- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

A year on, rain, heat, winter chill and insults fail to deter India’s farmers

The winter chill is beginning to set in the national capital reminding farmers at Delhi’s borders that it has been a full 365 sunsets since they came to the doorsteps of the national capital, facing water cannons and lathicharge on the way, halted from making it to Lutyens’ Delhi, their chosen site to stage a protest against the three Farm Laws. A full 365 days and over 600 farmer...

The winter chill is beginning to set in the national capital reminding farmers at Delhi’s borders that it has been a full 365 sunsets since they came to the doorsteps of the national capital, facing water cannons and lathicharge on the way, halted from making it to Lutyens’ Delhi, their chosen site to stage a protest against the three Farm Laws.

A full 365 days and over 600 farmer deaths later, the Farm Laws are headed for repeal in the Winter Session of Parliament, which commences on Monday, with the Union Cabinet giving its consent and Prime Minister Narendra Modi apologising for “not being able to do enough to make farmers see reason in the merit of the farm laws”.

The farmers, meanwhile, are still at the borders waiting to see how things unfold, taking stock of what all that they have endured.

At Delhi’s North-West border with Haryana in Tikri, 67-year-old Randhir Singh Kunwar’s wizened face reflected no emotion, but grit as he waited for fellow protesters to join a meeting in a makeshift camp of bamboo canes and tarpaulin.

He, and many other farmers camping at Delhi’s borders, mark the anniversary of their sit-in agitation today. During the ongoing agitation, there were occasions when the stir appeared to be withering. And then suddenly, the protesters would gather themselves, and the agitation would surge. Through year of confrontation, dotted by 11 rounds of consultation with the Modi government, the farmers’ stir witnessed several twists and turns. The end, however, still doesn’t seem in sight.

“The Modi government has realised its mistake. But we’re not yet going back home,” said Kunwar, a farmer leader from Charkhi Dadri in Haryana.

So, why are the farmers still willing to endlessly brave the cold, the rain, the heat, the dust?

“Prices of diesel, petrol, pesticide, fertilisers–are all skyrocketing. The dole of Rs 6,000 handed per year (in three equal instalments under PM Kisan Yojana) hardly makes a difference. Neither does the token reduction in fuel prices help,” Kunwar added.

“The government is under pressure from big corporates. We demand that MSP be guaranteed by law and the Electricity (Amendment) Bill 2020 is scrapped,” added Kunwar.

Less than a kilometre from Kunwar’s makeshift abode, a small group assembled near a hut under the elevated Pandit Shree Ram Sharma station on the Green Line of the Delhi Metro in Bahadurgarh district of Haryana.

The nondescript hut is one of the many that has come up since November 26, 2020, under the shadows of the raised Green Line on Rohtak Road – ‘home’ to the protesting farmers and their families. Traffic was recently restored, but only on one side of the Rohtak Road.

Smog, dust, and blaring vehicles, all added to the chokehold National Capital Region (NCR) residents live under. Trying to ignore the distractions, the group had assembled to continue their meeting.

A frail septuagenarian farmer, Hukumchand Singh, lay on a charpoy nearby under a mosquito net, being nursed by his son.

“He was grievously injured in an accident in October. He has since recovered, but after being discharged from hospital, he insisted on staying put at the protest site. He says he’ll leave only after all our demands are accepted,” explained Gurnam Singh, a farmer from Bhikhi in Mansa district of Punjab.

And about 40 km away, at the other border of Singhu, farmer leader Gulzar Singh was also waiting for a meeting behind the makeshift stage where he had just delivered a speech.

The hurt and resolve

“The Modi government has tried every means possible to break our struggle. From using force to spreading canards–it used all possible ways to somehow evict us,” said the septuagenarian farmer-leader from Basant Kot village in Gurdaspur district of Punjab.

“They called us Khalistani, Pakistani… They accused us of collecting funds from anti-national elements abroad then claimed that we are harbouring criminals. We bore it all stoically. We did not lose hope,” he said.

After a short pause, he added, “We knew we were on the right path and that we were fighting for the betterment of the marginal peasants.”

Gulzar Singh has particularly come under sharp attacks, claimed his associates, being a state-level leader of the Left-affiliated All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS).

All this time, as groups of farmers squatted on highways at borders of the national capital with Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, senior leaders reached out to the states. A delegation from the umbrella organisation of protesters, Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM), visited West Bengal, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, among others. They explained their demands and political consequences.

The SKM leadership decided on the outreach after the violence during January 26 tractor parade in New Delhi. The protests turned violent as farmers clashed with the police and then some of them laid siege on the Red Fort.

The violence served as a setback to the movement and many began calling the protesters “anti-national, Khalistani, terrorists”.

