- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

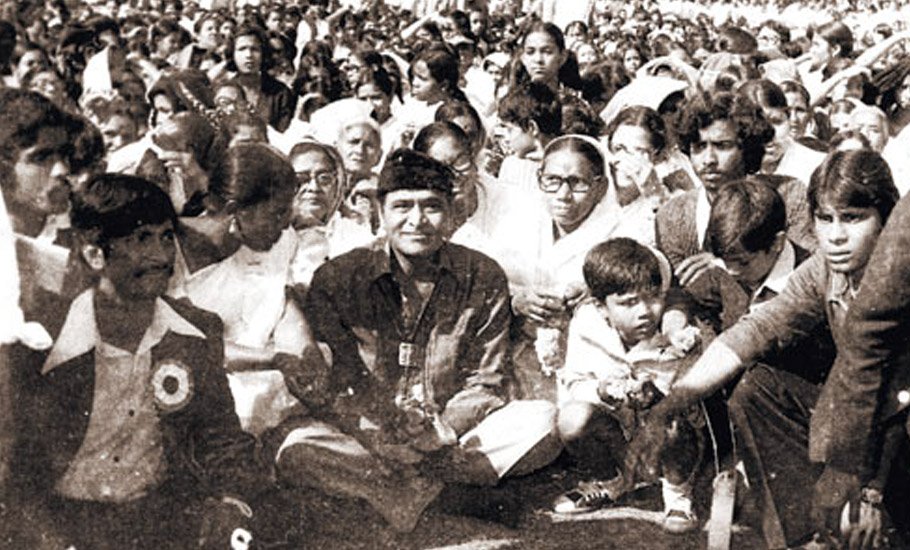

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Assam is stuck in time warp over identity and it's not going to get over soon

When thousands of youths thronged the streets in Assam earlier this year carrying bamboo torches, chanting ah oi aah, ulai aah (come out, come out all), there was a sense of deja vu for septuagenarian Ramen Mahanta. The youth were opposing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Assam on January 23 for failing to safeguard the Assamese identity. Mahanta, a retired professor now settled...

When thousands of youths thronged the streets in Assam earlier this year carrying bamboo torches, chanting ah oi aah, ulai aah (come out, come out all), there was a sense of deja vu for septuagenarian Ramen Mahanta.

The youth were opposing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Assam on January 23 for failing to safeguard the Assamese identity.

Mahanta, a retired professor now settled in Tezpur, remembered that he had himself taken part in several such protests decades ago.

“We waved black flags on a February day in 1983 at the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi as her helicopter touched down at the playground of Netaji Vidyapeeth at Maligaon (in Guwahati),” he recalls.

It was also an election season and the state was fuming in rage over alleged inclusion of foreigners in the electoral roll.

Several political parties including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Janata Party had boycotted the polls questioning their legality.

Since then gallons of water have flowed down the mighty Brahmaputra but Assam appears to be frozen in a time warp.

Over three decades later, after being ruled by seven governments led by three different parties, the state continues to be mired in identity politics.

The Assam Movement

It all started in 1979 when the state’s first non-Congress chief minister Golap Borbora of the Janata Party ordered a police officer to detect any foreigners on the electoral roll of Mangaldoi parliamentary constituency. A by-election in the constituency was necessitated following the demise of Lok Sabha MP Hiralal Patowary.

The police probe detected 47,658 ‘foreigners’ in the list, triggering a statewide movement for detection and deportation of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

This triggered a mass movement, known as the Assam movement, against the Centre. After six years of agitation, the protagonist of the movement, the All Assam Students Union (AASU) signed a peace accord with the Union government in 1985.

From the throes of the agitation, the political outfit Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), an offspring of the AASU, came into being.

The party ruled the state for two intermittent terms from 1985-90 and 1996-2001, but was not able to address the core issue on which it was formed—detection and deportation of foreigners to safeguard the identity of indigenous people of Assam.

