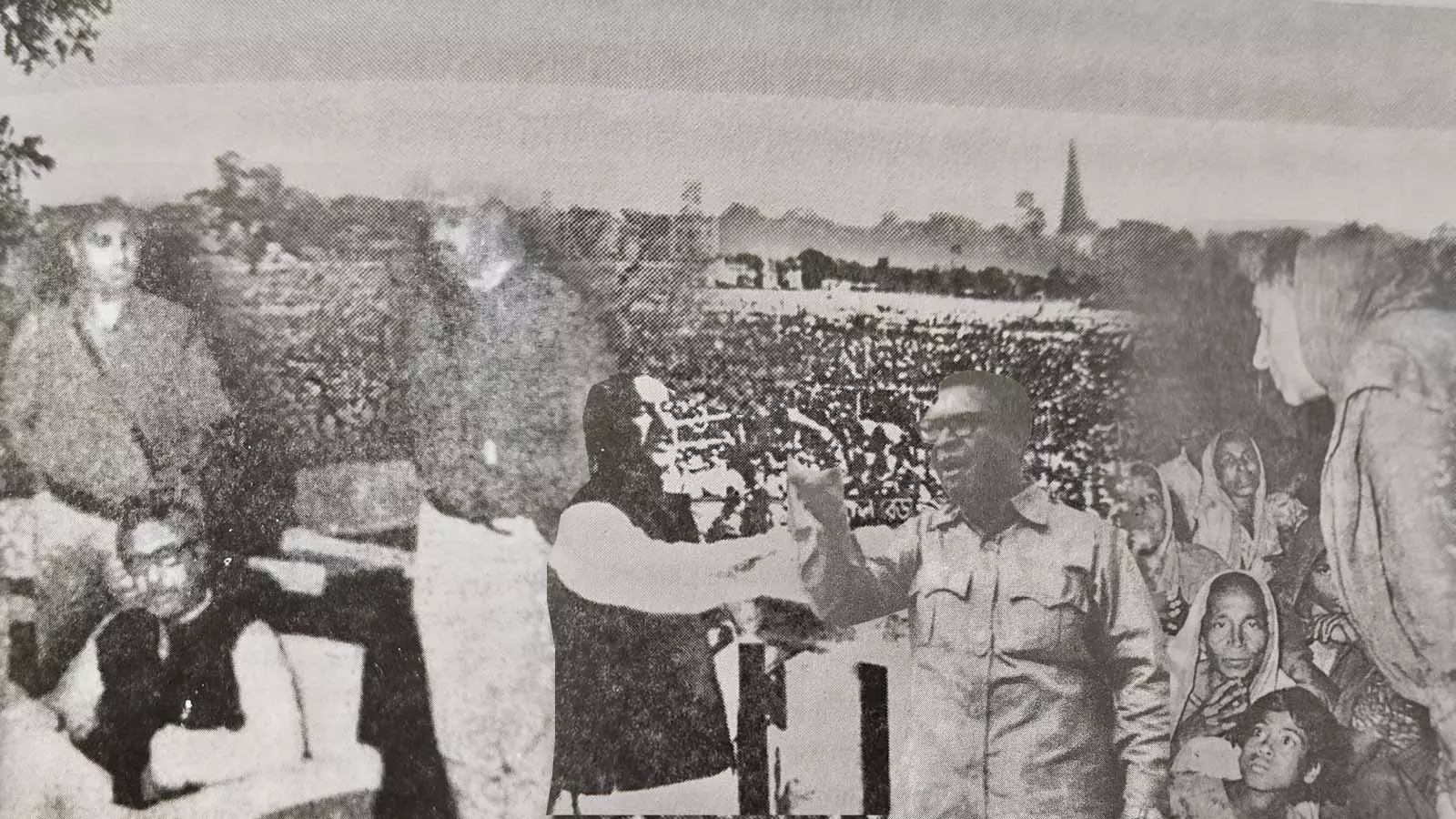

For 11 months, records Sobhan in his memoir, “Bangabandhu surged across the province like a tidal bore sweeping all before him. … By December, there was not a single household in Bangladesh that did not know what the election was all about and who was Bangabandhu.”

The Awami League won 160 of the 162 parliamentary seats of East Pakistan in the general election conducted on December 7, and seven seats reserved for women, which made it the party holding the majority in the national assembly. Naturally, it also won absolute majority in provincial assembly elections held a few days later.

