A series of murders and tragedies in Lahore shape Kashmir’s destiny

The Story of Kashmir’s integration with India

As part of our series on Operation Gulmarg, Pakistan’s failed attempt to invade Kashmir in 1947, we flip the pages of history to understand how the state came under the British, marking the beginning of its troubled tryst with destiny

A series of murders and tragedies in Lahore shape Kashmir’s destiny

Uploaded 05 November, 2020

Dawn broke over Lahore on June 27, 1839, like any other day. The sun’s rays kissed the Fort’s turrets, sped past its Alamigiri Gate, rustled through the grass blades of Hazuri Bagh and then scattered over the water of the river on its west.

On any other summer day, when the heat of the subcontinent and the humidity unleashed by the monsoon gathering over its western borders made life difficult in Lahore, the Maharaja would have been in Dina Nagar, his retreat on the border of the state of Jammu in the north. But, that year, the Sher of Punjab couldn’t leave Lahore because of his health.

Sarkar Sahab Ranjit Singh had tried everything to regain what he had lost because of a stroke, rheumatic pains, dropsy, locked jaw and failing liver attributed to his love for what the British called liquid fire—a concoction of strong spirits, sauces made from pastes of animals and birds, opium, and powdered gems and precious stones.

Doctors and hakims from throughout Ranjit Singh’s empire were summoned to revive his failing 58-year-old body. Large sums of Nanakshahi rupees forged in his own mint were gifted to holy men, peers, padris and sadhus throughout the kingdom. Jagirs were assigned to temples, gurudwaras and mosques along with precious pearls, diamonds, cows, horses and elephants with howdahs carved from gold. But, by the middle of June, Sarkar, the one-eyed Sikh who had battled small pox, Marathas, Afghans and the British to establish the rule of the Khalsa from Amritsar in the south to Kashmir in the north, knew he had become la-ilaaz.

Around 5 pm, when a sharp wail like the howling of jackals rose from the Pari Mahal of Lahore Fort on her east, Rani Jind Kaur, the Maharaja’s youngest wife, realised she had become a widow.

Jind instinctively picked up her 10-month-old son Duleep from the bed. Pressing him to her breast with one hand, she picked up a pankhi with the other. Her mind in turmoil, she started making rapid to-and-fro movements of the fan.

The Maharaja maintained a large harem of women—he had 20 wives, several dozen concubines and a troupe of 150 dance girls aged between 12 and 18. A few some of them had been taken to Pari Mahal to see their bedridden Sarkar early in the morning. Most of them decided to become sati by burning themselves on the Maharaja’s funeral pyre.

Jind had dreaded this moment ever since Maharaja Ranjit Singh had fallen ill. She knew, like the Maharaja’s other queens and concubines, she too would be expected to burn herself on his funeral pyre.

Jind walked silently back to her chamber in the Haveli named after her. She was hoping that the Maharaja would live on for a few more years, making it easy for her to take a decision. But, the loud cries from Pari Mahal told her she had to make a decision now.

Jind walked into her dressing chamber and looked into a mirror. She had a broad forehead, a firm face with high cheekbones, big, bright eyes, a sharp nose, a firm jaw and delicate lips that curled slightly upwards. At 20, she looked stunningly beautiful.

Jind took off her colourful kameez, crinoline and silk bonnet and threw them out of the jharoka of her haveli into the street below. One by one, she removed the pearls and ornaments she was wearing beneath them. By the time she came out of the dressing chamber dressed in plain white clothes with a black scarf pulled over the forehead, Jind had made up her mind—she will live for her son Duleep and lover Raja Lal Singh.

Her decision was to plunge the Khalsa Raj into turmoil a few years later.

**

Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s empire witnessed unprecedented bloodshot after his death. The first to die was his heir, Kharak Singh.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh

Soon after being anointed the Maharaja of Punjab, Kharak Singh embarked on an orgy of drinking and debauchery. On waking up, he would get high on laudanum and spend the rest of the day in a haze. In the evening, he’d get drunk in the company of his dance girls, whom he lavishly gifted for a night to his courtiers and visitors, some of whom went back not just with memories of a wild night but also the syphilis bacteria in their veins.

Before his death, Ranjit Singh was warned that his eldest son was not a worthy heir to the Sikh Empire spread from Peshawar in the west to the borders of China in the east, Amritsar in the south to Kashmir in the north. One of his physicians had jokingly remarked Kharak was capable of surpassing his father only in the consumption of opium.