The unresolved identity issue vis-a-vis the so-called influx of foreigners was ultimately reduced to a political sling to catapult into the saddle of power.

In the latest case, the BJP used the issue to ride to power in 2016, promising an updated National Register of Citizens (NRC) to disenfranchise ‘foreigners’.

However, it quickly shelved the exercise after the final list, prepared after painstaking scrutiny, left out over 19 lakh people. The number turned out to be much less than the imaginary figures of foreigners being reeled out over the years to raise the bogey of infiltrators.

More importantly for the BJP, a large chunk of those left out were Hindu Bengalis and tribals, whose exclusion punched a hole in the BJP’s anti-foreigners narrative, built around Bengali-speaking Muslim migrants.

To impose its own brand of politics in Assam, the BJP government at the Centre enacted the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in 2019, triggering another youth-led protest for the safeguarding of Assamese identity.

Newborn from the same cradle

This time the protest gave birth to another AASU offshoot, the Asom Jatiya Parishad (AJP).

The entry of the debutant regional political party ahead of the 2021 Assam assembly elections naturally led to compression of the event with the emergence of the AGP 35 years ago over the same issue.

Just as the AGP had promised then, the AJP general secretary Jagdish Bhuyan tells The Federal that it was the only credible regional party that could protect and promote Assamese culture and identity.

The party hopes to repeat the AGP’s maiden electoral performance based on the same old-issues of identity, culture and language.

The issue though continues to remain as emotive and complex as it was 35 years ago—not many trust political leaderships anymore to address it though.

A cause betrayed?

Pradip Kumar Bhagawati, a retired bureaucrat from Assam recalled how the AGP was formed out of a massive outpour of sympathy and this rode them to power in 1985.

“People looked at the AGP leaders as saviours and took it as their personal battle, and helped the candidates with resources. People came out to campaign for them on their own,” says Bhagawati.

The subsequent AGP governments headed by Prafulla Kumar Mahanta proved to be a big letdown, leading to its political decimation.

From the champion of the Assamese cause and regional aspiration, the AGP today is an insignificant partner in the Assam government led by ultra-nationalist BJP.

“The AGP leadership had completely ignored the issues—identity and constitutional safeguard of the Assamese people, based on which the party had campaigned and come into power. The people of our generation took it as a betrayal by the AGP, and it’s least likely that they will trust a new political party formed out of AASU again,” says 78-year-old KR Nath, a retired government official, who was even detained during the peak of the anti-foreigner agitation for being an AASU sympathiser.

There are several others from the generation that witnessed and participated in the Assam agitation of the ‘80s who agree with Nath.

It is this AGP legacy that will continue to haunt the AJP as it forays into electoral politics.

Another challenge for the AJP electorally is the proliferation of identity politics in the state in the past decades.

“During its time, the AGP was the only claimant for the votes in the name of pan-Assamese identity. But today many regional parties, representing various ethnic communities have sprouted, slicing the identity pie,” says Bhagawati.

To surmount the challenge, the AJP is banking on its youth power.

“There are lakhs of both young and first-time voters, who have never seen the Assam agitation, but have pledged support to the AJP. The backtracking by the BJP on its crucial promises like deportation of illegal immigrants and on implementation of Clause 6 of Assam Accord has made people realise that a strong regional political party is needed to safeguard Assam’s interest,” said Gargee Kashyap, convenor of the regional party’s youth wing.

Clause 6 of the historic accord calls for constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards to protect, preserve and promote the cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people.

In February last year, a state government-appointed committee had submitted its recommendations for implementation of the clause, a key provision of the Accord that has remained contentious for decades. The BJP government did not make the report public, ostensibly to avoid stirring up another hornet’s nest.

The irony in the BJP’s perceived move and the emergence of the AJP as the new advocate for the cause define the course of politics over Assamese identity.

Every party rakes up the issue to reap political benefits and then when it gets too hot to handle, leaving it to a new torchbearer to raise the clamour.

The process ends up only in further fragmenting the larger Assamese society.