By all accounts, Mujib was the face of the Awami League at this time and it was for him that people voted — like the peasant who, when asked by an Awami League candidate whether he would vote for him, said he would vote for “Mujeebuddin”.

Also read: India slams Bangladesh over Durga temple demolition in Dhaka

Sobhan has described one of the campaign trips where he accompanied Mujib: “I travelled with Bangabandhu from Dhaka to Kaliganj, where he was to address an election rally in Tajuddin’s constituency. En route, at Adamji Nagar, the entire workforce had assembled en masse to greet Bangabandhu and pledge their support to him. From Narayanganj launch terminal to Kaliganj, the riverbanks were packed with cheering crowds along every inch of the route. … In the minds of the common people, Bangabandhu had been transformed from a political leader into the personification of their hopes and dreams.”4

In Nirmalendu Goon’s words, “People started responding to Bangabandhu’s call in the way the Bengali mind responds to the cuckoo’s song when spring arrives. Wherever he went, the largest ever crowds in living memory would turn out.”5

Right-wing political opponents tried to run campaigns branding Mujib as India’s agent and an enemy of Islam; and even Maulana Bhasani’s National Awami Party attempted a disruption in the electoral process by boycotting the election at the eleventh hour. Such efforts were blown away in the pro-Mujib gale that blew across East Pakistan at this time.

A stunning mandate

The election result upset the junta’s calculations. It had expected the Awami League to win but was banking on a more fractured outcome that would potentially thwart Mujib’s push for self-rule. Yahya’s Legal Framework Order (LFO)6, announced on March 30, 1970, provided an escape route by ensuring that a democratic transition would not be allowed without the junta’s approval.

Mujib had chosen to ignore it and banked on the election mandate to carry the day for him.

Also read: Why Bangladesh will be on a knife-edge till 2026 elections

Now, there was an impasse. Yahya Khan could not brook a Constituent Assembly (comprising newly elected members of the legislature) session where the Awami League, by virtue of its majority, would be able to take forward the Six Points agenda.

The Awami League won 160 of the 162 parliamentary seats of East Pakistan in the general election conducted on December 7, and seven seats reserved for women, which made it the party holding the majority in the national assembly.

The stunning victory also restricted Mujib’s own choices through its unambiguous assertion of a popular mandate in favour of Six Points. He could not have compromised on it now even if he wanted to.

It would be seen as a betrayal of the people and extremist sections in his own party would be seriously antagonised — especially firebrand youth leaders like the Four Caliphas (as they were called), ASM Abdur Rab, Shahjahan Siraj, Abdul Kuddus Makhan, and Nure Alam Siddiqui, who believed it was time to openly demand complete independence.

On March 17, the poet Sufia Kamal wrote in her diary, “… Mujib is a prisoner in the hands of the people, Yahya in the hands of the army.”7

It was not entirely true. As a military dictator, Yahya functioned like an autocrat, often against the better advice from within his own establishment. Mujib, aware that the people’s aspiration for freedom was mounting every day, tried until the end to find a democratic solution without compromising on the autonomy demand.

On January 3, at a public meeting attended by thousands in Dhaka, Mujib swore in all elected Constituent Assembly members of the Awami League to absolute allegiance to self-rule. Did this, perhaps, show Mujib’s unease about some of his own legislators’ commitment to the self-rule agenda? Was he apprehensive that some of them might crumble under pressure and lean towards a compromise?

The history of Pakistan, after all, was littered with compromises by East Pakistani politicians who betrayed the interests of the province for a share of power at the centre. Was the swearing-in ceremony an instance of Mujib using his own undisputed leadership to nip such possibilities in the bud?

Sobhan has recorded his unease with how the election manifesto was passed without a murmur at the party council in June 1970: “Bangabandhu presented the document to the council as reflecting his own vision that brooked no challenge then or later when he was in power. This may have pleased his advisers but was not good omen for the party where policy proposals needed to be exposed to debate before being adopted.”8

Undercurrents of dissenting views must have been present even then, as later events subsequently proved — events that would lead to the assassination in 1975. Bangladesh’s liberation war had its fair share of sabotage and subversion, as all such epochal events invariably do.

But in 1971, the vast majority had found in Mujib a symbol of their aspirations for liberation, and his detractors lost their voice.

Non-cooperation in March 1971

In the face of this overwhelming support for Mujib and his intractability over Six Points, Yahya naturally dithered over the Constituent Assembly session scheduled for March 3 in Dhaka. On March 1, in a message broadcast by Pakistan Radio, he announced it adjourned sine die.