But, the Lion of Lahore believed that Kharak was his only legitimate son—he doubted the parentage of other claimants like Sher Singh, whose mother, he believed, was barren and could, thus, not have given birth to his offspring. In spite of protests from his nobles, he had named Kharak Singh as his heir in the summer of 1839.

Within months of being anointed the King, Kharak Singh was confined to a haveli in Lahore a faction led by his own son Naunihal and the empire’s prime minister. In the winter of 1940, Kharak Singh died, probably after being poisoned by his enemies.

When Kharak Singh died, Kunwar Naunihal Singh was relieved that he would finally be able to claim the title of Maharaja. Swept by euphoria, he had feasted on laudanum the previous night and was a bit groggy when on the morning of November 5, 1840, he walked towards the funeral ground for his father’s last rites.

In the middle of the Bazaar, he heard somebody call out his name aloud. He turned around but nobody seemed to be looking for him. Then as he was giving shoulder to the king’s cortege, somebody tapped his head from behind. But, Naunihal Singh couldn’t see anybody nearby.

“Mian,” he told his friend Udham Singh, son of Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu while returning from the funeral, “this is a very queer day. Somebody slapped me on the shoulder but I couldn’t spot anyone. Then, I heard a strange voice whisper in my ear. Am I having too much opium these days?”

“Kunwar Sahab, I don’t think this is because of opium or alcohol. I have also seen ominious signs all day.”

Udham Singh continued, “Did you notice that when the pyre was lit, a tree fell down, bringing down with it people sitting on its branches. That’s a weird coincidence. I think there are some evil spirits around.”

“Mian, do you know what one of my father’s wives said before becoming Sati?”

“No, I noticed one of the queens said something to you before sitting on the pyre, but I couldn’t hear it.”

“She said: ‘A coward killed my husband. Now he will suffer.’”

“I think you should summon some priests and ask them to perform prayers to ward off evil,” Udham Singh replied.

Naunihal Singh was walking barefoot to the Fort after a long day in the open. He felt fear and thirst leap up through his throat. “I need some water,” he asked one of his servants.

“Kunwar Sahab, we have run out of holy water from the Ganga. And according to the custom, you can’t drink anything else today,” Dhyan Singh, who was walking besides him replied.

“Really! Have we run out of holy water? Oh God, this is such an evil day, Kunwar,” Udham Singh exclaimed.

“I feel faint. Come let’s stand for a few seconds under the shade of the Roshnai Gate,” Naunihal Singh grabbed his friend’s hand and walked towards the arched gate, which, suddenly collapsed, binging down tonnes of brickwork on the head of the heir to the throne and his superstitious friend.

“Kunwar’s back is broken,” shouted Dhyan Singh, who was just a few yards behind Naunihal Singh when the arched gateway collapsed. He quickly summoned a palanquin, asked five soldiers to put the injured Prince into it and rushed towards Naunihal Singh’s Haveli.

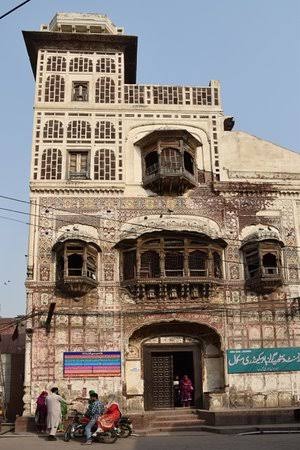

Haveli of Naunihal Singh, Lahore

For the next few hours, no word came out of the Haveli as the entire Lahore darbar waited outside with bated breath. His mother Chand Kaur kept beating the door, screaming, shouting and pleading that she be allowed inside. When its large gate finally creaked open the next day, Dhyan Singh announced in a feeble voice that Naunihal Singh was dead.

The physician who examined the Prince was to later say that he was alive after the accident but had later been hit in the head with a blunt object. Curiously, of the five men who had taken Naunihal to the haveli, three were killed and two disappeared mysteriously.

Naunihal Singh’s death remains one of the enduring mysteries of Lahore. Nobody can say with conviction if he had been killed by Dhyan Singh’s men or the arch that was to later become famous as Khooni Darwaza had fallen on his head on its own because its brickwork had come loose due to the constant firing of canons in honour of the dead Maharaja.

The state of Jammu and Kashmir was yet to be born. But, it had already claimed a few lives—a trend that was to later become its destiny.

Next: Kashmir for sale

End of