The name-callings and brickbats that the fledgling SKM earned, however, failed to dent the morale of its constituents. Two days after the tractor parade violence, it seemed the Ghaziabad (Uttar Pradesh) administration would evict farmers squatting at the borders. The crowd had thinned after the Delhi protests in which one farmer lost life and several police personnel were injured.

Stories started floating that locals in areas where the farmers had been protesting were angry and demanding that they leave. When the protests had begun, many had written about how people were helping out the agitating farmers with supplies and even letting them use toilets and bathrooms.

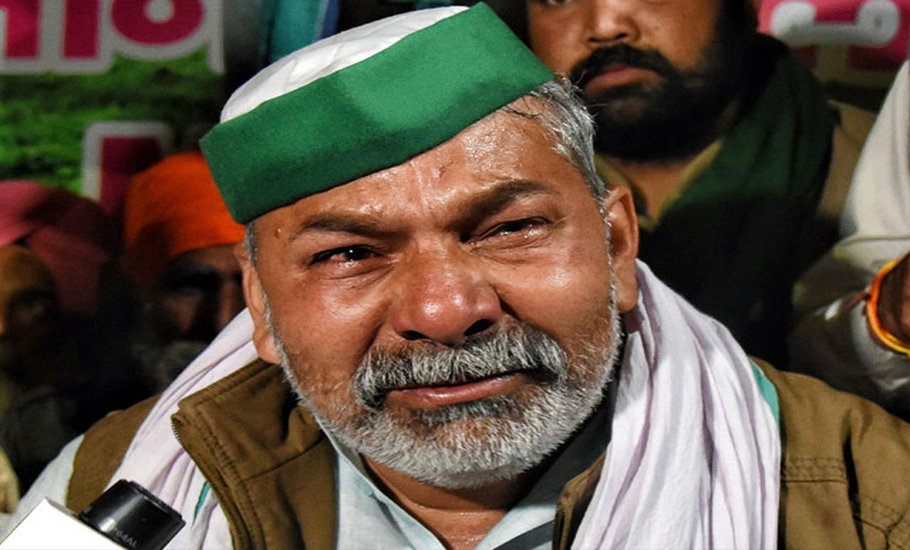

The twist came when Rakesh Tikait, the poster-boy of the agitation, broke into tears complaining of a slander campaign targeting farmers, especially those from Punjab. Soon after the sobbing face was beamed live on television, it went viral on social media. Hundreds of farmers who were returning home turned their vehicles towards Delhi.

Gagan Singh recalls that night. “I’d come to Ghazipur (Delhi-Uttar Pradesh) border late night on November 26 to join the struggle. For two months, I couldn’t go home. When I finally could, I was overwhelmed by the rousing reception that I got from villagers when I visited my family.”

“This is the beginning. There is more to be done,” he added. Gagan and his two brothers now take turns in joining the protests and tending to the crops.

“Life is not so easy for us here (at the protest site) amid the extreme weather conditions. Back home, we are working out our schedule according to the situation. Life has turned completely upside down,” he sighed before beaming again, saying, “Since Independence, this is the longest-ever peasants’ struggle in the country. We are fighting to better our future. We intend to offer a proper life to our kin.”

The farmers stayed put even when the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic swept the country with over 4,000 deaths and 4,00,000 cases getting reported per day for several consecutive days. The Bharatiya Kisan Union issued an appeal to farmers to halt the agitation, but the protesters remained undeterred.

The impact

The tremors of this agitation have been felt the strongest in Haryana, Punjab, and parts of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Toll gates on highways were thrown open to traffic, BJP leaders were stopped from attending any event, and protesters laid siege to administrative offices.

“Narendra Modi has seen the writing on the wall. The results of the recently held byelections reflected the fact that days of tyranny of the majority are over. He has seen how his leaders are cornered in Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Haryana. We’ve borne all name-callings while we spent days and nights in sweltering summers, harsh monsoon, and chilling winters… with dust and smoke to be breathed in,” said Gulzar Singh.

All this time, the farmers’ movement had drawn support from various quarters, mostly workers’ unions.

Meet Santokh Singh Sandhu from Jalandhar. The 62-year-old joined two other volunteers at Singhu Border to keep track of expenses.

The former government employee joined the farmers one year back and has hardly visited his wife, a son and daughter back home.

“I took retirement from service nine years ago to work for (the Left- affiliated) All-India Kisan Mazdoor Sabha. I have been here [Singhu Border] for almost a year where I and two others manage finances, especially cash expenses,” he said.

“I hardly get time to visit home. But this time I had to–after contracting dengue–and have just returned after recovery,” added Sandhu.

They are adapting to a new life. And in the words of Gurnam Singh: “The highway is our home. We bear the pain, the ignominy, humiliation like the stoic. It’s all for a better tomorrow… A new day.”