That foolhardy act, against which more circumspect individuals in the Pakistani establishment pleaded, unsuccessfully, with Yahya9, hastened the birth of Bangladesh. Speculation had been rife about a conspiracy being hatched in Islamabad, especially after reports of Yahya’s duck-shooting “vacation” with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto10 in Larkana in Pakistan immediately after the inconclusive Yahya- Mujib meeting in mid-January. The adjournment seemed to confirm those fears.

On March 1, Jahanara Imam’s two sons, Rumi and Jami, were watching a cricket match between Pakistan and the Marylebone Cricket Club at the stadium on what was until recently called Bangabandhu Avenue11. In her Ekattorer Dinguli12, she recorded Rumi’s narration of how the spectators, many of whom had transistor sets with them, left the stadium shouting “Jai Bangla” as soon the adjournment announcement was heard.

Within an hour, thousands of people, shouting slogans, jammed the streets leading to Purbani Hotel where Mujib was in a meeting with elected legislators from his party. In an action symbolic of their resistance to the adjournment, they carried bamboo sticks and iron rods, the easiest weapons they could lay their hands on at such short notice.

At Dhaka University, students left their classrooms in droves and within a couple of hours registered their protest at a public meeting attended by many. The writing on the wall was clear.

At a hastily announced press conference at Purbani Hotel, Mujib called for a hartal (strike) in Dhaka the following day and another across East Pakistan on March 3.

What followed next probably remains unique in the history of modern nations — a non-cooperation movement of unprecedented proportions that lasted until the night of March 25 when Pakistan launched Operation Searchlight and Mujib declared Bangladesh was free.

In the first few days, the administration made an attempt to assert its authority by declaring a night curfew and trying to enforce it with the army’s help (Bengali policemen were refusing to act against fellow Bengalis).

People came out anyway and braved the army’s bullets, leading to casualties, more protests, and funeral processions and prayers joined by just about everyone except those who were housebound because of compelling circumstances.

By March 4, Chief Martial Law Administrator General Yakub, who was now also acting as governor, realised it was useless to try to quell the protests and recalled the troops to the barracks. Effectively, this amounted to a relinquishing of authority.

Describing the turn that the non-cooperation movement took from March 5, Sobhan writes: “The entire civilian bureaucracy, the police force and all components of the provincial and central government ceased to extend their services to the established government. The apogee of the non-cooperation movement was reached when the then Chief Justice of East Pakistan, Badruddin Siddiki, declined to swear in General Tikka Khan as the new Governor of East Pakistan.

“The non-cooperation movement graduated to a qualitatively different level when all the different echelons of the machinery of government sent their representative to Road 32, Dhanmondi, to pledge their allegiance to Bangabandhu. The bureaucrats were shortly followed by the business community, then dominated by non-Bengalis, who also pledged their support.

“The world has witnessed many such movements but, to the best of my knowledge, none has reached a point where the administration, the police force and the law courts have decided to not only disobey the orders of an incumbent government but have gone on to pledge allegiance to a political leader who held no formal office.”13

‘No fear anywhere anymore’

The best account of what those days of non-cooperation were like can be found in Jahanara Imam’s Ekattorer Dinguli and also in Sufa Kamal’s Ekttorer Diary (1971 Diary)14. All educational institutions were closed. Mujib ordered all banks and government as well as private sector offices to remain open from 2:30 pm to 4 pm so that the system could be kept running. All vendors, shopkeepers, cabbies, and rickshaw-pullers also followed this timing. With nothing to do for the rest of the day, people visited neighbours and friends and endlessly discussed the political situation.

Poets found that, at last, they could record poems for radio that earlier would not have stood a chance. Television offered musical programmes where singers such as Firdausi Rahman, Sabina Yasmin, Shahnaz Begum, and Rathindranath Roy sang songs of struggle and protest. Writers and artists frequently got together for meetings and took out processions.

“Many processions, many meetings, lots of people on the streets, all past caring for safety. The sweet taste of death is driving them crazy. No fear anywhere anymore.”15

No one really believed that the talks between Mujib and Yahya (who arrived in Dhaka on March 15; Bhutto arrived a few days later) would yield anything, and nor did the steady troop build-up escape people’s notice. Restive young people prepared for a possible conflict situation and were quietly encouraged by the Awami League leadership to do so.

Dhaka University students and non-teaching staff practised a military-style drill on the premises every day. Many Awami League workers and students had started building up a stockpile of weapons (which could accord no protection to the city when army tanks rolled out of the barracks on the night of March 25) and built barricades in anticipation of military action.

Now and then, there were reports of clashes between Bengalis and Biharis in Chittagong. Most accounts agree that on the whole Awami League workers were able to enforce some sort of order and maintain peace.

That the people now thought of themselves as a free nation was past all doubt on March 23, observed as “resistance day”, when homes everywhere sported the flag16 of free Bangladesh alongside black flag of protest.

Mujib’s March 7 speech

And that brings us to the historic speech of March 7, 1971, at the Ramna Racecourse. Goon has called it a “political poem” worthy of being ranked among the most valuable intellectual properties of Bangladesh. It is remembered for the perfect balancing act that it was, poised on the cusp of a great churning among the people who had turned Mujib into an icon.

Bengalis received it, rightly, as a declaration of freedom, and yet it was a speech delivered within the constitutional parameters of a united Pakistan.

On March 6, Yahya’s radio address to the nation had held out a warning: He would not concede power to a handful of East Pakistani opportunists as long as he had his army and navy. This caveat, coupled with his bad-tempered scolding, did not make his announcement of a national assembly session on March 25 very reassuring.

Threat of army action was the dominant impression left by the president’s address, not the promise of democratic process.

Provoked by Yahya’s aggressive posturing, Bengalis waited with bated breath for Mujib’s speech the following day, which was supposed to be aired over radio. (The Pakistani establishment chickened out at the last moment and stopped the broadcast but was forced to air it the next day following a revolt by Bengali radio employees.)

The historic speech was not read out from a written script. Equally, it was not extemporaneous. The Awami League leadership had brainstormed over it all through the previous day and night, and the final decision ruled out a declaration of independence. No one at this stage had any clear idea about how prepared the people were to withstand a military crackdown, let alone genocide.

Also, a premature call for independence would get the Bangladesh movement branded as “secessionist”. This would deny it the legitimacy that it eventually achieved on the global stage. And yet, that the people of East Pakistan were already free in their minds and hearts could not be ignored at this point.

This was the paradox that Mujib carried on his shoulders when he stood before an estimated 30 lakh people17 that afternoon. He came a little late, and sitting in the front row, Sufia Kamal, thought he looked tired and sad. The icon was also a human being weighed down by what the near future was about to unleash.

But when he spoke it was as if “someone sitting within him was supplying his voice with word after word, sentence after sentence, best word in best order. It was a veritable waterfall, a fountain of words that came out of him. ... He who had been eagerly awaited that day by a sea of fervent, rebellious people who started arriving from dawn was a poet.”18

This may be the emotional response of a poet (Goon), but most first-hand accounts testify that the listeners were deeply moved. The speech was truly remarkable for how well-thought-out it was.

By refraining from declaring Bangladesh was free and independent, to the disappointment of party hardliners and enthusiastic young supporters, he made sure that the movement could not be called secessionist. He also made it clear that he preferred a political solution through dialogue, but not at gunpoint and not at the cost of self-rule.

Mujib's four conditions

Mujib spelt out four conditions for the Awami League’s participation in the Constituent Assembly session on March 25: withdrawal of martial law; confining soldiers (“our brothers’) to the cantonments; transfer of power to elected legislators; and a judicial inquiry into the deaths caused by army action in the beginning of March.

None of these demands could be called unreasonable. His message for Bengalis was: We have tried all we could to find a peaceful solution, but now prepare to defend yourselves with whatever you have, let every home become a fortress.

During the dark months of the liberation war, many homes did indeed become fortresses with the help and support they provided to guerilla units fighting the occupation.

Military action and Mujib’s arrest

On the night of March 25, when it became clear that military action was starting, there was no longer any reason to hold back a declaration of freedom19.

That night Bangabandhu opted to stay at home and wait for arrest, against the pleading of scores of his colleagues, well-wishers, and followers who urged him to flee. This final act of selfless courage and far-sightedness probably seals Mujib’s claim to the title of “father of the nation”. He chose not to evade arrest because he apprehended that the Pakistani military would vent its fury at the people if its prize catch slipped through its fingers.

Trying to escape might also have been quite pointless because, surely, Pakistani military intelligence had him covered 24/7. Most importantly, it did not stop anything. He had directed a close group of colleagues, including the brilliant and statesmanlike Tajuddin, to escape and cross the border into India to organise a freedom struggle from its soil. Tajuddin did not disappoint him.

Bangabandhu’s insightful leadership through the excruciating tensions of the preceding weeks had already made nonsense of Pakistan’s legitimacy as the arbiter of the eastern wing’s destiny.

The authority that Pakistan lost at the start of the non-cooperation movement in March was never regained. The fierce military action on March 25 and the genocide that followed it reinforced Pakistan’s status as an occupying force, both to Bengalis and to the international community.

The next and final part will briefly look at some of the things that went wrong in post-1972 Bangladesh and the assassination that changed the course that the young nation was setting out for itself.

END NOTES

1 See Rehman Sobhan, Untranquil Recollections, Sage Publications, New Delhi, 2016. Page 283-284: ‘In order to project his demands to the RTC in more professional terms, he took Kamal Hossain, as well as Sarwar Murshid and Muzaffar Ahmed Chowdhury from Dhaka University, along with him to Islamabad. He also brought in Nurul Islam from Karachi, along with Anisur Rahman and Wahedul Huq, who were then both professors at the Department of Economics in Islamabad University, to help him prepare his presentation.”

2 Ibid.

3 The parliamentary elections held on December 7 were the first parliamentary elections based on universal adult franchise in the history of Pakistan. Initially planned for October, the elections were postponed because of floods in East Pakistan. There was talk of postponing the elections again after the hurricane that ravaged the southern coastal districts of East Pakistan in November, but Mujib would not hear of it.

4 Untranquil Recollections, Sage Publications, New Delhi, 2016. Page 310.

5 Amar Kanthoswar.

6 The LFO was meant to provide a constitutional basis for an election based on universal adult franchise. It mandated that the elected national assembly of 313 members would have to frame a Constitution within 120 days of getting elected.

7 Sufia Kamal, Ekattorer Diary (Diary 1971), Hawladar Prokashoni, Dhaka, 1989.

8 Ibid, Page 294.

9 Admiral S.M. Ahsan, who was Governor of East Pakistan from September 1969 until he was removed in March 1971, and Lt Gen Sahibzada Yakub Khan, who was Chief Martial Law Administrator in East Pakistan, had both tried to dissuade Yahya from calling off the Constituent Assembly session scheduled for March 3. Sobhan says in Untranquil Recollections (page 325) that they both confirmed this to him later. “Ahsan will be remembered by history as a genuinely decent man who did all in his power to not only ensure a free and fair election in December 1970 but tried, until the last moment, to work for a peaceful democratic transition.”

10 Bhutto, with his Pakistan People’s Party wining 81 out of the 138 parliamentary seats in West Pakistan, was a newfound ally of Yahya. Newfound because Bhutto with his PPP’s putative challenge to West Pakistan’s feudal oligarchy had not been in favour before the election. After the election, Bhutto could be used to challenge the Awami League’s domination in the Constituent Assembly.

11 Renamed in March 2025 as Abrar Fahad Avenue.

12 Memoirs of the Days of Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971, Jahanara Imam, Charulipi Prokashan. First published in 1986.

13 Untranquil Recollections, page 327-328.

14 Sufia Kamal, Ekattorer Diary, Hawladar Prokashoni, Dhaka, 1989.

15 Ibid.

16 At this stage the flag had a map of Bangladesh on the red sun set against the green background. After the conclusive victory of liberation forces in December 1971, the map was dropped from the flag.

17 Ekattorer Dinguli. In Jahanara Imam’s memory of what she heard from her husband and son, “nearly 30 lakh people came to the meeting in the racecourse maidan. There’s no count of all the people who came walking in processions from far-off places, carrying sticks and rods on their shoulders. Certainly from places like Tongi, Jaidebpur, Demra — a huge procession of people who had walked for 24 hours from Ghorashal also came to the meeting, with jaggery and flattened rice to sustain them on the way. I was astonished to hear of how a procession of blind boys walked to the meeting. Many women and girl students arrived in a procession to hear the Sheikh speak.”

18 Amar Kanthaswar.

19 The message said: “This may be my last message, from today Bangladesh is independent. I call upon the people of Bangladesh wherever you might be and with whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from the soil of Bangladesh and final victory is achieved.” It was transmitted on the night of March 25-26, 1971, on a wavelength close to that of Pakistan Radio so that people would be able to catch it in East Pakistan. Subahdar Major Shaukat Ali of Signal Corps, East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) transmitted the message from equipment that he had put together in his official quarters. He was caught, tortured, and shot dead by the Pakistan Army. Four of his five colleagues who were caught were also killed; one survived miraculously.